-

[1990-04-05-Pioneer] Ryuma Go vs Masaji Aoyagi

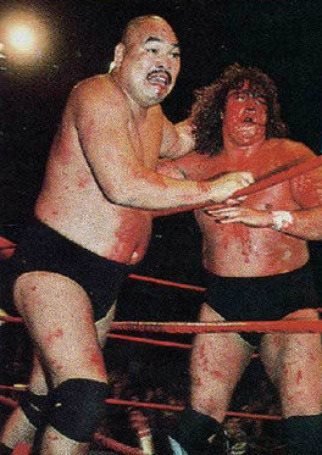

I will be touching on this match in the next episode of my podcast, so consider this clearup a preview. The man in question is Animal Hamaguchi, and Masayuki Sato's Weekly Pro writeup of the match made it very clear that this adlib salvaged the show. The crowd was calling for the match to be extended, and by 1990 puro had entered the period where you really did not want to piss off a Korakuen crowd too much, especially if you were as small-scale as Pioneer Senshi. When it's clear that the men can't continue to perform, Hamaguchi asks the audience "are you all satisfied with this?" All that said, you really aren't getting the complete experience of the match if you haven't seen the first pic of the Weekly Pro writeup.

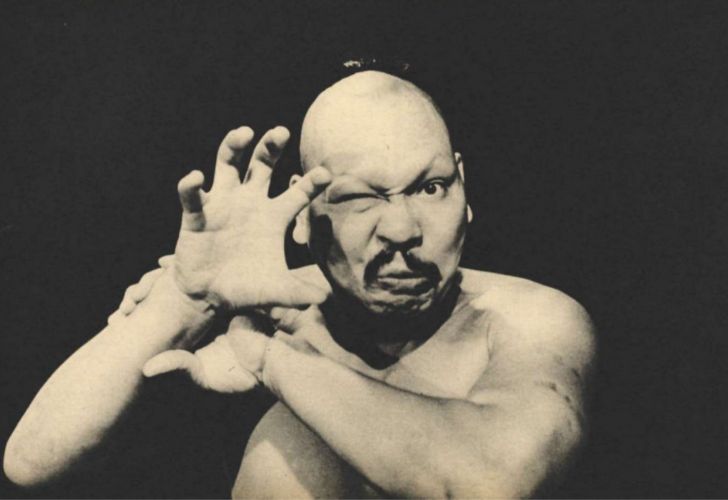

- Killer Khan

-

Motoyuki Kitazawa

I have substantially expanded this profile with information about Kitazawa's early life, details on his practical contributions to New Japan and the UWF, and some important corrections. Mighty Inoue's passing and the lackluster obituaries he received in the West have made it clear that my profiles here must stand as the definitive English obituaries of these legends. All of my profiles are living documents, but I have a responsibility to make them the best that I can make them while their subjects are still living.

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

RIP Mighty Inoue.

-

From Milo To Misawa: The Men, Myths, and Legends of Classic Puroresu

Rest assured that I have no intent of leaving this as a one-off. I can't promise a quick turnaround time, because I am not going to simply regurgitate my PWO corpus for material. But I have various ideas for the future, and some of them were hinted at in the pilot! Episode 2 is going to be a Ryuma Go biography with a lot of new material. I want to cover Inoki vs. Kobayashi after that. These will be warmups for my first multi-parter: a three-part saga on Kintaro Oki and the history of South Korean wrestling. But as they say, card subject to change.

-

WON HOF 2024

Ah, I haven't listened to that. I knew of his importance in improving the quality of Gong's coverage. Before he joined, they were just making up shit like "Mil Máscaras is a disfigured tailor named Miguel Morales". But there is absolutely merit in the role you describe. I admit I haven't subscribed to the Observer in years, but when I take the plunge next time I'll check that show out.

-

WON HOF 2024

It's neat that Yoshizawa got into the non-performer nominations, but I would give the nod to Kosuke Takeuchi before him. Yoshizawa was the reporter who really helped get Gong going, but Takeuchi ~was~ Gong. But the whole history of puro journalism is not well-known to voters. I'd put Tarzan in the hall myself, for pimping shoot-style (including pretty much writing Sayama's Kayfabe) and then acting as a creative consultant to All Japan.

-

From Milo To Misawa: The Men, Myths, and Legends of Classic Puroresu

My solo podcast on puroresu history has released its pilot episode. It's an hour-long look at the Idol Showdown between Jumbo Tsuruta and Mil Mascaras, but it's not a standard review of the match. I go deep into the historical context of the match, building the story up through the groundbreaking use of entrance music for Mascaras in early 1977. I take a look at the fan culture of the time, through the perspective of a fan club chairman whose life was shaped by Mascaras. I uncover the reason why the Jumbo-Mascaras match was booked. I take an educational approach to the match discussion, hoping to give modern fans a guide to appreciate the more traditional craftsmanship at play. But there's also a deep discussion of Jumbo's early issues with the core puroresu fandom, which ranged from the style and structure of his matches to his broader demeanor. And yes, I also talk about Mascaras. If you have enjoyed any of my writing on the board, I urge you to give this a shot. There's so much that I haven't shared before. FM2M001 - Night of the Idols | From Milo To Misawa

-

The Big Puroresu Profile Index

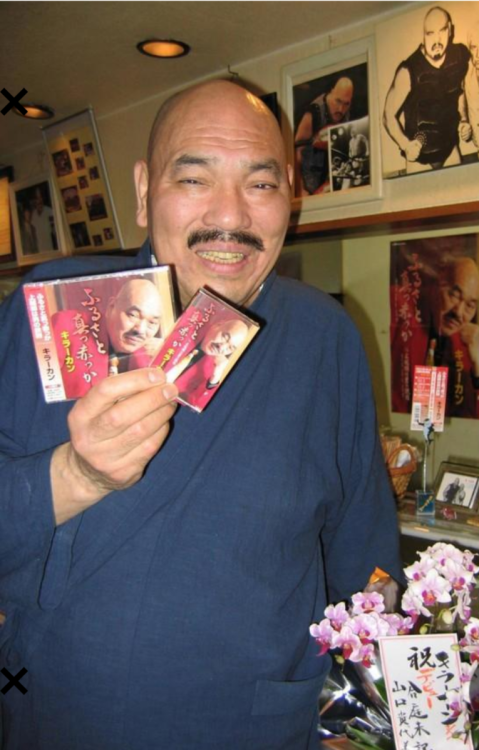

UPDATES, APRIL-MAY 2024 I outdid myself again with my fourth Deluxe Profile: 19,000 words about the late Killer Khan. Killer Khan (Wrestler, JWA/NJPW/AJPW[Japan Pro]) [DELUXE PROFILE #4] Tamio Takeshita (Wrestler/Referee, JWA/IWE) [REWRITE] Umeyuki Kiyomigawa (Wrestler/Trainer/Referee/Commentator, AJPWA/Kimura's Kokusai/IWE/AJW) Yukari Lynch (Wrestler, AJW)

- Tamio Takeshita

-

Umeyuki Kiyomigawa

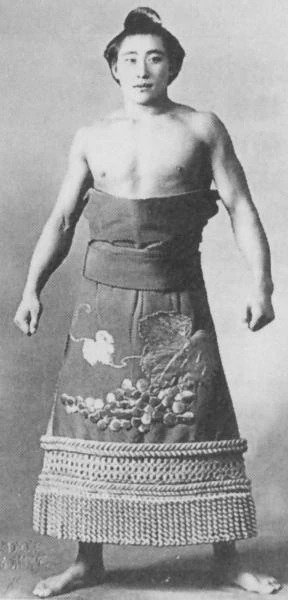

Umeyuki Kiyomigawa (清美川梅之) Profession: Wrestler, Trainer, Referee, Commentator (Color) Real name: Umenosuke Sato (佐藤梅之助) [birth], Umenosuke Ohashi (大橋梅之助) [marriage] Professional names: Umeyuki Kiyomigawa, Kiyomigawa, Togo Tani, Togo Shikuma Life: 1/5/1917-10/13/1980 Born: Jumonji (now Yokote), Akita, Japan Career: 1953-1979 Height/Weight: 183cm/94kg (6’0”/207lbs.) Signature moves: unknown Promotions: All Japan Pro Wrestling Association, Kokusai Pro Wrestling (Kimura), International Wrestling Enterprise, All Japan Womens’ Pro-Wrestling (as trainer) Titles: Latin American Tag Team [Kokusai (Kimura)] (1x, w/Masahiko Kimura), NWA Tri-State Tag Team [NWA Tri-State] (2x, w/Chati Yokouchi) Umeyuki Kiyomigawa was a puroresu pioneer who left Japan before the JWA cemented its monopoly. After a lengthy career as a journeyman in Europe and the States, he gave back to Japan as a talent booker for the IWE, and then as a joshi coach. [Content warning: This profile covers the murder of a child.] Umenosuke Sato joined the Isegahama sumo stable at 16 and debuted in 1934. He originally wrestled as Satsumagawa before a switch to Umeyuki Kiyomigawa in spring 1937. He was promoted to the juryo division the following year, and then reached the top division, makuuchi, in the spring tournament of 1940. The highlight of his career came two years later, when Kiyomigawa pulled an upset against the legendary yokozuna Futabayama and broke a 22-win streak. After a poor final performance in the only tournament of 1946, in which one of his losses came against Rikidozan, he retired. As he stated, his reason was to take over the ryotei restaurant of a patron whose adopted daughter he had married, and whose surname, Ohashi, he had taken as his own. That marriage did not last. Umenosuke moved back to his native Akita prefecture around 1948 to run a sawmill. After that closed, he moved to Osaka and found work at Otani Steelworks, whose sumo club he wrestled for in the early fifties. On July 18, 1953, Kiyomigawa took part in Osaka’s first puroresu show, an outgrowth of the Kansai region’s juken (judo vs. boxing) revival. A charity event for victims of the Kitakyushu flood, this show at the Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium was headlined by a judo vs. sumo match, in which Kiyomigawa lost to judoka turned pro wrestler Toshio Yamaguchi. Less than three weeks after the JWA’s formation in Tokyo, this show led to the formation of puroresu’s second promotion. A translated Mainichi Shimbun article on the show found its way to a GI who saw an opportunity to “manage” his commanding officer in a wrestling match against Yamaguchi. When local yakuza boss Shojiro Matsuyama caught wind of the offer, which Yamaguchi had declined, he made a request to Mainichi to hold the show, and the All Japan Pro Wrestling Association was born. Alongside former Dewanoumi rikishi and Otani club teammate Hideyuki Nagasawa, Kiyomigawa became a charter member of Yamaguchi’s new promotion. He wrestled on the AJPWA’s pair of kickoff shows on December 8 and 9. Another pair of shows, sponsored by the Manaslu climbing team, took place on February 6 and 7, and the first of these shows was given puroresu’s first television broadcast by NHK Osaka. When the JWA began its first tour shortly after, Kiyomigawa, Yamaguchi, and Nagasawa took part. Umeyuki opened the JWA’s first show, wrestling Harold Toki to a time-limit draw in the Kuramae Kokugikan. The AJPWA held its first tour that spring, promoted as a tournament between Japan and the American military. Kiyomigawa remained with the Association for most of its life. On the following January’s joint show with the JWA, Kiyomigawa lost his match, a tag with Nagasawa against Kokichi Endo & Yusuf Turk. Nine months later, Kiyomigawa was absent for All Japan’s October 7 show in Osaka. He had transferred to Masahiko Kimura's Kokusai Pro Wrestling, which held its first show in Osaka that December. Kimura's Kokusai was quickly disgraced when its “star” foreigner, discharged American serviceman Gorgeous Mac, was busted for jewel theft at Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel. On May 15, 1956, Kiyomigawa teamed up with Kimura and defeated Raul Romero & Yaqui Rocha for the fictitious Latin American Tag Team titles. (Kokusai was fifteen years ahead of the punch in bringing luchadors to Japan.) Two months later, on July 9, Kokusai held a joint show in Osaka with Toa Pro Wrestling, a small Zainichi Korean promotion that ran the market after All Japan folded. After Kiyomigawa won his match against Kuroda (we only have the surname), he and Kimura traveled to Mexico. There are records of a month’s worth of shows across August and September. Kokusai’s remnants formed a new promotion, Asia Pro, that September. Kiyomigawa was listed in their official directories, but never returned to work a date for them (not that any show records survive). One of Asia Pro’s wrestlers, Shiro Tsukikage, later remarked that Kiyomigawa was unprepared to return to Japan due to “complicated circumstances”. Such circumstances soon became tragic. Kiyomigawa had a son with his ex-wife. Now twelve, the boy went missing on April 2, 1957, and his mother received a ransom letter two days later. As it turned out, this letter had been a cruel joke. The child was already dead. He had been lured from a public bathhouse to the home of a 26-year-old man who happened to be the son of a noted go player. When he refused to undress, the child was beaten to death and his body was dismembered, partially buried in the murderer’s yard and partially preserved in formaldehyde. Kiyomigawa learned the news from a friend. There are no show records to trace the man until the early sixties. The only lead I have is a testimony from Mighty Inoue, which suggests that Kiyomigawa was in Brazil at some point in the following five years. As Inoue recalled, Kiyomigawa told him that he first met his future tag partner, Shinichi “Chati” Yokouchi, in Brazil. Yokouchi was twenty years his junior, and a failed businessman who tried to get training from him. After Kiyomigawa turned him down, Yokouchi was purportedly trained by Antonino Rocca, and found his own way to Europe in the early sixties. Kiyomigawa (center) in Alphaville. Kiyomigawa wrestled as Togo Tani in England for Australian promoter Paul Lincoln. A single show record on WrestlingData.com claims that Togo Tani, as well as Yokouchi, worked for Don Robinson in November 1961. British wrestling history site Wrestling Heritage claims that Lincoln himself had wrestled as Togo Tani at the start of the decade, whereas Kiyomigawa did not adopt the ring name until 1963. Less ambiguous are show records in Spain and France the following year, where Kiyomigawa wrestled under that old sumo name. At the absolute latest, it was by 1963 that he started teaming up with Yokouchi. In 1965, Kiyomigawa got one of the most interesting cinematic credits in all of puroresu: a bit part as a bouncer in Godard’s Alphaville. Two months after its release, he was in Germany, working his first known tournament for Gustl Kaiser. Kiyomigawa was approached by Klaus Kauroff, a truck driver and former amateur boxer, but turned him down. The following year, when Kiyomigawa won his second Hannover tournament, he agreed to take Kauroff under his wing. Kiyomigawa (left) and Yokouchi gang up on Mike Marino, in a 1966 Royal Albert Hall match. Kiyomigawa came to America in spring 1967. As Togo Shikuma, he worked in the Oklahoma territory for six months. He and Yokouchi must have been a well-honed act by then; the Wrestling Heritage bio alludes to a particularly dastardly heel performance at the Royal Albert Hall the previous year, against Mike Marino & Steve Viedor. The pan-shaped state rewarded them with the NWA Tri-State Tag Team title, which they won in Little Rock from Jack Brisco & Gorgeous George Jr. on May 9. While different markets in the territory billed different teams as champions, the duo held on to the belts in the canonical lineage until September, when they lost them to Danny Hodge & Skandor Akbar. Shikuma and Yokouchi won the titles back in a rematch one week later but lost them to Hodge & Akbar in early October. Apparently, that was when Kiyomigawa left Oklahoma. He never worked with Yokouchi again, and there was evidently no love lost. (Years later, he told Mighty Inoue that Yokouchi had moved to Brazil all those years before to evade a murder charge.) Kiyomigawa wrote to JWA wrestler-executive Michiaki Yoshimura, a fellow alumnus of Yamaguchi’s All Japan, to request a new Japanese tag partner. He did not get one, but somehow, he got enough money for a plane ticket back to Europe. Etsuji Koizumi speculated that this was due to the generosity of Giant Baba, who Kiyomigawa may have encountered in Los Angeles at the end of the year.[1] Kiyomigawa won a second Hannover tournament in 1969. Far more important to his legacy, though, was a connection he made that spring. In May, Kokusai Puroresu/International Wrestling Enterprise promoter Isao Yoshiwara came to Paris as Toyonobori & Strong Kobayashi won the new IWA World Tag Team titles. He hired Kiyomigawa as a talent booker, taking the place of Leeds promoter George de Relwyskow. This later cost the IWE a parallel relationship with Yokouchi, who briefly booked and wrestled for the promotion in the late stretch of the year. But it gave them a fresh crop of European talent, and it gave the young Andre the Giant his first work outside Europe. Kiyomigawa himself wrestled a single tour for Kokusai in 1970, and got its talent work in Europe, for the likes of Edmund Schober in Germany and Etienne Siry in France. He dropped back in on the IWE for their first tour of 1973, working as a referee and color commentator. He won the Hannover tournament for a third and final time that year and returned to Japan in the late year for “rest and business”. On December 10, he appeared backstage at New Japan’s show at the Kuramae Kokugikan, where Antonio Inoki beat Johnny Powers for the NWF Heavyweight title. It is likely that Kiyomigawa was in on the secret negotiations to bring Kokusai’s disgruntled ace, Strong Kobayashi, to NJPW for a match. Like Kobayashi, he wrestled on the IWE’s first tour of the next year, and then cut ties. On March 19, 1974, Kiyomigawa was the impartial referee for Inoki and Kobayashi’s first match. He had wanted a job with New Japan, but Inoki had asked Hisashi Shinma not to hire any more performers. So Umenosuke only got the single appearance, for which he was paid ¥300,000. That June, Kiyomigawa joined All Japan Women's Pro Wrestling as a referee, coach, and commentator. He worked for the Matsunagas for four years, and trained Mach Fumiake, the Beauty Pair, and more. (According to Ryuma Go, who Umeyuki brought to France in 1973, Kiyomigawa had already been training French women to wrestle.) These four years are Umenosuke’s greatest contribution to the business, and native puroresu journalism has sadly underserved them. As the decade reached its last year, he left the company to help form a competing joshi promotion. New World Women's Pro-Wrestling folded after a month. On October 13, 1980, Kiyomigawa suffered a fatal stroke in Shizuoka. FOOTNOTES

-

RIP Killer Khan

It took four and a half months, and 19,000 words, but I did it.

-

Killer Khan

EPILOGUE [Content warning: this section mentions a 2014 suicide attempt.] Ozawa first went back to Florida, but had no intent to remain. He knew that it would be much easier to make a living outside of wrestling in Japan, even if Cindy was not going to follow him back. He claimed that he left most of his money with his family, as he took a flight back home. He stayed at his brother’s Shinjuku apartment; the book doesn't specify which brother, but it was presumably Masaru. During this period, Masashi claimed that he seriously contemplated murdering Choshu, and had gone so far as to purchase a suitable kitchen knife. For the sake of his children, he did not go through with it. Soon afterward, Ozawa got a tip. A friend of a friend ran a snack bar near a Nagano onsen. Ozawa teamed up with them and gave the establishment his ring name. Customers started “pouring in”, and “it was right around the time that karaoke was becoming popular.” Ozawa had found the calling of his new life, but he was not to remain in Nagano. Masashi had left all the money he had earned in the States with Cindy, so he borrowed funds from friends to open his own restaurant in Tokyo. It was the bubble period, and he struggled to find a space that would accommodate a full restaurant. He settled on a small space in the Shinjuku underground, near Nakai Station. With karaoke, alcohol, and the part-time services of a few office ladies, Snack Khan-chan was born in 1989. A snack bar only gave Ozawa a small kitchen to work with, but he had no interest in serving dry foods. He served fried tofu and pickled seasonal vegetables. In the winter, he cooked “oden-like dishes”, and stuffed cucumbers with chikuwa and cheese. (It is worth noting that the businesses under the Khan banner changed his name slightly, as the long vowel was deleted from カーン to read simply カン. Ozawa claimed that this because it was simply the correct reading: a matter of pronunciation, not trademark.) Within the first year of the bar’s life, Ozawa met his most famous customer. A regular who worked in the automotive industry brought a friend in his mid-twenties, who wanted something more substantial to eat. Ozawa had made himself a plate of curry, but he gave it to the new guy as one of the women in his staff took him aside. As she explained to her boss, a man with evidently poor knowledge of pop music, he had just given his dinner to singer-songwriter Yutaka Ozaki. Ozaki loved the dish and came back three nights a week for it; fortunately for him, about a year after the snack bar opened, Ozawa took over an izakaya in nearby Nishi. One night, he even sang his own song, “I Love You”, with another customer. As Ozawa told the story, that was on the same night that the only photograph of the two was taken. In the early nineties, after a reunion at the bar with Genichiro Tenryu, Ozawa received an offer to return to the ring for SWS. In The Phantom of Mongolia, Ozawa wrote that the offer was better than he had expected. But he was out of shape, and even if he had never officially retired, he felt that a return in his current condition would disgrace him. Two years later, Ozawa elaborated on the matter in an interview. Tenryu had piled up ¥80 million in front of him, but the kicker was that three quarters of it would have gone to purchase Masashi an apartment. He also claimed that he had feared a McMahon lawsuit if he were to quit while under contract. On April 25, 1992, eight days after his final visit, Otaka was found unconscious and naked in a Tokyo alley: dismissed from the hospital, he died several hours later. The Khan-chan Curry lived on with Ozaki’s fans. The curry substituted vegetable and apple juices for water in the roux, and interviews in 2007 and 2022 also cited cocoa and garlic as ingredients. The potatoes were mostly cooked separately; he preferred crunch to crumble. There were other foods, of course. The restaurants with Khan’s name represented the standard izakaya cuisine, such as gyoza and various fried and grilled meats. His old lives, those of the dohyo and the ring, were represented by a miso chanko. Ozawa nicked an oyster recipe from noted rakugo comedian Danshi Tatekawa (VII). Danshi had been friends with Ozawa since the seventies and had served his oysters to Ozawa and Cindy during annual New Year's visits in the eighties. At one point, Ozawa served a kimchi hot pot based on a culinary experiment in the New Japan dojo. Ozawa made small appearances in film, television, and direct-to-video fare. In 1994, he even appeared in an American production. Billed as Killer Khan, Ozawa played a bit part in the martial-arts kiddo flick 3 Ninjas Kick Back. As a baddie bodyguard, he got a brief four-on-one fight scene some seventy-five minutes into the picture. He started strong, powerbombing the eight-year-old Tum Tum into his brothers, but the Japanese girl of the group used matador tactics to win, calling him a baka and goading him to run headfirst into the wall of the cave. (As a personal aside, this was how I first saw Killer Khan, some fifteen years before I became a puroresu fan, in my foster father’s VHS collection.) Ozawa with copies of his debut single. Shortly before Ozawa left for Mexico in 1978, Danshi Tatekawa had introduced him to Michiya Mihashi, one of the first major stars of enka music. Masashi had loved singing since childhood, and apparently, Mihashi thought he had potential. The online articles I have found imply that Ozawa received lessons before Mihashi’s death in 1996. The new century saw him stretch out into this other lifelong passion. He released his debut single in April 2005 and recorded two more over the next fifteen years. Masashi gave small concerts at nursing homes, where he drew from the Mihashi songbook to supplement the original material he had commissioned. He even sang on television, appearing on Roy Shirakawa’s enka programs for Tochigi TV. Ozawa sings a short set on June 21, 2021. This was for Japan's celebration of the annual Fête de la Musique/World Music Day festival. In the early 2010s, there were three Khan-chan restaurants in Tokyo: the Kabukicho izakaya, a standing bar elsewhere in Shinjuku, and another joint near Ayase Station. While there were three Khan-chans, though, there was only one Khan, and Ozawa wrote that this was why he pared things down to the Kabukicho location. Then, he moved it back to Nishi. In early 2014, Ozawa slipped in the snow and severely injured his spine. The doctor claimed that a life bound to a wheelchair was virtually a certainty. In a moment of despair, Ozawa intended to jump from his hospital window, but was too weak to open or break it. He slowly regained his strength and returned to work in time for a reunion with Hulk Hogan, who had tagged along for a WWE tour. When Hogan asked Ozawa why he had retired, all that he told him was that “there were a lot of reasons.” Ozawa recovered enough to commute by bicycle. The izakaya moved back to Kabukicho in 2015, on the third floor of a building full of host clubs. It was a poor fit. In his own words, the district had “lost momentum when the Yamaguchigumi split and started fighting.” In September 2016, Ozawa opened his ninth establishment, the latest Izakaya Khan-chan, near Shin-Okubo Station. It was on the ground floor, as any pub should be, and it was the restaurant he had when The Phantom of Mongolia was written. Though the rent was high, it was a busy spot, and Ozawa took pride in his tasty, affordable menu. In 2019, a plate of Khan-chan Curry over koshihikari rice cost ¥800. The most expensive food was the ¥2800 chanko, but this came in a pot enough for three. Around this time, Masashi became a grandfather. In a 2020 interview to promote his third and final single, Ozawa said that he had never moved back to the States due to health insurance, but stated his intent to retire from the restaurant business at 80, and move back to spend his last days with his family. In October 2020, on his way to work, Ozawa collided with a woman distracted by her phone, sending her to the hospital. Eyewitness accounts of his wobbly rides to work make it clear that his continued method of commute had been ill-advised. A visit to the police station was reported in December, and though charges were dropped, Ozawa was harassed for the incident. A few months after the hit-and-run, the Kabukicho restaurant was closed. He took a couple years to return to the business. In March 2022, he disclosed on YouTube that he was battling sigmoid colon cancer. Like other Japanese wrestlers of his generation, Ozawa started a YouTube channel to vlog about his life and career, though it has since been taken down. In March 2023, he opened his tenth joint, the Khan-chan Ninjo Tavern. A Jisin article the following month showed him as a rejuvenated man, whose mental health had recovered from the cycling incident. As the year drew to a close, though, he was heard complaining of chills and neck pain. On December 29, Ozawa was three hours late to work, and visibly fatigued. As he sat at the counter to serve customers, he lost consciousness. While resuscitated at the tavern, he died that night at the hospital. The cause was a ruptured artery. One week later, on January 4, the family held the funeral in Shinjuku; it was Cindy’s first trip to Japan since the Japan Pro days. Five days after that, the tavern opened back up in a “farewell party”. They did nineteen days of business, with Ozawa’s portrait placed at the spot where he had last sat. Customers and old colleagues came for curry and oysters, as the incense mingled with the scents of the menu. ------------ This biography is dedicated to the family, but especially the grandchildren, of Masashi Ozawa. I can never truly tell them who he was. That is not my place to tell. But I can tell them what he did.

-

Killer Khan

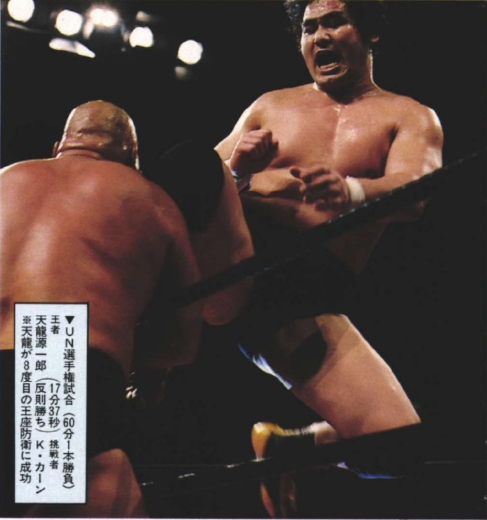

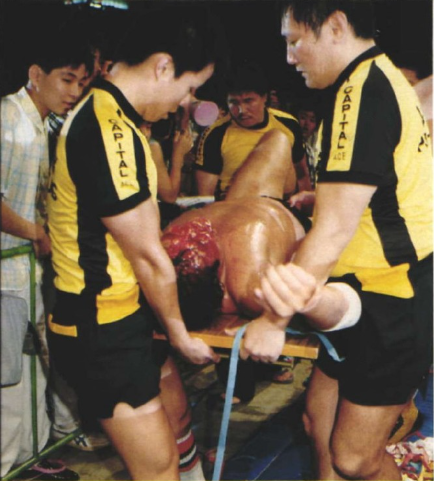

PART FOUR: THE LATE CAMPAIGNS (1985-1987) All Japan, and Japan Pro, began 1985 with a three-night run at Korakuen Hall. On the first night, January 2, Ozawa went to the All Japan waiting rooms to greet Baba, who was glad that he had finally come to work with him. Khan’s debut was against Gypsy Joe, who five years earlier had been the top foreign heel of the IWE; he squashed him in 1:14. Tag matches against Baba built up to a singles match, which Khan lost, at Japan Pro’s so-called “1st Anniversary” show on February 21. But from the start, Khan also took part in the volatile All Japan vs. Japan Pro tags and six-man tags which best defined much of the year. This first tour also saw Ozawa get his revenge on Gran Hamada, who had politicked in the UWA to get a Khan-Andre match cancelled in 1981. On January 22, at a house show in Otsu, he told Hamada to come to a certain restroom after his match. After Hamada finished his day’s work, a tag with Mighty Inoue, the two came back to wash up. Ozawa punched Hamada several times, swelling his face, while Inoue just stood there. Ozawa received no reprimand. (Hamada left All Japan in June.) Ozawa later wrote that he did not share his coworkers’ air of superiority towards All Japan, which Choshu had famously articulated the previous year: “we rock, they waltz”. In fact, he was the most enthusiastic one of the bunch to be working with AJPW. However, that did not mean that he respected everyone on the ‘other side’. Masashi held Jumbo Tsuruta in dim regard, as he believed that he was mostly good “at making himself look good”. He had been offended by a quote in a wrestling magazine where Tsuruta chalked Killer Khan’s overseas success to his ugly mug. Ozawa had more respect for Genichiro Tenryu, who he had bumped into a couple times during his first American run; he was certain that he was not alone in holding Tenryu in higher esteem. Khan’s first big singles program was for Tenryu’s NWA United National title, and the two had a very good match over it on April 12. It is also notable that Khan played a part in the Japanese debut of the Road Warriors. In 1984, three years after Tokyo 12 Channel had cut ties with the IWE, the renamed TV Tokyo had dipped back into wrestling with Sakae no Puroresu (“World Pro Wrestling”), a Saturday morning show which licensed overseas footage to compete with talk shows. They needed stars to build around, and under the advice of Gong reporter Koichi Yoshizawa, Sakae no Puroresu chose the Warriors. Now, as Sakae wound down its first run with the fiscal year,[1] Hawk and Animal made their Japanese debuts. This context is important because, as The Phantom of Mongolia plainly states, the Road Warriors got over in Japan by working American TV matches in Japan. On March 8 in Funabashi, Khan and Animal Hamaguchi were steamrolled by the debuting team in less than four minutes. Six days later in Nagoya, Khan and Choshu challenged for the Warriors’ AWA World Tag Team titles, in a match that ended by double-countout in 5:35. Ozawa noted that most would never have gotten away with this, but it got over for the Warriors. As he put it, they had both the drawing power and the "persuasive power" to make it work. After the Tenryu match, Khan flew to Tulsa for his only American match of the year, where he and Hercules Hernandez came up short against the Rock ‘n’ Roll Express. Then, he went to Australia. This was at the same time that Stan Hansen and Bruiser Brody, the latter of whom was transferring to New Japan, had been booked there by Larry O’Day. Outside of recalled interactions with Hansen and Brody (the latter of whom, he claimed, asked to learn his version of the diving knee drop), and a match against Ron Miller on a show he promoted, Ozawa did not recall much specific detail about the tour. I could not find cards for these shows online, although I suspect some info could be found in contemporaneous Weekly Gong issues; according to Hansen’s 2010 autobiography, The Last Outlaw, Gong-affiliated photographer Jimmy Suzuki was there to shoot them. The Last Outlaw also contains an incredible anecdote about a trip to the zoo. Simply by leaning one hand on the glass, Ozawa provoked the zoo’s gorilla, who uprooted a tree and flung clumps of dirt towards him to assert his threatened dominance. This earned Killer Khan a new nickname from Stan: King Kong. When Ozawa returned home, Japan Pro held its first tour; the one-week Big Lariat Festival, with All Japan’s talent, ring and resources, and with Hansen. Khan brawled with Stan on May 17th, a match which has since circulated via a camcorder recording. In early June, Ozawa came down with acute lymphangitis. Khan and Yatsu were set to wrestle the Road Warriors on the 4th in Osaka, and Khan barely managed. As he claimed, he was hooked to an IV drip backstage, and the unaired match was carried by his partner. Ozawa was back to work by the time the next tour began, but he missed AJPW’s Special Wars in Budokan on the 21st: All Japan’s first show in the building since 1977, and the first in puroresu as a whole since 1980, which was booked with Naoki Otsuka’s help. It would have been Ozawa’s first match in the building since February 1977. Jumbo Tsuruta is wheeled out with a worked knee injury after Khan's diving knee drop. Japan Pro’s second tour in August had been sold around Choshu’s first singles match against Jumbo, which was booked for August 5. But Jumbo needed to be written out for a hospital visit. On August 2, Khan & Choshu wrestled Tsuruta & Tenryu, and the Killer’s knee drop was rolled back out to inflict a worked knee injury. As Jumbo entered the hospital—where he was to learn that he was carrying hepatitis B—his match with Choshu was given to Yatsu instead. After that match, on August 5, Choshu took to the mic for a famous promo, declaring that it was no longer the era of Baba and Inoki. For all of Riki’s popularity, Ozawa did not see it that way. That old, long-estranged duo still carried their respective companies in provincial markets. Nor did Ozawa necessarily consider himself part of this ‘new era’: being a JWA alumnus, no matter how late in that company’s life, still loomed large in his mind. On September 14, Khan and Yatsu teamed up for a title shot against Jumbo & Tenryu. After that tour, Khan returned to Australia for a show, though he did not remember the opponent. (To him, that trip was most memorable for a chance encounter with Jiro Yanagawa.) In October, AJPW returned to prime-time after six-and-a-half years at 5:30. This was not directly due to the momentum of the Japan Pro feud; rather, it was a reward for the success of two Saturday Top Special broadcasts in March and June. Khan’s last matches of the year were on JPW’s third and final tour, the New Wave in Japan shows of early November. He had a rematch against Terry Gordy at Osaka-jo Hall. As for Japan Pro, their dream to be a truly independent promotion was foiled as the year ended. Talks for their own TV deal with TBS only materialized in a single special broadcast that December. and the company folded under pressure to sign to NTV. 1986 would only see three shows booked under Japan Pro’s banner. That January, Ozawa traveled to Saudi Arabia and Oman alongside Ryuma Go and the diabetic Mr. Chin, who got the group detained at Saudi customs over his insulin. These shows were booked by Tiger Jeet Singh, who Ozawa wrestled in Arabia. He recalled that the two had a “reasonably exciting” match; “I don’t think Singh was that good at wrestling, but he knew what wrestling was all about.” (Ozawa claimed that he declined Singh’s offer to work a show in South Africa in late 1987: the show which Haru Sonoda took on instead as his tragic honeymoon trip. It seems to me, though, that Ozawa would have still been working with the WWF when Singh made the offer.) According to an old rumor, Ozawa beat Go so badly in a game of oicho-kabu that he drove him into debt. The Phantom of Mongolia partially confirmed this. The game was real, and the stubborn Go lost all his gambling money, but Ozawa did not ask for more than that. Back home, though, Khan spoke about the game in the Japan Pro waiting room. Someone pulled a rib on Go and stormed the Kokusai Ketsumeigun waiting room to demand he pay up. Ozawa insisted he was not in on the joke, but his sympathies were limited: Go had brought it on himself. Khan’s first Japanese tour of the year, the three-week Excititing Wars [sic], culminated at the Budokan. All Japan and Japan Pro faced off in five singles matches, and Khan held up his end in the second bout, beating Mighty Inoue in under five minutes. On the following Champion Carnival tour, Khan took part in a five-man tournament for the United National title, which Tenryu had vacated after losing a pinfall, and his and Tsuruta’s tag titles, to Yatsu in February. (Since Japan Pro had signed with the network, the respective number-twos of their factions had gotten clean pinfalls on each other.) All of Khan’s matches ended in his loss or draw by disqualification. In April 1986, Ryuma Go was one of the three wrestlers (and referee) who were cut to make room for the Calgary Hurricanes: Super Strong Machine, Shunji Takano, and Hiro Saito. With Kokusai Ketsumeigun mutilated down to just Rusher and Goro Tsurumi, the Great Kabuki and Ashura Hara joined them. Then, in June, Khan was part of a further bit of reshuffling when he left Japan Pro to wrestle with the Hurricanes as a ‘freelancer’. At the company’s request, he began to paint his face and wear a black hood—evoking the Ku Klux Klan—and had a short summer feud with Choshu. In several buildup tags throughout July, most notably a shot at Choshu & Yatsu’s tag titles on the 21st, Khan turned up the heat. He took scissors to Riki’s long black locks, which led commentator Kenji Wakabayashi to call him “the ungrateful Killer Khan”: as if Ozawa had been Choshu’s junior. He even brought a noose to the ring, and used it, more than once. On the last night of the month, the two had a bloody death match in Tokyo, where Choshu survived the diving knee drop to overcome Khan. The match has long been held in high regard, at least by overseas fans of the period, but Ozawa’s subsequent commentary displayed no such fondness. In a 2018 interview, he stated that the plan had been for Riki to kick out of the knee drop, and then roll out of the ring to recover. That is not what Riki did. Rather, Choshu continued to lie in the ring, as Khan, holding up three fingers, staggered to the outside in shock over the kickout. If Ozawa's claim is correct, it is apparent that Choshu’s audible went against the intended transition, and goaded Khan to come back into the ring and hit a jumping knee drop to the back of Riki’s head. To Ozawa, this was where Choshu crossed a line. Right after Choshu kicked out for a second time, as Khan still laid on top of him, he pointed to the crowd. While he didn’t notice at the moment, Ozawa was offended when he saw what Riki had done to denigrate the false finish. Choshu won that match after two successive Rikilariats, but he claimed that had he known, Khan would have taken three or four to go down, and then he would have stood and walked to the back: “I think Baba would have forgiven me.” In the back half of the year, Khan was clearly spinning his wheels. He wrestled a few matches with Rusher, while Hara shacked up with the Hurricanes. The All Japan vs. Japan Pro rivalry had run its course, while even Choshu was overshadowed by the signing of retired yokozuna Hiroshi Wajima. Khan teamed up with Terry Gordy for his second and last Real World Tag League. He had a good time doing so, but the team had just been thrown together. Only their first match, against Jumbo & Tenryu, made it to television. This was Khan’s final televised match in Japan. The team ended the tournament with eight points. Khan sat out the first third of 1987’s first tour, and after its end, the family moved back to Florida. He prepared for his return to the WWF, now a much different company under the junior Vince McMahon. He had obligations to work one more show in Japan, the April 2nd date at the Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium. By this point, Japan Pro Wrestling was little more than a front for Otsuka as a show promoter (he was also working for the upstart joshi promotion JWP), and he was the one who promoted this show. For his last match in his native country, Khan teamed up with Ashura Hara to beat Kabuki and Motoshi Okuma. He was out of the loop on the turbulent state of “Japan Pro”, but caught wind that Choshu had been expelled from the company, and was confused. He did not have a chance to speak with Riki, and three weeks after Osaka, he was taping squash matches for WWF Superstars. This new take on the Khan character, which was “set up by the WWF office”, deemphasized the Mongolian origins. He was a client of Mr. Fuji. He wore geta to the ring. Ozawa even leaned into his sumo experience for pre-match rituals. It was only in this final run that Khan used poison mist, which he claimed in his book not to care for. But it was his idea to start growing his hair again (it had been shaved during the André feud), to distinguish himself from the Iron Sheik. He played along with the junior McMahon’s new sports-entertainment product, but Ozawa later noted the disdain he felt when wrestling with similar sensibilities entered Japan. I will quote an excerpt from The Phantom of Mongolia. "To someone who does not know much about wrestling, a celebrity in the ring and a Japanese man dressed as a Mongolian, Killer Khan, may seem to be the same thing. However, I have my own pride in the fact that I learned wrestling from the ground up, trained and devised, built up my achievements one by one, and eventually came out on top. When I see Takada on TV putting people in the ring who have not had any serious training, and eventually leaving the world of wrestling to imitate TV personalities, I feel a sense of despair. If Kotetsu-san were alive today, he would have beaten Takada to a pulp. I understand that everything must change with the times. However, if you put an amateur in the ring and let him beat a wrestler, that is the end of wrestling." By July, Khan had started a program with Hulk Hogan which ran across the United States over the next few months. There were even a couple Mongolian Stretcher matches in there. In The Phantom of Mongolia, Hogan certainly doesn't receive the effusive praise given to Jack Brisco or André the Giant, but the Hulkster’s charisma and drawing power went a long way for Ozawa. While Hogan occasionally “puzzled” him in the ring, and he “certainly wasn't a good wrestler, he was not a bad wrestler, either.” (Masashi claimed that he had encouraged Hogan to enter the business in Florida back in 1979. This is absolute nonsense.) It was also in July when Ozawa learned the truth, courtesy of a magazine sent by a fan: Choshu was going back to New Japan. To Ozawa, it was “hard to believe” that Choshu would return to New Japan after he had gotten so fed up with it. Tiger Hattori spilled the tea. He told Masashi about a meeting that Choshu had made at New Japan’s headquarters, and about another discreet talk with Inoki during a provincial tour. He told him about the money that enticed Choshu, over the objections of Yatsu and others, to boycott All Japan when Baba tried to sign everyone to a new contract. Ozawa contacted others to try to get the story straight, and they corroborated all of it. Ozawa’s rage and disgust over Choshu’s actions soured him on the entire business. He spent a few months punching the clock, but had resolved to retire. Cindy strongly objected, and his coworkers tried to dissuade him. When Masashi told McMahon that he was quitting, Vince urged him to reconsider and promised that he could resolve whatever trouble he had gotten back home.[2] Even Hogan came backstage one night—slipping out of the babyface locker room, driving to the other end of the arena, and entering the heels’ room—to try to sway Ozawa. In retrospect, he himself admitted that he should have stuck it out for a few more years for his childrens’ sake. But he would not be deferred. Killer Khan’s last match with Hogan took place in Nevada on November 15. WrestlingData claims that his final match was on December 1, 1987, wrestling Jake Roberts to an unknown result. However, Ozawa claimed that his final match was against George Steele in New Jersey “at the end of the year”. If this memory is correct, it would have been on December 13, 1987. FOOTNOTES

-

Killer Khan

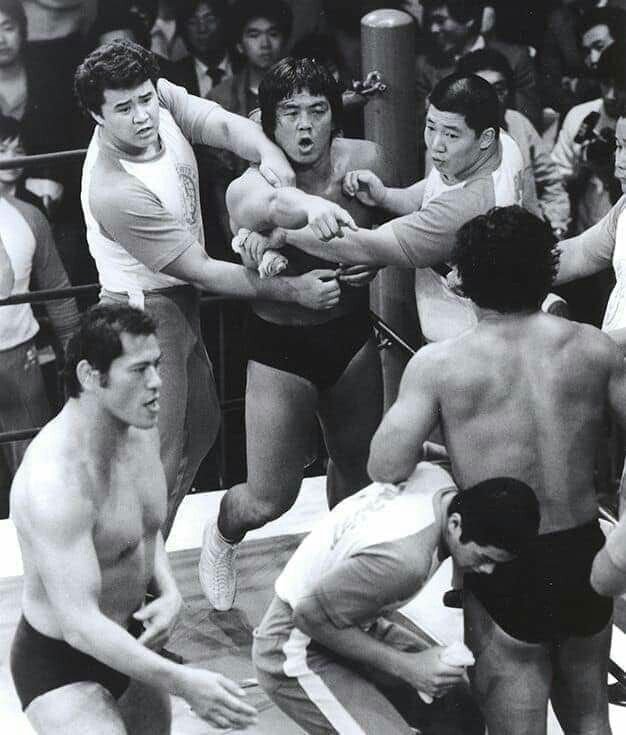

PART THREE: FROM TOKYO TO TEXAS (1983-1984) In October 1982, Riki Choshu's heel turn changed the course of Khan's career. If Killer Khan preferred working overseas, why did he spend almost all of 1983 back with New Japan? To answer that, and to set the stage for much of the rest of his career, we need to take a step back. After the International Wrestling Enterprise had finally died in the summer of 1981, its former ace Rusher Kimura invaded New Japan in the fall. Rusher’s Kokusai Gundan trio with Animal Hamaguchi and Isamu Teranishi became the most despised heels in the country, and his matches against Inoki drew multiple television ratings over 20%. By the following autumn, the company had plans to replicate the formula and give its other two top draws—Tatsumi Fujinami, who had broadened Nooj’s audience to women and young adults in the late seventies, and Tiger Mask, for whom children had flocked to the product in the early eighties—their own Japanese heels. On the Toukon Series tour, Riki Choshu and Kuniaki Kobayashi came back from Mexico, and effectively turned heel. On Choshu’s very first match back, a six-man tag with Inoki and Fujinami, he caused the whole thing to fall apart in his refusal to accept his implicit position below Fujinami. In kayfabe, New Japan held a board meeting where Shinma demanded that Choshu be punished for insubordination, only for Inoki to instead give him a singles match with Fujinami: two, in fact, with the latter being a shot at his WWF International Heavyweight title. As the tour ended, Choshu prepared to leave with Masa Saito for the end of the year. That is where Killer Khan enters the story. As Ozawa later wrote, Choshu and Saito invited him to dinner at the Keio Plaza Hotel. (The Phantom of Mongolia claims that this meeting occurred after their return to Japan, but due to a press statement I will refer to later, I am certain that Ozawa misremembered.) Saito had long been disgruntled with puroresu’s pay gap, and he was far from alone. These men acknowledged and accepted that their business depended on top foreign draws, and that those superstars came at a premium. Where Saito and company had an issue was the second-tier gaikokujin, the “obviously mediocre” talent who were still paid far better than native workers: the men who, as Masa pointed out, were of lower standing in the States than he and Khan were, yet were paid three times as much. If Saito and Khan signed on with New Japan to take the place of the second-tier foreign talent, they would be cheaper. Of course, if the experiment was successful, they could leverage that for better pay. And frankly, Choshu needed them. The company had big plans for Riki, but Riki had a major flaw: he was pretty lousy at working with foreigners. This was somewhat mitigated by the nature of his role, which at this point didn’t really call for big singles matches against gaikokujin, but that still left tag matches. To pair Choshu with a foreign heel, à la Umanosuke Ueda (and Tiger Jeet Singh), would not have worked well either, and Kobayashi was only a junior heavyweight, so he needed other Japanese wrestlers who could compensate for his limitations and function as heels in their own right. Saito and company pitched the idea to Hisashi Shinma, and while he was unsure whether it could work, he was on board. The company certainly needed to cut costs, but Shinma promised that, if the angle drew, he would raise their salaries. For whatever that promise was worth. On November 18, Khan made a public statement that he, Choshu, and Kobayashi would “play a central role in reforming New Japan, or rather, the Japanese wrestling world”. On the first televised show of 1983, Khan turned on Sakaguchi during a tag match against Choshu & Saito. Thus, Kakumeigun (the “Revolutionary Army”) was born. Kakumeigun celebrates Choshu’s title win. On the second tour in March, Khan was part of an eight-man “Asia Zone” preliminary league for the inaugural IWGP Series tournament, which would replace the MSG Series that May. This gave him his first singles matches against the company’s top heavyweights, and he went down for Inoki in the last show of the tour on March 24. One last qualifying match saw Khan go against his teammate Choshu at the start of the next tour, on the first of April. Choshu got himself disqualified for shoving referee Mr. Takahashi, so Khan got on the IWGP bracket. Two days later, Choshu got the consolation of beating Fujinami for his title. As Ozawa wrote, Riki’s popularity could not be denied, and their relationship was a long way from where it would end up. Even at this early juncture, though, he recalled that he was privately put off by Choshu’s misogyny. Kakumeigun expanded its ranks. Neither Ozawa nor Saito planned to stay in Japan forever, and with their blessing (“he approached us personally”), a fourth heavyweight and a second junior joined: Animal Hamaguchi and Isamu Teranishi, whose Kokusai Gundan split up during a match in April. With a second heavyweight who lived in Japan, Saito was now free to return to the AWA, which he did at the tour’s end. Khan would get a tour’s worth of time off, but not until after the IWGP Series. Khan reached the semifinals: a rematch with André, which went to a double countout. When the tour ended the following night, Andre won another singles match. Just as Ozawa left, the levee broke. NJPW sales manager Naoki Otsuka read over the company’s shareholders report, where he discovered that his company that had made two billion yen in sales only recorded a profit margin of ¥26 million. As was quickly apparent, Inoki had covered his losses from the failed biotech startup Anton Hi-Cel through flagrant financial abuse. --- Anton Hi-Cel is not essential to Khan's story but is too fascinating to leave out. Ozawa believed that the germ of what became Anton Hi-Cel had been a sound and noble idea. In late 1975, during a party at the Imperial Hotel, Inoki had told him of his plans to build an “Inoki Palace”: a successor to Rikidozan’s ill-fated Riki Sports Palace in Roppongi. This venue would have made jobs for his former wrestlers (not unlike Mitsuharu Misawa’s late-life dreams to open a steakhouse and develop vocational rehab programs with Pro Wrestling NOAH’s sponsors). But somewhere along the way, Ozawa felt Inoki must have “lost his screws”. In 1977, Inoki’s little brother Keisuke transferred from the sales department, where his limited command of Japanese had hampered years of Hiroshima sales, to the head of the Anton Trading business. A string of failed side hustles followed. Anton Rib was a restaurant centered around Inoki’s own spare-rib recipe. Anton Goods sold yerba mate tea and sunflower seeds. Thanks to his English tutor, a friend of Walter S. McIlhenny, Inoki even got a distribution deal with Tabasco in the early 80s; that product only took off in Japan after he lost the rights. But the most ambitious and the most calamitous of these pursuits was Hi-Cel. After the 1973 oil crisis, Brazil started to mitigate its dependence on foreign oil by blending all gasoline with locally sourced ethanol. When the sucrose has been squeezed out of sugarcane, there is still a substantial amount of ethanol in the remaining pulp, known as bagasse. Unfortunately, once you oxidize that alcohol out of bagasse, the pomace that remains becomes aldehydic waste. Under what he later ascribed to the “deception” of Brazilian government officials, and likely at Keisuke’s encouragement—the younger Inoki took responsibility for the debacle shortly after Kanji’s death, in a talk with Masahiro Chono—Inoki formed Anton Hi-Cel in 1980. The company commissioned research by Hayashibara, a legitimate name in biotech which later became the world’s first company to mass-produce the trehalose sugar. Their goal was to develop a new cattle feed whose enzymes would break down bagasse’s lignin and make it digestible for cows. Even in his autobiography, written fifteen years after the company's fall, Inoki insisted that Anton Hi-Cel had been meant for the good of his wrestlers. But that was not how they saw it. NJPW’s salesmen were made to buy Hi-Cel bonds (which they sarcastically dubbed their “registration fees”) and shill vacation homes. Fujinami had been forced to borrow tens of millions of yen from his in-laws. When Ozawa came into the office to receive his bonus for the MSG Series final, he was given an envelope of cash, then ordered to sign a blank receipt: a clear sign that money was being funneled. By 1983, the company had failed. There were several causes: a massive inflation wave; Hi-Cel’s failures to ferment the pulp, due to the difference between Japanese and Brazilian climates; and finally, their ranch’s requisition by the Brazilian military. At the end of it all, Inoki was several billion yen in debt, and a ¥1.2 billion pledge from TV Asahi, with New Japan’s broadcast rights as collateral, was not enough to plug up his wallet. --- Ozawa knew that he could make it in the States, so his livelihood was not dependent on the matter; nevertheless, he supported what happened next. As Ozawa took his tour off, the “coup” took place. We should not get mired in the minutia of the matter, as these particulars are not particularly relevant to Ozawa, but it deserves some summary. Top wrestlers and executives met in July not to plan a coup, but a company. Many wanted to form a new promotion named after the TV program, World Pro Wrestling Ring. A second faction around Tiger Mask, and his sketchy new manager Shunji Koncha, wanted to form a private production company centered around him. After the end of the tour, Sayama suddenly retired (and unmasked, unprompted, on TV Asahi variety show How Far Will Kin-Chan Go?). The plan was downscaled to a coup when central conspirator Kotetsu Yamamoto failed to secure the necessary capital for WPWR. Just before Khan’s return tour began, at a shareholder meeting on August 25, Inoki and Sakaguchi stepped down, and Shinma was dismissed outright. They were replaced by the troika of Yamamoto and network executives Kazuharu Mochizuki and Hiromi Otsuka (no relation to Naoki). As Ozawa points out, though, the original plan to form a new company had reflected the conspirators’ belief that they could not “win the fight” to oust Inoki from New Japan. That belief bore its bitter fruit. Top TV Asahi executives Koshiji Miura and Hiroshi Tsujii, who had promised to protect Inoki and Sakaguchi “for the rest of their lives” when they joined forces in 1973, threatened to pull the plug on World Pro Wrestling if the pair were not reinstated as executives. At a shareholder meeting on November 11, that was exactly what happened. Ishingun in the Philippines in February 1984. The autumn was not without interest in the ring. Kakumeigun changed its name to Ishingun: revolution became restoration. The company saddled them with a new member to rub off on, the returning Yoshiaki Yatsu. At the end of the Toukon Series on November 3, Ishingun got four singles matches against New Japan’s “main army”, and Khan got the only title bout among them, against Fujinami. Though their match, the third, ended in a double countout, that still gave Ishingun the lead; Inoki’s victory against Yatsu hardly proved anything. However well his faction was booked, Ozawa was demoralized by the coup’s failure, or at least the lack of meaningful change. Sayama and Shinma were gone, sure (not that Ozawa had anything against Sayama), but his wages had not improved. In the last full tour that he ever worked for New Japan, Khan teamed up for his third tag tourney with Toguchi, who had already planned to base himself in the WWF. They did nowhere close to the previous year’s dark-horse showing and did even worse than their debut. The following February, Khan worked his last dates under the lion’s mane: the pair of shows that New Japan promoted in the Philippines. The last match of these was another shot at Fujinami's title, which ended in double-countout. Khan with Shogun KY Wakamatsu during his only Stampede run. Khan's return to North America began with his first work in Canada, which was spurred by Stu Hart’s request through the WWF, and his reunion with Mr. Hito. Hiro Saito, Junji Hirata, and Shunji Takano were also working in Calgary; unlike that trio, who lived in the restaurant basement of Hito’s friend, Ozawa bunked with Adachi and his wife. The couple were upset that New Japan never paid them for the coaching that Hito gave their talent, but they declined when Ozawa offered some money. Khan wrestled under the services of manager and former IWE wrestler Shogun KY Wakamatsu. On January 20, at a Calgary show promoted by Gene Kiniski, Khan won the North American Heavyweight title from Archie Gouldie. This was a full-circle moment for Ozawa, for whom the Mongolian Stomper had made a powerful impression, even before Masashi’s first match, with a Korakuen house show squash against Great Kojika. Khan held the belt for exactly seven weeks, as a program with the Dynamite Kid—which, as Ozawa wrote, would never have happened in Japan—led to a title change in Calgary. The feud lasted one more week, ending when Khan lost a loser-leaves-town match at the Victoria Pavilion. After leaving town, and taking April off, Khan began his last Southern run. Through the end of the year, he worked about a dozen Mid-South dates, which included a pair of title shots against Magnum TA, and one-offs in Florida and Kansas. But he set up shop in Dallas, with World Class Championship Wrestling. When the debuting Khan was given the WCCW television title due to Kelly Kiniski’s injury, he worked a program with Kevin von Erich, who won it from him on May 21. For the first time in five years, Ozawa saw an old JWA senior. Now, that man was the Great Kabuki. While certainly different from Khan in the ring, the two had a certain kinship. Ozawa wrote that his big break made him as happy as it would have been if it were his own. Neither would have reached the top in Japan, but in America, they had become, alongside Masa Saito, the great Japanese heels of the eighties. But supposedly Singaporean kabuki warriors do not work with supposed Mongols. Instead, Kabuki teamed up with Magic Dragon (the last of AJPW’s first three trainees, Kazuharu Sonoda), while Khan reunited with manager Skandor Akbar, for whose Destruction Incorporated stable he wrestled alongside the Missing Link. As readers will know, World Class’s top babyfaces were the von Erich brothers, the eldest of whom, David, had recently died in Japan. Ozawa put it bluntly; the von Erichs that he got to work with were nice kids, but they were still “a little thin” for their spot, and “their personal lives were bullshit”. On those nights when the speed hit a little too strong, their jerky movements might have thrilled the crowd, but they threw off the men they were working with. Ozawa also met the Fabulous Freebirds. Buddy Roberts, who had made several trips to New Japan in the seventies as one half of the original Hollywood Blondes, claimed that he always knew Ozawa would make it if he made it to the States. Roberts, Terry Gordy, and Michael Hayes were all good at their job, but it was Gordy who stood out to Ozawa, and it was Gordy to whom he drew closest. In kayfabe, Khan passed down his Oriental Spike, a chokehold which pressed one’s thumb into their opponent’s trachea, to Gordy. On one flight from San Antonio to Dallas, the pair downed three bottles of Jack Daniel’s in half an hour. Ozawa lost track of Terry when they arrived at DFW, but then he found him, dancing on the luggage conveyor belt. As the Freebirds wound down their feud with Fritz’s boys, and prepared for an ill-fated WWF run, Gordy feuded with Khan. At the Labor Day Star Wars show, Khan beat Gordy in a ‘spike’ match, weakening the Freebirds before the Cosmic Cowboys beat them on their way out of Dallas. Back home, things were going crazy. During his time deposed from the New Japan board, Inoki had tasked Shinma with forming a new promotion: the Universal Pro-Wrestling Federation. Inoki sought a second source of funds and courted Fuji TV for a television deal. Even when Inoki was reinstated, the plan remained for the UWF to function as a second brand; he had told Akira Maeda that he would eventually follow him to the new company. All this never materialized, as TV Asahi swiftly added network exclusivity clauses to all their contracts, but the promotion was too far along to scrap. (Ozawa's memories were fuzzy, but he wrote that he might have also signed an agreement with the network.) The UWF held its first shows in April, where Khan’s likeness was put onto one of wrestling’s all-time great bits of false advertising. The poster for the UWF’s first shows, on which Shinma loomed largest, teased twenty top wrestlers from New Japan and overseas, including Khan, as possible appearances. In the summer, the UWF sacrificed Shinma and a potential WWF partnership to bring Sayama back into pro wrestling. With the rechristened ‘Super Tiger’ as its midwife, the UWF gave birth to a deconstructed form of pro wrestling, which would become known as shoot-style. At the end of the previous year, Naoki Otsuka had resigned from the sales department to form New Japan Pro-Wrestling Entertainment. Cracks formed through the first two-thirds of 1984, until things shattered outright in August. New Japan canceled a show that Otsuka had put together at Tokyo’s Denen Coliseum to work a short Pakistani tour; then, through the mediation of Gong magazine guru Kosuke Takeuchi, that show was revived as an AJPW event. As he returned from Pakistan, Inoki terminated New Japan’s association with NJPW Entertainment after the already-booked September shows. Two days after that Denen show, which saw Mitsuharu Misawa’s debut as the second Tiger Mask, Otsuka publicly announced that he would pull wrestlers from his former employer. It just so happened that NJPWE was in charge of Riki Production, Choshu’s personal entertainment company. Shortly after Otsuka received his notice, he met with the members of Ishingun at Choshu’s apartment. To Ozawa, who only kept track of all this through Japanese magazines sent to him by fans, these developments were New Japan reaping what it had sown. He respected and quietly rooted for the post-Shinma UWF, hoping that his “cute juniors” Sayama and Maeda could make their “martial-arts route” get over in Japan. While Ishingun’s allegiance to Otsuka would not become public until September, he also supported any new place for his countrymen to work; he certainly had no desire to ever work for Nooj again. As for himself, though, Ozawa did not want to get entangled any deeper in Japan. He had vague plans to come back home eventually, but only after his retirement, as a restaurateur. The NWA was beginning to buckle against the WWF’s national expansion, but Killer Khan was making good money in Dallas, and he figured that this would still be more stable than returning home. Then, Ozawa got a call from Otsuka. Naoki told him that the rest of Ishingun, and several more, had thrown in their lot with him, and they needed Khan. He also told him that, while the end goal was to establish (what would be known as) Japan Pro Wrestling as its own promotion, the company would lay the groundwork through a program with All Japan. And it would be “glass-walled”: that is, the finances would be transparent. Politely, Ozawa declined, but a few days later, he got another call: this time, from his old roommate. Haruka Eigen had gotten in on the ground floor as one of NJPWE’s investors, and he insisted that the company would be glass-walled. He also leaned on his yakuza connections when he told Ozawa that he would get “a free ride” from a certain boss if he returned to Japan. Ozawa took this as an implicit threat, but the insistence broke him down. If they needed him that badly, he would cooperate, but only if he could still work in America. On September 27, three days after Ishingun had declared their allegiance, Khan and Otsuka held a press conference at the Capitol Hotel Tokyu. (Many years later, Ozawa learned that Japan Pro had originally set aside twenty million yen to sign him; he had only gotten three million.) Ozawa returned to Dallas. Then, too, did Gordy. After ditching the Freebirds’ ill-fated WWF run, he assaulted Khan during a match in Fort Worth, and the feud hit fever pitch. After a match for Polynesian Pro on November 14, the two were set to square off in a Texas Death Match for Thanksgiving. The André feud might be Khan’s most famous American work as a whole, but if a single Stateside match must be cited in his legacy, it cannot be one that he worked with the Giant. With Kerry von Erich serving as guest referee, Khan and Gordy had one of the great American bloodbaths of the era. In 2011, members of the DVDVR message board rated it the best Texas match of the decade. When asked about his favorite match by Tokyo Sports in 2021, Ozawa himself cited the Texas Death match first. Khan’s last match for Dallas was a cage match against Gordy on December 7. Then, with Cindy, Yoshiko, second daughter Yukie, and nine-month-old David in tow, he left for Japan. The plan was to stay for a year, and Ozawa decided to rent a house which Choshu had bought in Setagaya, near the Japan Pro office and dojo. He would come to deeply regret this choice, as it isolated Cindy from the English-speaking community that she would have found in a district like Roppongi. Though he did not wrestle, Khan appeared at Japan Pro’s second show on December 13. At some point, when the wrestlers met for drinks at an izakaya, Choshu rallied his coworkers: “This is the last group for us. If it fails, we will all quit wrestling together.”