Everything posted by KinchStalker

-

Entrance Music

Oh right, I forgot about Rolling Dreamer! That was produced in 1979, but they didn't start using the instrumental version as his theme until 1980.

-

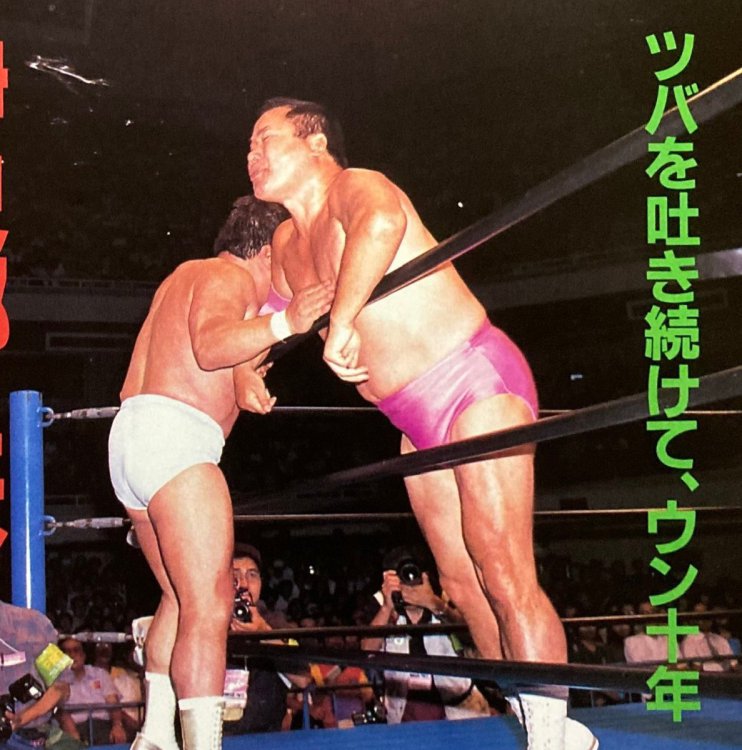

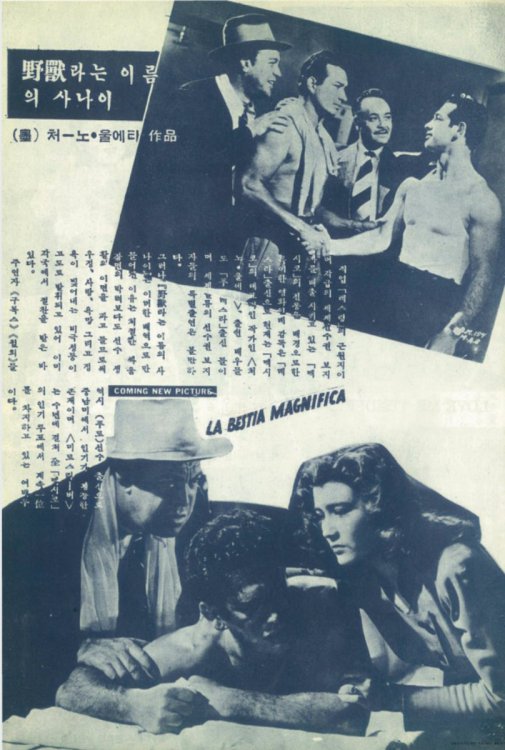

[1953] The Magnificent Beast

La Bestia Magnifica ("The Magnificent Beast") 1953 Películas Nacionales Directed by Chano Urueta, a pioneer of both Mexican horror and lucha cinema, La Bestia magnifica started the wrestling feature film in Mexico. Starring actor-luchadores Crox Alvarado and Wolf Ruvinskis (the future Neutrón) alongside actress Miroslava Stern, the movie contained three full matches. These involved lucha legends such as Enrique Llanes and Rito Romero. A print of the film found its way to South Korea as early as 1957. Half a decade later, its wrestling scenes were studied by Korean wrestling pioneers Jang Yeong-chol and Chun Kyu-deok. A 1957 issue of Korean magazine Screen advertises the film.

-

Rock and wrestling

Here's Bob talking about wrestling on Minneapolis public access TV in 1999.

-

Entrance Music

What makes a lot of early puroresu entrance music so novel is that it was often material that 70s television networks were licensing to use anyway, not just for wrestling. Specific commissions were rare; off the top of my head, Inoki, Sakaguchi, Fujinami, the Funks, and Ashura Hara were the only ones in the 70s. (And I'm not 100% sure about the Funks! That could be a Sunrise situation, where the song already existed.) "Sky High" had a string arrangement by Richard Hewson. Billy Robinson's "Blue Eyed Soul" was a Hewson arrangement. Dick Murdoch's AJPW theme, "Love Bite", was directly credited to The Richard Hewson Orchestra. Later on, you have smooth jazz fusion saxophonist Tom Scott providing music for the British Bulldogs as well as Akio Sato & Takashi Ishikawa's tag team. Meanwhile, you had NJPW's love of disco-era Maynard Ferguson. Hogan came out to his "Battlestar Galactica", Masked Superstar had "The Fly" from Conquistador, and Ryuma Go used his cover of EW&F's "Fantasy" on at least one occasion. (Not wrestling, but Nippon TV used Ferguson's Star Trek theme cover for one of their most famous game shows, Trans America Ultra Quiz. See what I mean about production music?) Unrelated, but I want to buy a drink for whoever on TV Asahi's production staff decided to license the Waterboys for Billy Jack Haynes in 1985.

-

Entrance Music

It's "Zero To Sixty In Five" by Pablo Cruise. At least that's what they actually came out to, couldn't tell you what they dubbed over on the DVD releases.

-

Gilmour vs. Waters

Pompeii Deathmatch over whether Roger gets to post on Pink Floyd's social media accounts, which everyone knows he will use to promote the 40th anniversary remix of The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking. You've got thematic props for the big albums, but I would book the Amphitheatre for sheer atmosphere. Ring in the center, with a replica of the band’s Pompeii stage set in front. 15-foot Wall in one corner, for someone to dive off of at one point. The brawl spills into catering, and Dave bumps onto Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast. He does not, however, bump onto Rick’s organ despite repeated teases, out of respect. It turns out to Dave's horror that, with quiet reflection and great dedication, Roger has mastered the art of karate! But Polly interferes and hits a low blow, which Roger oversells with the first Careful With That Axe, Eugene scream since Oakland ‘77.

- Masami Soranaka

-

Puroresu History on Indefinite Hold [NEW UPDATE]

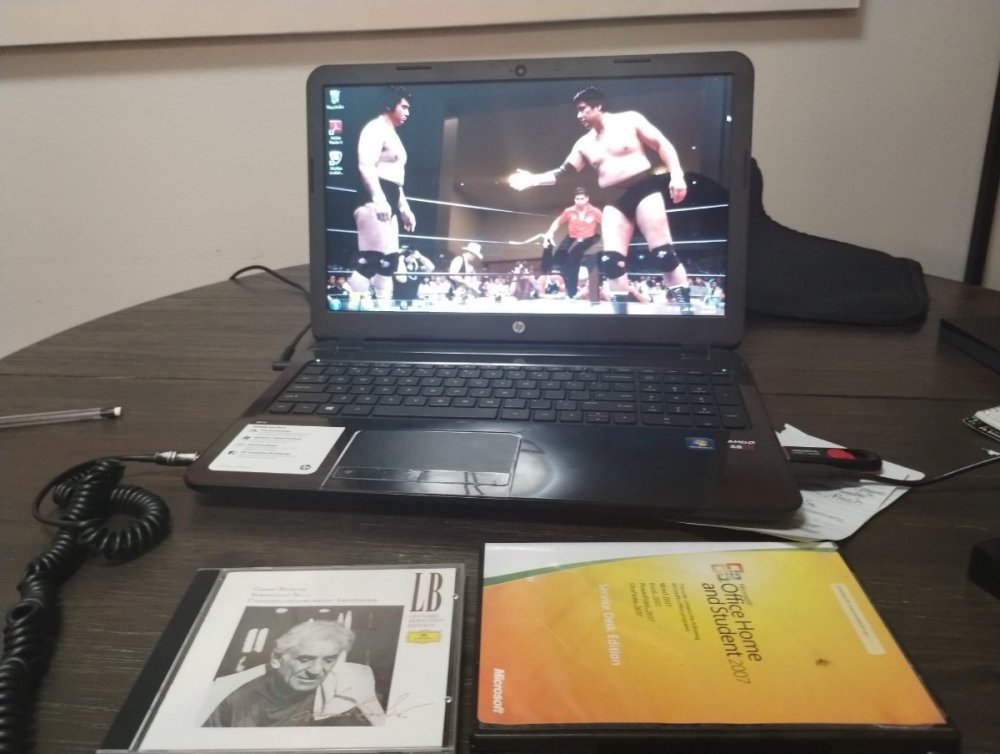

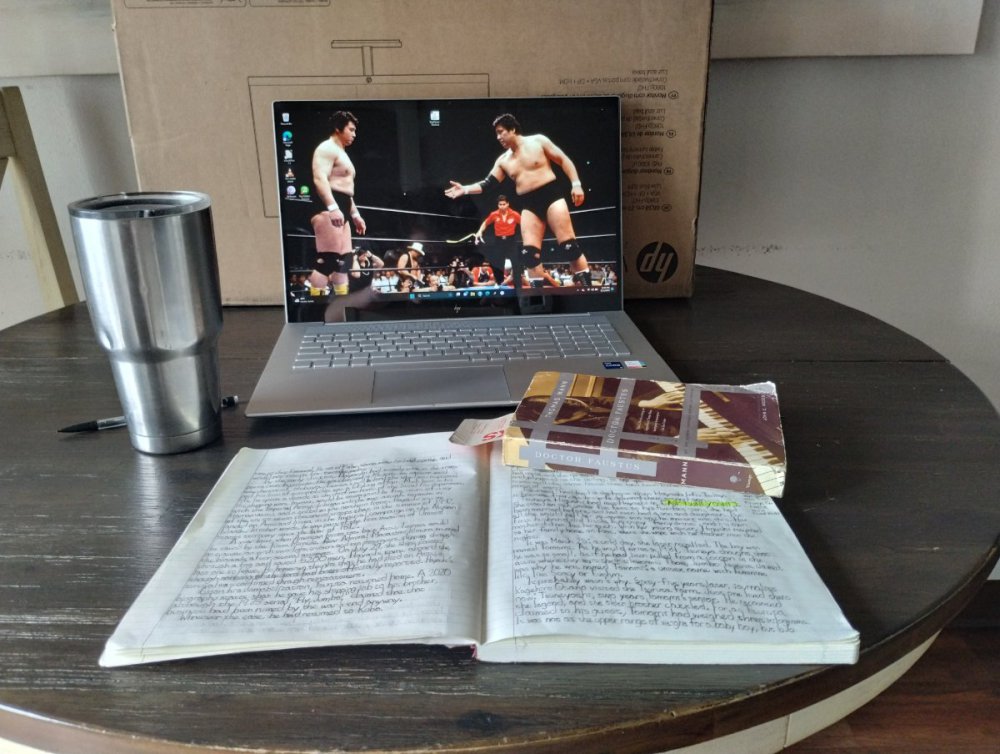

This is the final update. I received my new laptop on Monday. It's in the midrange of what I wanted, but it will serve my needs much better than the 2009 HP. However, I am taking a small vacation from serious puroresu research. This is where I feel I need to pull back the curtain for you guys. For the past two years, my transcription and research have not just been a hobby, but my life. I can afford to invest so much time into it—in other words, I can afford to transcribe entire books with an app that only transcribes four characters at a time—because I am unemployed and live in a residential care situation. It has been rewarding to accidentally become an expert on Showa period puroresu, don't get me wrong; there is still a great thrill to uncover so much information that was simply never going to get through to the West, filtered as that range of knowledge has been through Meltzer (and Fumi Saito). It is not a life I can live forever, though. The tedium of transcription, which you could definitely feel seeping into my Four Pillars book recaps, has been very taxing on my mental health (the best analogy I can make is to imagine if you were forced to sit down and solve hundreds of captchas every day). There are simply no English-language resources that are of any use to me when it comes to detailed historical coverage of puroresu. This has been such a major part of my life that I have literally not read a book in years. When I went to AEW's Portland show in January, I knew nobody, and felt the loneliest I had in a long time. I have made friends through wrestling, to be sure, but they're all screen friends. I want to build a healthier, more sustainable relationship with this hobby in 2023. I am planning to find some part-time work this year that will not impact my benefits. This will cut into the time I have to transcribe Japanese materials, but I hope that I can use extra funds to commission proper translations of Japanese articles. I want to spend time to make some in-person social connections. I certainly want to continue my weight loss! (I was 310 last February and have gone down to 265. I want to at least be under 230 by the end of the year.) So, please do not expect much from me here for a little while. Right now, the only puroresu work I am doing is a longhand draft of the first chapter of a Jumbo biography, which I am writing out to assess what details I may need to seek an interview with Tsuruta's brother to gather. (Hopefully I can give the guy some money to answer my questions.) Meanwhile, I am reading my first book in years. It's one that I only got halfway through in 2016; getting dumped by my high school sweetheart left me in no condition to finish it. But it has stuck in my mind ever since, and I started my second attempt a few days ago. I used to be a hardcore literature guy, if you can believe it (my handle, which I have used since high school, is partially a Ulysses reference). Really want to get back in touch with that part of myself. I apologize to those who were anticipating a rush of productivity when I got my new laptop. But if I am the only person who does what I do (at least for the old stuff), then I have a responsibility to make this work more sustainable on my end. I cannot kill myself trying to tell their stories: not if I want to get through telling them.

-

Rashomon Tsunagoro

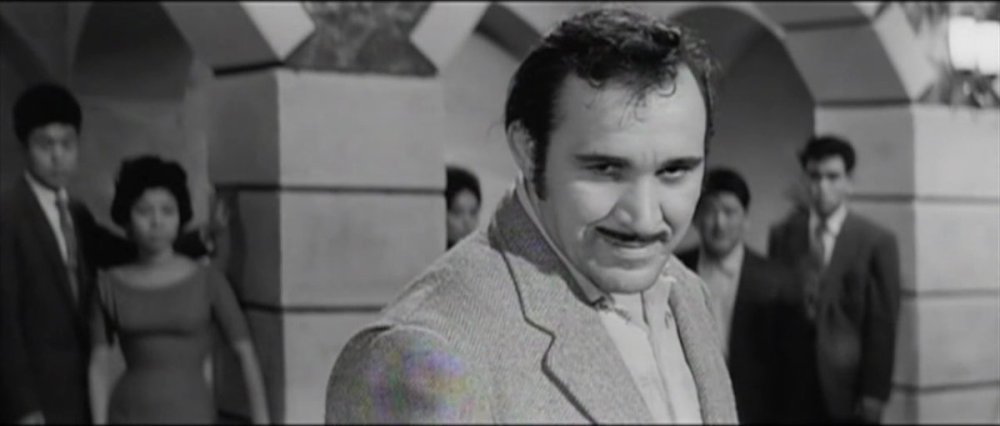

Rashomon Tsunagoro (羅生門綱五郎) Profession: Wrestler Real name: Zhuo Yiyue Professional names: Zhuo Yiyue, Niitakayama, Rashomon Tsunegoro Life: 3/5/1920-unknown Born: Taiwan Career: 1954-1957 Height/Weight: 203cm/125kg (6’8”/276lbs) Signature moves: single-leg crab Promotions: Japan Wrestling Association Titles: none The tallest man in puroresu for its first several years, Rashomon Tsunagoro is more noted now for his subsequent acting work. Standing at 6’8”, the Taiwanese Zhuo Yiyue entered sumo through the Hanago stable in 1940. First given the name Niitakayama, after the name given to Taiwan’s tallest mountain when it was a subject of Imperial Japan, Zhuo changed his name to Izuminishiki. He retired in 1946 after having stalled out at the makushita division. Eight years later, Zhuo entered pro wrestling through the JWA, and would go by various names through a four-year stint. The tallest man in puroresu until Giant Baba, for whom he has been mistaken by modern viewers, the man best remembered as Rashomon Tsunegoro was noted for his tag team with a former stablemate, the 5’6” Fujitayama. As the JWA entered its first decline, Rashomon left wrestling in late 1957. He would make a successful pivot into acting, as his frame found him steady work as a bit player in late 50s and early 60s productions. The most notable of these, certainly to Western audiences, was as a henchman in Akira Kurosawa’s classic Yojimbo. Rashomon stands out in Yojimbo.

-

Hideyuki Nagasawa

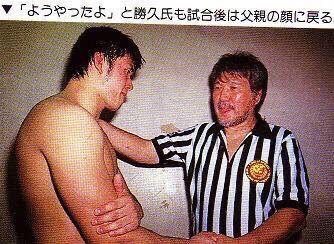

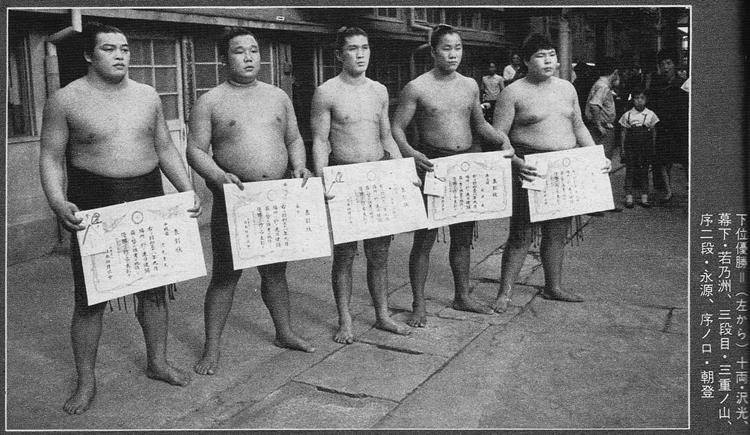

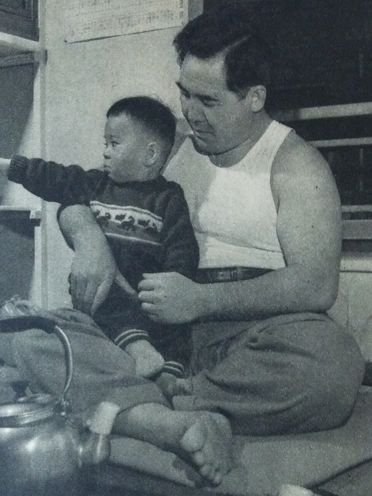

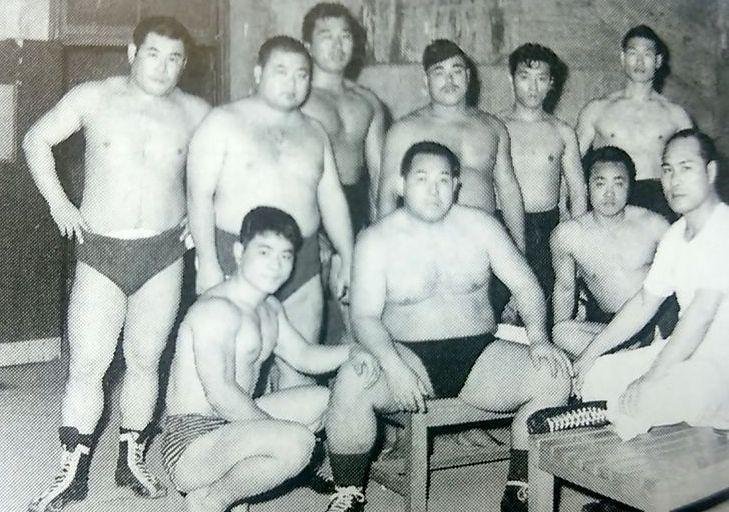

Hideyuki Nagasawa (長沢秀幸) Profession: Wrestler, Referee, Executive/Miscellaneous Real name: Hideyuki Nagasawa Professional names: Kaichi Nagasawa (長沢日一), Toranosuke Nagasawa (長沢虎之助), Hideyuki Nagasawa, Tiger Chung Lee Life: 1/2/1924-1/10/1999 Born: Osaka, Osaka, Japan Career: 1954 Height/Weight: 176cm/85kg (5’9”/187lbs) Signature moves: unknown Promotions: All Japan Pro Wrestling Association, Japan Wrestling Association, International Wrestling Enterprise Titles: none The last active Japanese wrestler to have been born in the Taisho period, Hideyuki Nagasawa never had what it took to be a top star but had a quarter-century career in and out of the ring. Nagasawa stands at far left in an AJPWA roster photo. A Dewanoumi wrestler who left sumo for the military, Hideyuki Nagasawa did not return to Tokyo when he was demobilized. Instead, he became a salaryman in Osaka who competed for a corporate sumo team, but returned to professional sport when he joined Toshio Yamaguchi and Umeyuki Kiyomigawa’s All Japan Pro Wrestling Association. He worked on the AJPWA’s shows as well as on various JWA dates through 1954. As the AJPWA collapsed in 1956, Nagasawa moved with Yamaguchi to wrestle shows out of Toshio's native Mishima. In October 1956, Nagasawa entered the Japan Weight Class tournament, a series of three interpromotional tournaments intended to delegitimize the JWA’s competitors and scout talent worth swiping. As the heavyweight bracket began at the International Stadium on October 23, Nagasawa was eliminated in the first round by eventual winner and former yokozuna Azumafuji. As the story goes, he was watching the show from the back of the venue when Rikidozan arrived and asked how he was doing. Nagasawa admitted that he was contemplating retirement for various reasons, but that if Rikidozan wanted him, he would join the JWA. Nagasawa got a call from Toyonobori, and he was working on JWA shows the following month. He would be one of five regional wrestlers hired by the JWA, alongside Michiaki Yoshimura, Kanji Higuchi, Yuichi Deguchi, and Kiyotaka Otsubo. Anecdotal evidence paints Nagasawa as a man who could handle himself. During a show in Taiwan, Yoshinosato is said to have suggested to Rikidozan that Nagasawa, instead of himself, fight a local kenpo practitioner who had challenged the JWA. Antonio Inoki and Motoyuki Kitazawa both attested to his strength. Regardless of whether Nagasawa really was as tough as some have claimed, it is clear that he did not have what it took to be a top star, even if that may have been more a function of temperament than talent. That is not to say that Nagasawa did not make valuable contributions. In fact, he was the JWA’s first head coach. The first several years of puroresu were entirely populated by wrestlers had prior experience in sumo, judo, or amateur wrestling, but not long after Nagasawa joined the JWA, those that I call the Second Generation of puroresu began to enter the company. Kitazawa praised Nagasawa as a kind man who could deal with everyone, “from new apprentices to old-timers, without dividing them”. He was also responsible for looking after foreign wrestlers, although it is unspecified as to whether Nagasawa spoke English. In March 1960, after Mammoth Suzuki infamously chickened out, Nagasawa was brought with Rikidozan on his second and last trip to Brazil. The two wrestled there for four weeks; they also met Kanji Inoki. Speaking of him, it was once reported that Inoki’s first match billed as Antonio was against Kintaro Oki on November 7, 1962. However, a recent revised edition of Team Full Swing’s book of complete Inoki match results corrected this: it was against Nagasawa two days later. By the mid-sixties, when Otsubo had taken over as head coach, Nagasawa rarely wrestled and was often seen dismantling the ring at the end of shows. Kitazawa recalls that this bothered him, and that he had tried to help his senior, but that Nagasawa said it was okay, and that it was his job. In 1966, in the corporate restructuring after Toyonobori’s acrimonious departure, Nagasawa was named a director of the JWA alongside Giant Baba. He would stay with the JWA until the end, working as a referee. After that, he got a job with the IWE’s materials department. Like others originally hired for the IWE’s ring crew, namely Ichimasa Wakamatsu and Hiromichi Fuyuki, Nagasawa would find himself back in the ring. By this point, Nagasawa was the last active Japanese wrestler born in the Taisho period. At first, he wrestled under a mask as Tiger Chung Lee, but he would wrestle as himself for most of this stint back in the ring, which lasted until a match against Tsutomu Yonemura in October 1976. After this, Nagasawa remained with the company until shortly before its demise. He died in 1999.

-

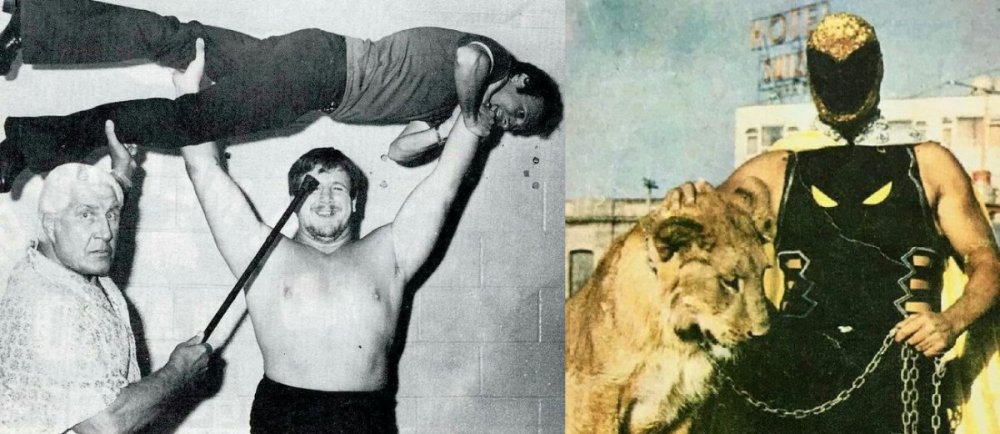

Toshio Yamaguchi

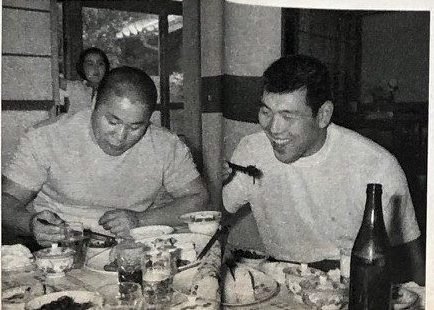

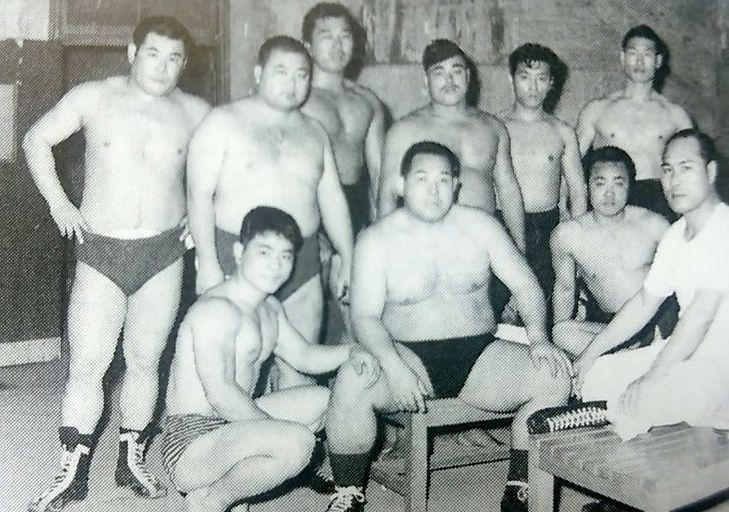

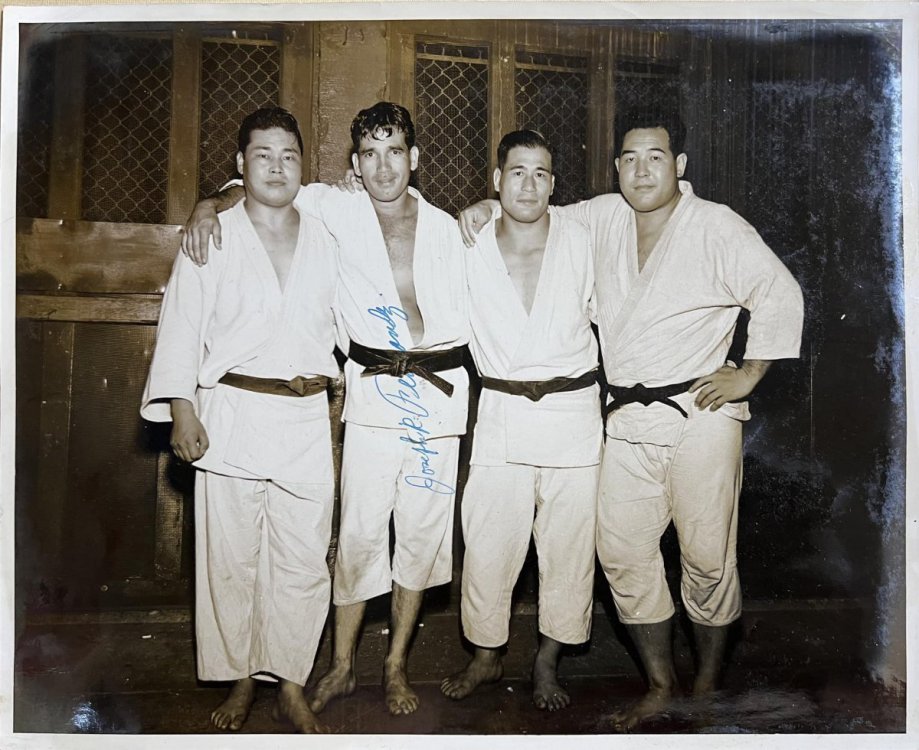

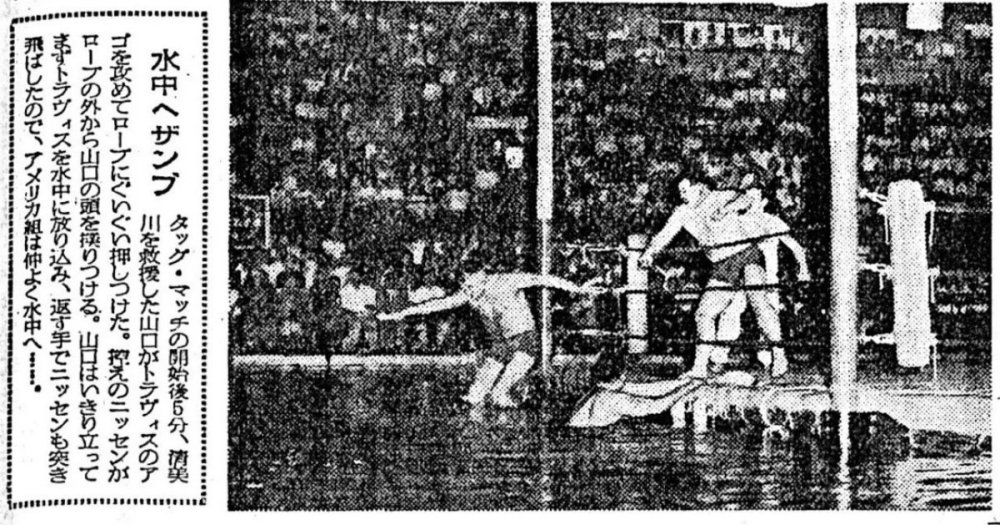

Toshio Yamaguchi (山口利夫) Profession: Wrestler, Promoter Real name: Toshio Yamaguchi Professional names: unknown Life: 7/28/1914-4/1/1986 Born: Mishima, Shizuoka, Japan Career: 1951-1958 Height/Weight: 180cm/115kg (5’11”/254lbs.) Signature moves: tackle Promotions: All Japan Pro Wrestling Association/Yamaguchi Dojo Titles: none Now too often forgotten, Toshio Yamaguchi was a puroresu pioneer whose All Japan Pro Wrestling Association was a significant regional promotion. Yamaguchi (right) in Hawaii in 1951. Masahiko Kimura is right next to him. (Image credit: Facebook user Ryosuke Ratel Nasa) Before the war, Toshio Yamaguchi made his name as a skilled judoka, first as a member of Waseda University’s club, and then as an employee of the South Manchuria Railway, where he was nicknamed the Manchurian Tiger. He entered the original incarnation of the All-Japan Judo Championships four times between 1935 and 1941, notching third and second-place in his division in 1936 and 1937. In 1939, he made a brief switch into sumo and entered the Dewanoumi stable. Due to Yamaguchi’s pedigree, he was initially allowed to compete in the makushita division as a makushita tsukedashi, but a poor showing in his debut tournament led him to be demoted. After a second tournament, in which he competed as Daigoro Yamaguchi, he was drafted and forced to retire. I don’t have anything on Yamaguchi for the rest of the forties, but in 1950, he was a founding member of the International Judo Association. I plan to someday cover the IJA, often called Pro Judo for short, in detail for a PWO thread or blog post. But to summarize, it was a brief yet significant antecedent to puroresu. As Kodokan shifted its strategy to promote judo as an amateur sport—a desperate measure to survive under American occupation, and to get judo back into the phys-ed curriculum—Tatsukuma Ushijima sought to pave another road on which impoverished martial artists could make a living as sports-entertainers. IJA events, which began in April 1950, offered judo matches with loose rules. Draws and decision wins were out: joint techniques and bodyslams, in. Entertainers like Keiko Tsushima, who you may know from Seven Samurai, and Koji Tsuruta also sang and danced in segments of these shows. Behind the legendary Masahiko Kimura, Yamaguchi was the IJA’s second strongest judoka. That June, the two signed a contract to work in Honolulu in October, but a lawsuit from the IJA kept them in Japan until the following year. By that point, though, the Association’s support from construction company Takagi Corporation had been withdrawn, and it hadn’t held a show in two months. Kimura went in January to hold a seminar at Hawaii University. When Yamaguchi arrived the following month, the two appeared on shows promoted by the Matsuo brothers while being trained in pro wrestling by their manager, Rubberman Higami. After they were finished with the Matsuo contract, Kimura and Yamaguchi began work for promoter Al Karasick, who would spearhead American pro wrestling’s export into Japan through the Torii Oasis Shriners Club tour of the late year. Over the next year, Yamaguchi and Kimura wrestled in North America and Mexico, as well as compete in their original sport on a famous trip to Brazil. In April 1952, Yamaguchi even teamed up with Rikidozan on a California show. Back in Japan, both Yamaguchi and Kimura participated in Osaka juken shows, which pitted judoka against boxers of foreign descent. These had a decades-long history, and had most notably been held to promote boxing in the 1920s, but the juken revival was the responsibility of future joshi promoter Morie Nakamura. In July 1953, news of the formation of the Japan Wrestling Association triggered further development. On July 18, less than three weeks after the JWA had been established, a juken show at the Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium, which was a charity event for Kitakyushu flood victims, was headlined by a judo vs sumo match in which Yamaguchi fought the retired rikishi Umeyuki Kiyomigawa. According to a column called “The Birth of Kansai Pro Wrestling”, written by former Mainichi Shimbun sports head Katsuhisa Tanaguchi for Hiroshi Tazuhama’s 1975 book 20 Years of Japanese Pro Wrestling, the origins of the All Japan Pro Wrestling Association laid in a translation of the Mainichi article on the show. It piqued the interest of a GI stationed in Osaka at the time, who approached Yamaguchi and claimed that he was the manager of a wrestler named Bulldog Butcher who wanted to wrestle him. (In reality, Butcher was his commanding officer.) Yamaguchi was initially uninterested, but the proposal caught the ear of Shotaru Matsuyama, the head of a local yakuza gang called the Sarae-gumi. Matsuyama went to Mainichi to make a formal request to hold this show, and this led to the formation of the All Japan Pro Wrestling Association. (Yamaguchi had first suggested a regional name, like Kansai or West Japan.) The AJPWA's first show was at the Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium on December 8, 1953. Two months later, they beat the JWA to the punch with puroresu's first television broadcast. On February 6 and 7, 1954, they booked the OPG for two well-drawing shows sponsored by Mainichi as well as the Manaslu mountain-climbing team. (Hey, whoever wants to help you promote your show.) These shows were broadcast live in the Kansai and Tokai regions as an experiment by NHK. Twelve days later, Yamaguchi began work on the JWA’s first tour alongside others in his organization. The AJPWA resumed work in April, although records of its shows are inadequate. When Kimura challenged Rikidozan in the paper that autumn, Yamaguchi threw his hat into the ring by stating his challenge to whichever man won. On December 22 at the Kuramae Kokukigan, on a show where AJPWA wrestler Noburo Ichikawa was brutally beaten by Junzo Yoshinosato, Rikidozan shot on Kimura in the main event. On January 26, a JWA-AJPWA joint show saw Yamaguchi challenge for the Japanese Heavyweight title. Unlike with Kimura, Yamaguchi's title shot was all business, and he even lost two falls to the champion, albeit by countout. This was the last heavyweight title match between two natives for 18 years, until Rusher Kimura challenged Strong Kobayashi for the IWA World Heavyweight title in July 1973. The first of the AJPWA's famous pool shows. While it was completely dependent on American servicemen for opponents—the only foreign professional wrestler who worked with them was PY Chang, the future Tojo Yamamoto—the Association distinguished itself with gimmicks. The AJPWA was puroresu's first, and for decades, only intergender promotion, and also featured midget wrestling. The Association also held shows at Osaka's Ogimachi Pool, starting with a televised one on September 25, 1954. While they did not invent the wrestling show-in-water, which had roots in the 1930s, the AJPWA's Ogimachi shows were the first such events in puroresu, and they predated FMW's revival of the gimmick by over thirty years. Trouble came in 1956. The same year that Rikidozan’s patron Shinsaku Nitta died, the first omen of a three-year decline that nearly killed puroresu, Matsuyama fell ill and withdrew his AJPWA support. Yamaguchi and his faithful, which did not include Kiyomigawa, left Osaka that summer for Toshio's hometown of Mishima, where they ran shows in poverty under the Yamaguchi Dojo banner. (The Osaka market would be filled by the short-lived Toa Pro Wrestling, formed by Korean-born Daidozan.) That autumn, Yamaguchi had his last significant matches in the Japan Weight Class tournament. Held by the JWA to delegitimize its regional competitors and scout talent that were worth poaching, the tournament saw Yamaguchi advance to the finals of the heavyweight division, which was meant to set up a Rikidozan title defense that was never booked. After their first match went to a draw, Yamaguchi lost the final by countout to former yokozuna Azumafuji. After this, four of his wrestlers were raided by the JWA: Michiaki Yoshimura, Kanji Higuchi, Yuichi Deguchi, and Hideyuki Nagasawa. According to Showa Puroresu, Yamaguchi Dojo was dissolved in September 1957. Yamaguchi retired the following year, holding two last Osaka pool shows on May 31 and June 1 with guests ranging from Yoshimura to Kimura. He died in his hometown of heart failure in 1986. Yamaguchi sits with the AJPWA roster.

-

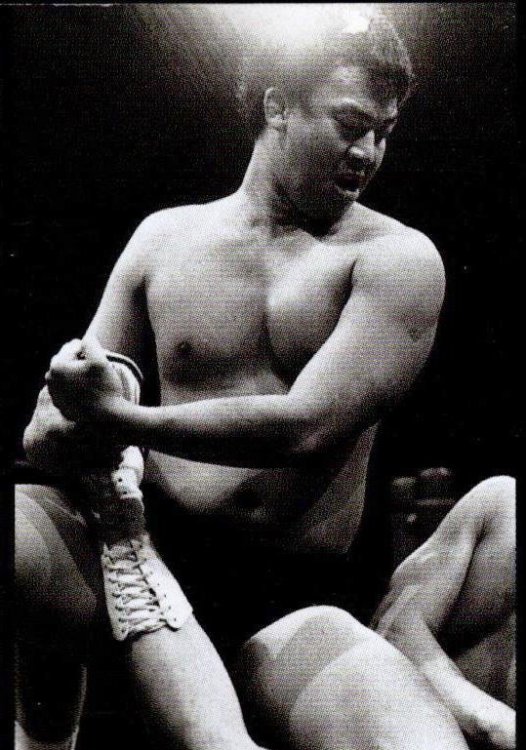

Kiyotaka Otsubo

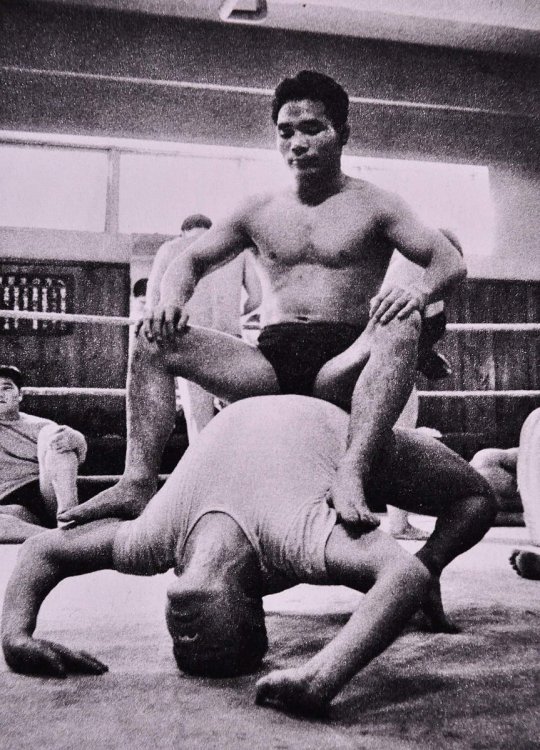

Kiyotaka Otsubo (大坪清隆) Profession: Wrestler, Trainer Real name: Kiyotaka Otsubo Professional names: Kiyotaka Otsubo, Hishakaku Ootsubo Life: 7/10/1927-7/29/1982 Born: Tottori or Tokyo, Japan (sources vary) Career: mid 1950s-1971 Height/Weight: 170cm/93kg (5’7”/205lbs.) Signature moves: Boston crab Promotions: International Pro Wrestling (Kimura), Japan Wrestling Association Titles: none Kiyotaka Otsubo was most important as an early puroresu trainer. Otsubo sits on Antonio Inoki as he performs a neck bridge. [THIS PROFILE IS BEING REWRITTEN.]

-

Toshio Komatsu

Toshio Komatsu (小松敏男) Profession: Referee, Announcer, Executive (Sales) Real name: Toshio Komatsu Professional names: not applicable Life: 3/3/1925-unknown Born: Kochi, Shikoku, Japan Career: 1954-1966 Promotions: Japan Wrestling Association, Tokyo Pro Wrestling, All Japan Women’s Pro-Wrestling (as executive) One of the JWA’s first referees, Toshio Komatsu transitioned into announcing in the early sixties before retiring to become a promoter. The fourth of eight children born to a Kochi realtor, Toshio Sento took the family name Komatsu when he entered school. Like just about all of his family, Toshio was a sumo fan, and competed in local tournaments alongside his eldest brother behind their mother’s back. Upon graduating junior high, he moved to Tokyo against his mother’s will to join a stable. In March 1941, he joined the Nishonoseki stable despite being far under the required weight at the time: a traditional measurement equivalent to about 73kg (160lbs). Komatsu claimed that he failed the first measurement, but that Oyama Oyakata had told him to try again, and that Oyama then recorded what the scale had measured at the moment he had jumped onto it. Sumo only had two tournaments a year at this time, so Komatsu had little experience before he was drafted. In September 1942, he was sent to the Malay peninsula as a private in the 44th Industry Regiment, and served as a light machine gunner. He did not see any battles himself, but he may have narrowly avoided death. An order to report for a cadet examination had separated him from his platoon just before they set out to attack a group of “communist bandits” in Johor Bahru, who had prepared to fire at them from the opposite bank. After the war, Komatsu remained in Malay as a laborer until he was demobilized in December 1947. He had given up hope of entering sumo shape again; as a matter of fact, a rumor had spread amongst his former stablemates that he had been killed on his way home, in a Korean riot. Toshio first found a job in Kochi, where he had first set foot back home, but after six months, he moved to Kyushu, where he worked in a coal mine for two years. Upon his return to Kochi, an acquaintance from Yokohama reintroduced Komatsu to his former stablemate Rikidozan. By this time, Rikidozan had retired from sumo to work for the construction company of patron Shinsaku Nitta, for which Komatsu would also work. Komatsu was in attendance when Rikidozan wrestled his first match against Bobby Bruns: “Riki-san was wearing a yukata with a large lobster pattern dyed on it as a gown, and within five minutes his belly started to ripple, which kept me on the edge of my seat.” When Rikidozan left for Hawaii in 1952, Komatsu was the one who babysat Yoshihiro and Mitsuo Momota. Komatsu continued to work for Nitta Kensetsu for the rest of the fifties, as he spent six years building pavilions for fireworks shows in the Ryogoku river festival. He even hired trainees at the Riki Gym, led by a young Hisashi Shinma, to serve as nightwatchmen and prevent theft. However, Rikidozan “forcibly recruited” Toshio in the spring of 1955. He was initially promised a job as a clerk, but second referee Yoshio Kyushuzan was weary of officiating all but the last two matches of each show. Komatsu became the JWA’s undercard referee. Five years later, he was forced to take the job that would make him famous. In the JWA’s early years, they had hired a freelance announcer, one Mr. Sakae, to call most matches. This ended on May 11, 1960, when Sakae received a telegram to come home. Rikidozan made Komatsu take his place on the spot. Komatsu modeled his calls after Naoyoshi Akutsu, a boxing announcer that the JWA had borrowed for big matches. It was rough at first. When the JWA began broadcasting weekly at the Riki Sports Palace, Toshio thought he looked “as if his face was on fire” and began practicing with a mirror. He also made various mistakes, such as calling Mr. Atomic “Mr. X” and announcing Kiyotaka Otsubo as “Tsubo-yan”. He claimed that he once made the latter error three times in a row, and if the translation is correct, Otsubo mooned him in response. Komatsu's voice was not pretty, but it had power, and the “Komatsu bushi” became the most iconic puroresu call for decades. He appeared in commercials for Mitsubishi appliances where he called product models “in the red and blue corners”. Komatsu was the only announcer to appear in commercials until Kero Tanaka in the 1980s. Nowadays, his greatest legacy is calling the last surviving Rikidozan match: against the Destroyer, on December 2, 1963. Komatsu continued as an announcer until a shift to the sales department in 1965, upon which he was replaced by Nagaaki Shinohara. When the Tokyo Metropolitan Police cracked down on the JWA, they did not just pressure the top shareholders with criminal ties to resign. They also forced the company to purge all but seven of the local promoters that they had sold shows to. The JWA could no longer run many of the buildings that they had built their circuit on, and the department scrambled to find new connections. Komatsu flew back to Shikoku Island, where a close friend of his brother was the head of the Kochi Shimbun newspaper’s sports department. Through that connection, he won the support of the island’s newspapers. Despite this success, Komatsu left the JWA that summer. He was unable to keep up with the sales quotas that the top executives had enacted “only out of immediate greed”. (I suspect this was a dig at Kokichi Endo.) After that, Toshio spent the next decade as an independent promoter, although he briefly returned to announcing for Tokyo Pro Wrestling. Komatsu spent the first two years in Tokyo, where he organized jazz and group sounds concerts. He claimed that he had promoted concerts by nearly every major band in the latter genre, “except the Spiders”, but his calls on other promoters to help him build a tour circuit were abandoned by his would-be partners. After cleaning up that mess, Komatsu eventually returned to the wrestling business and settled in Kochi: “[…] I knew I could not betray [wrestling], and it eventually helped me to stabilize myself mentally and financially.” The 1979 Monthly Pro feature reports that Komatsu refused to gouge ticket prices on his shows; the best seats were always six thousand yen, and every seat below sat at a fixed rate. In 1972, he was one of the first promoters to give New Japan Pro-Wrestling any proper support. Eventually, his reliability got him a job with the Matsunaga brothers, who entrusted him with setting up AJW’s western tours. On January 11, 1980, Komatsu picked up the house mic one last time for Jumbo Tsuruta’s NWA United National title defense against Billy Robinson. Komatsu attends AJW's February 1979 Budokan show.

-

The Big Puroresu Profile Index

UPDATES, FEBRUARY 2023 Generally, I have only made minor adjustments and additions to profiles in the six months since I posted my last proper update. The exception was a major expansion of Mammoth Suzuki's profile. But it was only in February that I added any new profiles. Also, this month saw the debut of joshi profiles, courtesy of the Sensational, Intelligent @Noah's_Savior! New Profiles Donald Takeshi (Wrestler, JWA/NJPW) Haruka Eigen (Wrestler/Executive, Tokyo Pro/JWA/NJPW/JPW/AJPW/NOAH) Haruko Ogawa (Wrestler, AJW) Hitoshi Yoshida (Executive, AJW) Junzo Yoshinosato (Wrestler/Broadcaster/Executive, JWA/IWE) Katsuhisa Shibata (Wrestler/Referee, Tokyo Pro/JWA/NJPW) Kyoko Okada (Wrestler, AJW) Maki Ueda (Wrestler, AJW) Motoyuki Kitazawa (Wrestler/Referee, JWA/Tokyo Pro/NJPW/UWF) Oscar Ichijou (Wrestler, AJW) Peggy Kuroda (Wrestler, AJW) Yusuf Turk (Wrestler/Referee/Executive, AJPWA/JWA/NJPW)

-

Junzo Yoshinosato

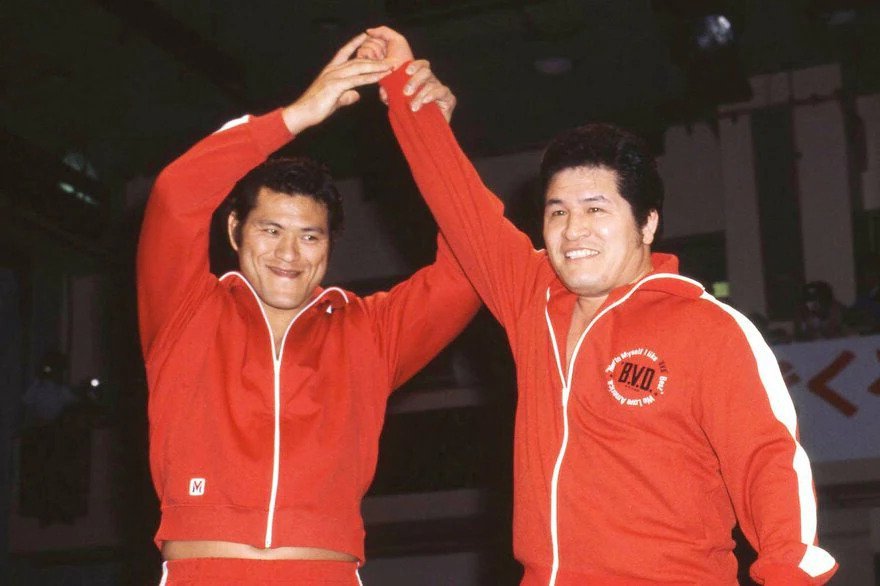

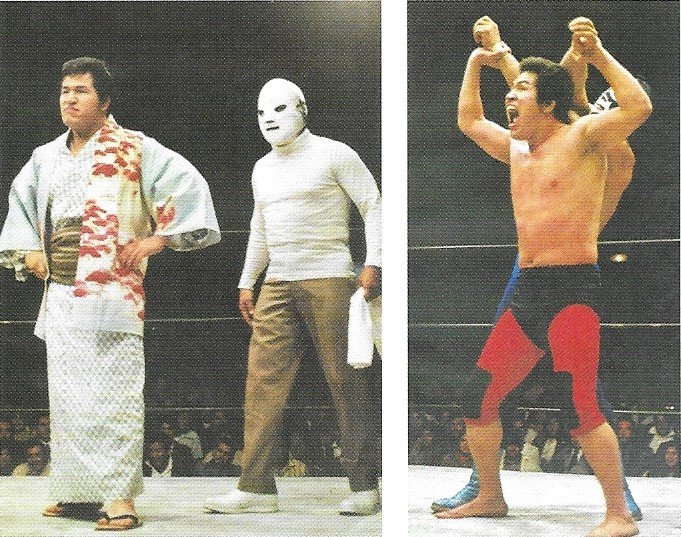

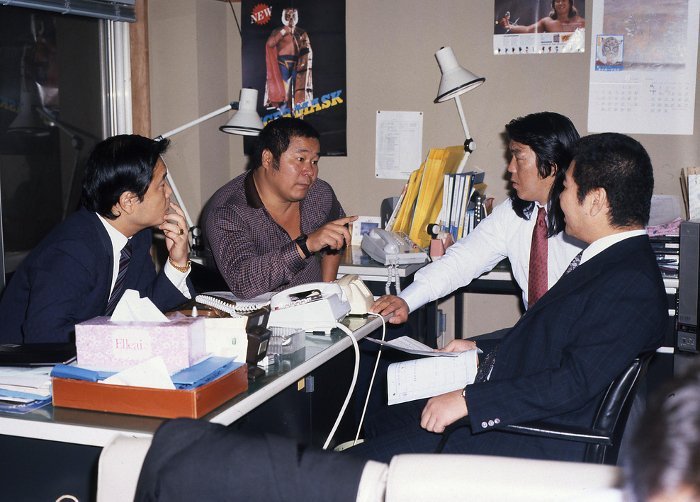

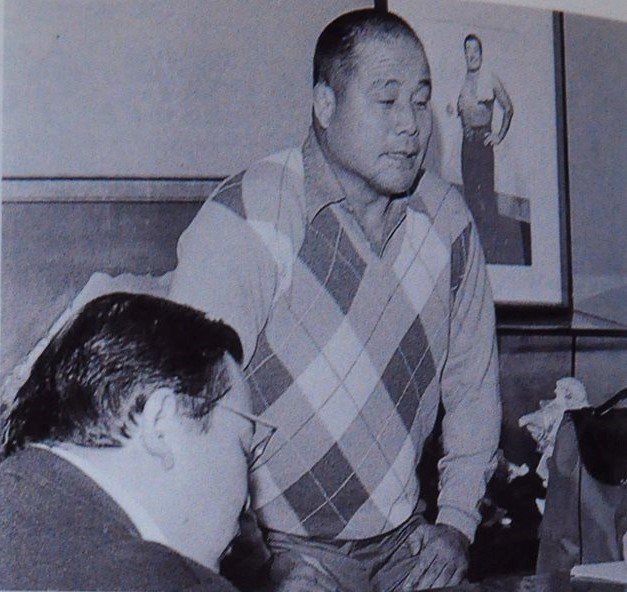

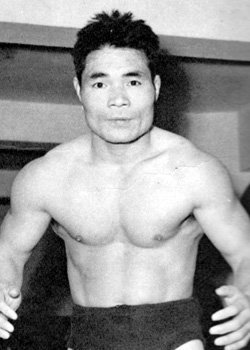

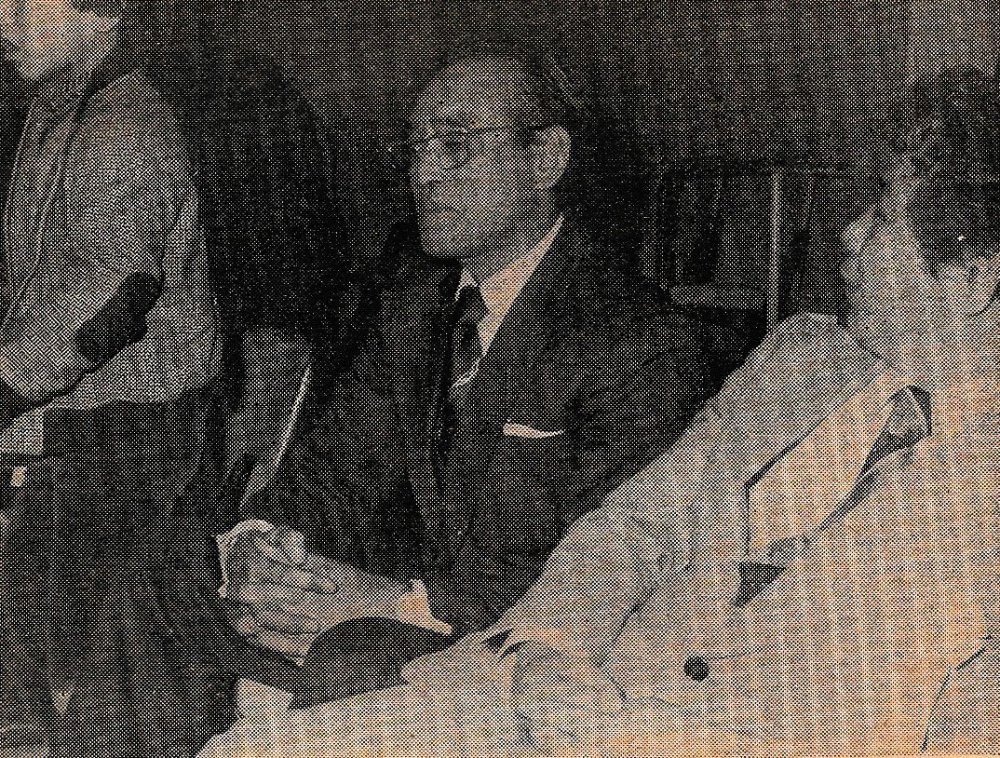

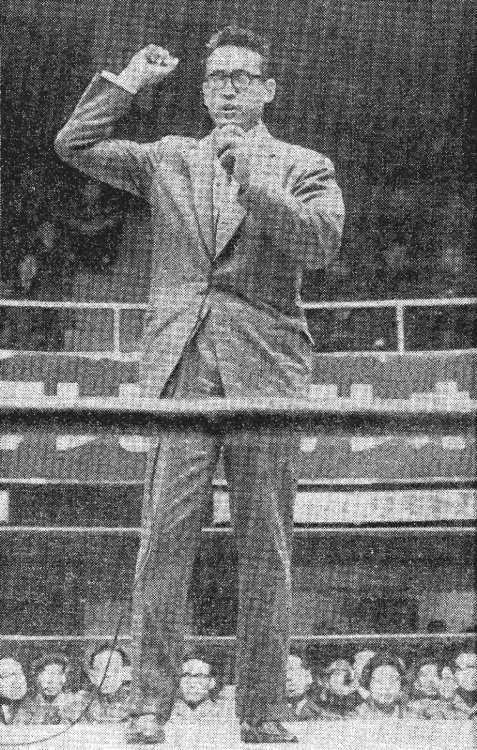

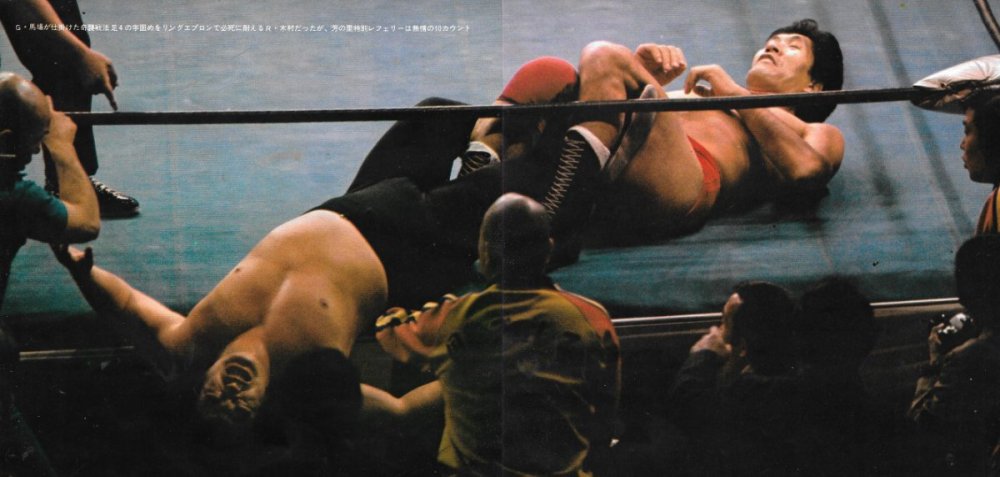

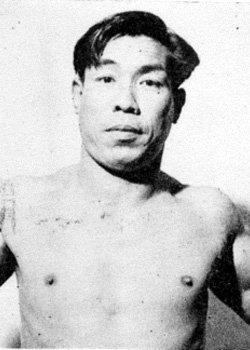

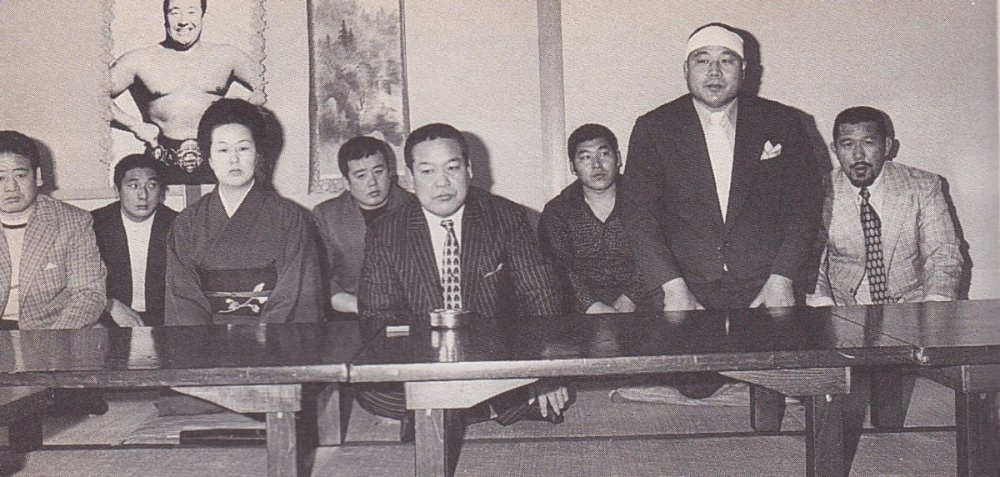

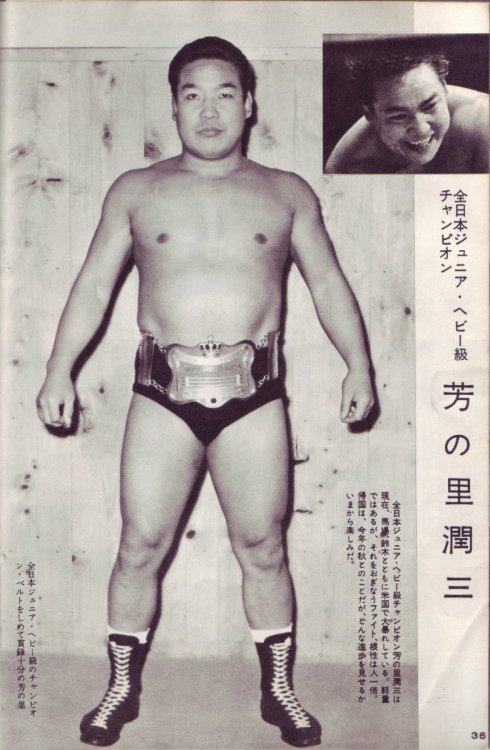

Junzo Yoshinosato (芳の里淳三) Profession: Wrestler, Executive, Commentator (Color) Real name: Junzo Hasegawa (長谷川淳三) Professional names: Junzo Yoshinosato, Yoshino Sato Life: 9/27/1928-1/19/1999 Born: Ichinomiya, Chiba, Japan Career: 1954-1973 Height/Weight: 174cm/84kg (5’9”/185lbs.) Signature moves: Small package Promotions: Japan Wrestling Association, International Wrestling Enterprise (as commentator) Titles: Japanese Light Heavyweight [JWA] (1x), Japanese Junior Heavyweight [JWA] (1x) Junzo Hasegawa, or Yoshinosato, carved out a niche as one of puroresu’s earliest junior heavyweights, but for better or worse, his legacy is defined by his career as a JWA executive and its last president. Yoshinosato during his sumo career. The fourth son of a farmer-fisherman, Junzo Hasegawa was an athletic child. He aspired to enter sumo, and did so despite his small size by getting in through wrestler Kamikaze Shoichi. Hasegawa joined the Nishonoseki stable, for which he debuted under his family name in January 1944. As this was the twilight of the Pacific War, Hasegawa was among a group of fellow Nishonoseki wrestlers, led by their master Tamanoumi, who worked hard labor for food in an Amagasaki munitions factory. (Tamanoumi would be charged as a war criminal for this, and his reputation with the Japan Sumo Association never recovered.) When the Great Tokyo Air Raid reduced Nishonoseki’s headquarters to rubble, the stable rented a room at the Shinmonji Temple, where they remained until 1950. Hasegawa devoted himself to training, and in 1947, he received his first shikona: Kamiwaka, derived from the rikishi who he had idolized in his youth. Despite his frame, Junzo became noted for his technical skill and a particular prowess at the beltless underarm throw known as sukuinage. In 1949, as the sumo schedule returned to three tournaments, Kamiwaka was promoted to the second-highest division, juryo. Another promotion to makushita followed at the start of the decade, but he struggled and was demoted in 1951. It was after this knock down back to juryo that he debuted the shikona that would stick: Yoshinosato Yasuhide. Yoshinosato was not among those that started puroresu, but he made an early career change. Junzo had become disillusioned with Nishonoseki and its turmoil. His beloved Kamikaze was retiring to become a sumo commentator. Tamanoumi had passed the stable down to Saganohana in 1952, and his policy of encouraging his makuuchi to take on disciples had led to the departures of Ōnoumi and future yokozuna Wakanohana. Despite all of this, Yoshinosato was held down in juryo. Despite notching one of the strongest showings of his career in the spring 1954 tournament, where he went 11-4, he retired afterwards. Noburo Ichikawa, the victim of puroresu’s first documented shoot incident. Yoshinosato went to his former senior and join the JWA. Depending on the version of the story, he either had one day of training before his debut, which was against Teizo Watanabe on September 10 in Osaka, or first met Rikidozan at the show and had been booked on the spot. Either way, it is the fastest turnaround time in puroresu history. Three months later, he worked on the December 22, 1954 show at the Kuramae Kokugikan. This show is well known for the main event, in which Rikidozan shot on Masahiko Kimura. Far less known, at least in the West, is that it wasn’t the only shoot incident on the card, or even the most upsetting. At what the Toshiyo Masuda serial Why Didn’t Masahiko Kimura Kill Rikidozan? alleges was his boss’s order, Yoshinosato beat Noburo Ichikawa, a 38-year-old judoka who had joined Toshio Yamaguchi’s All Japan Pro Wrestling Association, into unconsciousness with “several dozen” strikes. Masuda’s serial claims that Ichikawa suffered neurological damage from this assault and died in 1967. In October 1956, Yoshinosato entered the light heavyweight bracket of the interpromotional Japanese Weight Division Championship tournaments, which were a means for Rikidozan to delegitimize his regional competition and scout talent worth poaching from them. After wins against Toa Pro Wrestling’s Genji Umehara, fellow JWA member Toshikazu Higa, and Asia Pro Wrestling’s Kiyotaka Otsubo, Yoshinosato faced his coworker Isao Yoshiwara to crown the first Japanese light heavyweight champion. At the Ryogoku International Stadium on October 23, Junzo won two straight falls, first with an abdominal stretch and then with an armbar. On November 30, Yoshinosato wrestled a champion vs champion match against junior heavyweight champ Surugaumi, which went to a draw. While Surugaumi’s title reign ended to Michiaki Yoshimura the following year, Yoshinosato held onto his belt for the rest of the decade. Like the junior title, which was also only contended between native talent, the light heavyweight belt was essentially abandoned after the turbulence of the late fifties showed that the JWA could not draw with anything but Rikidozan versus foreigners. In November 1958, Yoshinosato accompanied Rikidozan on his first trip to Brazil, working shows with him for a month as JWA shows drew all-time lows without their ace. By the summer of 1960, though, Yoshimura was ready for a promotion to the heavyweight division. Yoshinosato challenged him for the junior title, and a match was booked for the Taito Ward Gymnasium on August 19. While three hours of Yoshimura footage circulates on tape, little of Yoshinosato’s work is known to survive. This means that our only knowledge of his style in the ring comes from written coverage of the time. Fortunately, the Showa Puroresu zine reproduces an evocative report of this match from Pro Wrestling & Boxing magazine. It describes the 61-minute draw, which was officiated by none other than Rikidozan, as a lively, then grueling affair. The smaller Yoshinosato is described as a scrappy, unscrupulous challenger. The title did not properly change hands, but with Yoshimura’s promotion, Yoshinosato was awarded the junior title by default. His light heavyweight title was won by Isao Yoshiwara in a subsequent tournament. Yoshinosato left for the United States alongside Shohei Baba and Yukio Suzuki in June 1961. Although he worked for NWA Hollywood and in the Northeast like them, his two years abroad were most notable for a stint as a stock Japanese heel, Yoshino Sato, alongside Tojo Yamamoto in Tennessee. This would influence him when he returned home, as he took to wearing “rice-field” tights while using his geta (wooden sandals) as a weapon. He returned in September 1963, just months before Rikidozan's death. When that came on December 15, he got a promotion. Yoshinosato was one of the four wrestlers rapidly promoted to an executive position, alongside Toyonobori, Kokichi Endo, and Yoshimura. At first, they were named directors, while widow Keiko Momota assumed a figurehead position as company president. Yoshinosato, Toyonobori, Endo, and Yoshimura in a famous photoshoot after Rikidozan’s death. This was a deeply turbulent period in puroresu, as just five months after Rikidozan’s death, the death of commissioner Bamboku Ono dealt almost as severe a blow as that had. Without the flagrantly yakuza-tainted politician to act as a buffer against law enforcement, the Tokyo Metropolitan Police set their sights on the JWA as part of the first Operation Summit. The top shareholders were ultranationalist fixer Yoshio Kodama and top yakuza godfathers Kazuo Taoka and Hisayuki Machii. Not only did they step down in 1965, as Keiko and managing director Hiroshi Iwata did the same, but the JWA was also forced to cut ties with all but seven of the local promoters they sold shows to. Toyonobori was promoted to president, with Yoshinosato as his VP. Junzo was forced to pick up his slack, as Toyonobori was less interested in doing his job than in betting on horses with the company safe as his piggy bank. Yoshinosato continued to wrestle in this period; in fact, footage from a May 1964 tag match broadcast on G+’s 2019 JWA program, as seen in this screencap, is the only surviving tape of him that I am aware of. (Unfortunately, I have not found a copy of this as of writing.) In August 1965, he wrestled his last significant matches abroad. Kim Il, or Kintaro Oki, held his first South Korean tour with the support of the JWA and the resentful cooperation of native wrestler-promoter Jang Yeong-chol. Kim defeated Yoshinosato in the final match of an eight-man tournament to be crowned the first Far East Heavyweight champion. Hasegawa and Endo with Sam Muchnick in August 1967. As the year came to a close, Toyonobori fell out of favor with his fellow executives and left. When this was publicly acknowledged in early 1966, Yoshinosato was named the new JWA president. While he received the nickname Geta President, he wouldn’t be attacking people with his sandals much longer, as Hasegawa scaled back his appearances until wrestling a final match on August 1, 1967. The first year of his presidency saw the emergence of two competitors, Toyonobori’s Tokyo Pro and Yoshiwara’s Kokusai (IWE). By the time of his last match, though, Tokyo Pro had fallen apart and Antonio Inoki had returned to the JWA. Hasegawa steered the company during its second golden age. In the year to come, Baba and Inoki begin their run as Japan’s most iconic tag team, while the JWA went to war against Kokusai. The competition led the company’s Nippon Television program to be upgraded from biweekly to weekly, with the extra broadcast money in tow. They went even beyond that in 1969, when Endo successfully maneuvered his way into getting a second network deal with NET TV. Unfortunately, this momentum was enough to sustain the good times forever. Suspicions of embezzlement accumulated as the seventies began, on top of a generally arrogant attitude towards the public and press and a lack of research on the foreigners they invited. (In a particularly notorious instance, the second NWA Tag Team League tournament lost a top gaikokujin halfway through the tour, as Cowboy Frankie Laine—the only returning entrant from the previous year—was deported for sexual assault.) As Hasegawa himself admitted later, he had never received the education to properly run a business at this scale and had worked most effectively in middle management. While he can absolutely be criticized for his incompetence, modern testimonies have suggested that subsequent depictions of his corruption and character were somewhat distorted. (One example was Mystery of the Orient: Kabuki, the final serial in Ikki Kajiwara’s Pro Wrestling Superstar Retsuden manga, which depicted Hasegawa taking money from the safe, as Toyonobori had, to drink in Ginza.) Whatever the case, the years of mismanagement culminated in the “phantom coup” of late 1971. While the most corrupt of the executive troika, Kokichi Endo, was successfully pressured to resign from his executive position, the managerial reforms fizzled out after Inoki and auditor Akimasa Kimura’s subsequent attempt to surreptitiously promote themselves to the top of the company. It was this final era of the JWA that set Hasegawa’s legacy as a once successful, but ultimately incompetent and doomed promoter. With Inoki's dismissal, NET heavily pressured the company to allow them to broadcast Baba matches and restore their ratings. Baba was contractually exclusive to NTV and personally loyal to them, but Hasegawa decided to disregard that and force Baba to work on World Pro Wrestling. This led the company to lose both NTV program Mitsubishi Diamond Hour and Baba himself, as NTV sent feelers to Baba to head a new promotion, and Baba left the JWA that summer. The JWA lasted until the spring of 1973, held afloat by the NET deal that lasted through the end of the fiscal year, before it held a small set of shows afterward with personal funds. In its final months, Hasegawa again showed his failure as an executive. In the last months of 1972, NET arranged a deal where Inoki’s independent, debt-ridden New Japan Pro-Wrestling would merge with the JWA in April 1973. This could have saved the company, and it was put in motion as Inoki and Sakaguchi held a press conference in February. However, most had not signed contracts to NET when Oki came back from Korea and rallied most of the company to refuse this merger. Where a truly capable leader would have done whatever was necessary to make this deal go through, Hasegawa just went with Oki and sealed his legacy forever. That spring, Hasegawa worked out a deal through Keiko Momota, now a director of All Japan Pro Wrestling, to have his remaining talent merge with the company. In Oki’s words, they were coming back to Rikidozan. Hasegawa (front, center) at the press conference where the JWA announced its death by AJPW merger. The man once known as Yoshinosato spent several more years involved in the business in some capacity. He was allowed to retain his membership on the NWA board as a condition of the AJPW merger. While he voted against New Japan’s membership in 1973 and 1974, he worked with the company for some months afterward, lending credibility to Inoki’s strategy to market himself as the best in Japan and blow smoke over a Baba match that would never happen. According to Shigeo Kado, Hasegawa had planned to loan the JWA’s World Big League trophy to New Japan for the 2nd World League tournament in 1975. However, as Kado claimed, he fell out with the company that spring when he was offended that they sent an executive, and not Inoki himself, to his house to discuss the matter. He instead lent the trophy to AJPW for their Open League tournament that December. In March 1976, All Japan leveraged his credibility by having him tag along on the South Korean show where the All Asia Tag Team titles were revived. He served as a color commentator on second IWE program International Pro Wrestling Hour and can be heard calling Mighty Inoue's IWA title victory against Billy Graham in October 1974. Yoshinosato served as the guest referee for the famous March 28, 1976 match between Jumbo Tsuruta and Rusher Kimura. Two years later, he refereed the February 1978 match between Baba and Kimura, with his dubious officiating blamed for one of the most humiliating finishes in the history of puroresu. (In fact, it is quite likely that Yoshinosato had suggested that finish himself, as it had been used five years earlier in one of the JWA's final main events.) I do not know much about what Hasegawa was up to after this point, until the last years of his life. In 1996, the Rikidozan OB alumni association was formed, and he was named its chairman. According to Dave Meltzer’s obituary, the final show Hasegawa promoted was a benefit for the now-paraplegic Umanosuke Ueda. After suffering a stroke in March 1998, Hasegawa died in Yokohama of cardiac arrest on January 19, 1999.

-

Yusuf Turk

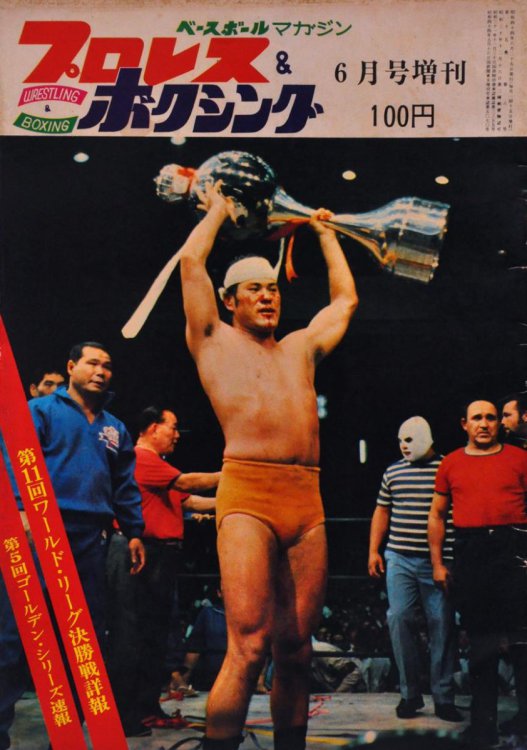

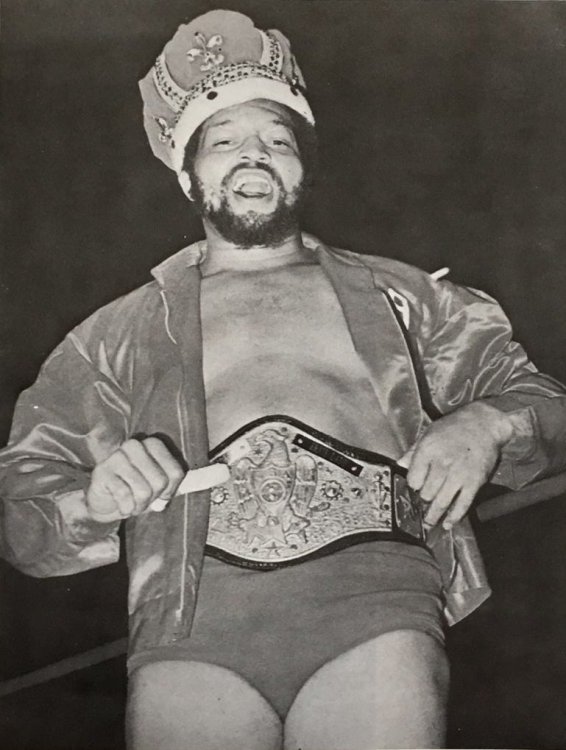

Yusuf Turk (ユセフ・トルコ) Profession: Wrestler, Referee, Executive Real name: Yusuf Omar Professional names: Killer Mike Yusuf, Yusuf Turk Life: 5/23/1931-10/18/2013 Born: Toyohara (now Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk), Sakhalin Career: 1954-1973 Height/Weight: 173cm/90kg (5’8”/198lbs.) Signature moves: surfboard stretch, flying knee drop Promotions: Japan Wrestling Association, New Japan Pro-Wrestling Titles: none One of puroresu’s earliest comic wrestlers and then a referee and booker, Yusuf Turk was an important figure in the ascension of Antonio Inoki, even if his relationship with the promotion he helped found was a turbulent one. The half-Japanese son of a Turkish trader, Yusuf Omar was born in Toyohara, then the capital of the southern, Japanese-held half of Russia’s largest island, Sakhalin. In 1938, the family moved to Shibuya’s Ōyama-chō district in Tokyo, where Japan’s largest mosque, the Tokyo Camii, was built the same year. One presumes that Omar had some athletic background in boxing, as his first step towards what would become a career in combat sports, legit or not, was on juken shows, events which pitted judoka against boxers of foreign descent. This tradition went back decades (as early as 1909), but had been dormant for some time when it was revived after the war by future Japan Womens Pro Wrestling (1967-1972) president Morie Nakamura. Other participants in these shows included the son of the Tokyo Camii’s imam, who competed as Straight Roy and later became known as television personality Roy James, and Masahiko Kimura. The juken revival led to Toshio Yamaguchi's Osaka match against former rikishi Umeyuki Kiyomigawa on July 28, 1953, after which the two of them received support from local yakuza boss Shojiro Matsuyama for what became the All Japan Pro Wrestling Association. In February 1954, Omar worked the AJPWA’s first show as Killer Mike Yusuf. (A show program from that April claimed that he had a 20-2 boxing record, and had fought in the Mediterranean, Middle East, Egypt, and India.) By July, though, he had switched sides to the JWA. In a 2012 interview with G Spirits magazine, Yusuf said he had left the AJPWA because "he got fed up with what was being said about him", but did not elaborate. Rikidozan renamed him Yusuf Turk in reference to his heritage. His ring name is more accurately transliterated as “Yusuf Toruko”, or Yusuf Turkey, but I have decided to simply use Turk, as that is what Haruo Yamaguchi does in his Crowbar Press book on Rikidozan and the JWA. Hisashi Shinma, who worked out at the JWA’s Japan Pro Wrestling Center in the mid-fifties, claimed that Turk would train his neck by hanging dumbbells on his headgear. In 1956, Turk entered the light heavyweight bracket of the Unified Japan Championship Tournament, and defeated Hideo Higashi in the first round in 40:15. Ultimately, though, Turk is most remembered as a wrestler for early examples of comedic puroresu. Many years later, when Antonio Inoki sought to insult Giant Baba in a caustic Gong interview, he did so by invoking the “comic show wrestling” that Turk had practiced. While Rikidozan was in Hawaii in the summer of 1958, he wrote a letter to referee Kyushuzan in which he alleged that “a reckless undercard wrestler of Turkish descent” had threatened to make his Korean origins public. Despite these tensions, Turk continued to wrestle for the JWA while doubling as a referee. He also made strides into film and television acting. Turk in the 1959 Nikkatsu film University Rampage. Records indicate that Turk pivoted fully into refereeing after Rikidozan’s death, with only a few subsequent matches noted in the second half of 1964. When Oki Shikina was arrested for firearm possession in 1965, Turk got promoted to a head referee. He can be seen officiating the main event of the JWA’s first Budokan show in December 1966, the brutal and timeless clash between Giant Baba and Fritz von Erich. But his most famous incident from this period did not take place in the ring, but in a hotel lobby. In January 1968, the Great Togo returned to Japan for what would be a disastrous tenure as the IWE’s talent booker, and in doing so broke a promise he had made never to work in the country again when the JWA paid him off after Rikidozan died. Physical retaliation was chosen, but Turk (and undercard wrestler Gantetsu Matsuoka) took the initiative and ambushed Togo. According to one account, Turk asked Michiaki Yoshimura to punch him afterwards in order to make it look like Togo had fought back, but instead had to strike himself in the face before he turned himself in to the police. As Turk had hoped would happen, the police did not take him into custody, and only warned him that he should leave his fighting to the ring. As Togo’s reputation plummeted for losing a fight to a referee, Turk was put under indefinite suspension…as far as the public was concerned. In reality, JWA president Junzo Yoshinosato had sent Turk on vacation with a round-the-world ticket. Antonio Inoki wins the 11th World Big League on May 16, 1969, after a final match which Turk refereed and booked. In early 1969, as Togo sought to form his own Japanese promotion with Lou Thesz’s backing, Kokichi Endo maneuvered to negotiate a second television deal with NET TV. As the plans for what would become World Pro Wrestling were set into motion, the JWA needed to raise the stock of a top star to carry the program, as Giant Baba (and, at first, Seiji Sakaguchi) would be Nippon Television exclusives. Turk was among those who lobbied heavily for Antonio Inoki to win the 11th World Big League tournament that spring, and the tournament was booked to bring Inoki, Baba, Bobo Brazil, and Chris Markoff to a four-way tie at the end. Turk officiated the second tiebreaker match, where Inoki debuted the octopus stretch to defeat Chris Markoff. Three days later, Inoki sat at the press conference to announce World Pro Wrestling. In 2012, during a talk with joshi pioneer Sadako Inagari and historian Etsuji Koizumi, Turk indicated that he had booked that final match, and deemed it his masterpiece. Due to this, and the central role that referees played in booking matches in early puroresu, it is generally presumed that Turk had a major role in laying out Inoki's late-JWA singles matches, and it is known that he booked matches in early NJPW. Over the two years to come, this two-TV setup would divide the JWA into factions around Baba and Inoki, and Turk fell squarely into the latter camp. So much so that, after Inoki wrestled his final match for the company on December 7, 1971, Turk led him to take a different exit out of the building and saved him from a planned ambush in the locker room. Inoki checked himself into a hospital for protection at Turk’s suggestion, and when he got out, Turk was at the center of plans to form New Japan Pro-Wrestling. Mortgaging his home to raise capital, Turk was the company’s second largest shareholder upon its formation. In the ring, he was a referee and booker. It has long been reported that Turk ultimately left NJPW over a dispute with Hisashi Shinma. However, a 2019 G Spirits interview with Shinma and Naoki Otsuka claims that the issue was more complex. According to Shinma, Turk and Inoki had developed some friction over the booking of an October title defense against Red Pimpernel, and Turk had then taken offense that he had not been made involved in the ultimately aborted JWA merger. Otsuka claims that it had ultimately been NET TV that wanted Turk out for his suspected yakuza ties. Whatever the case, Turk announced his departure in February 1973. Turk accompanies Abdullah the Butcher in his shocking NJPW debut on May 8, 1981. It would be several years before he returned to pro wrestling. Turk sold real estate in Hawaii and ran an electrical company, but he would enter what Wikipedia calls “special shareholder activities” while using making connections in the political and business spheres. Turk had been friends with mangaka Ikki Kajiwara since the Rikidozan era, when Turk was among the JWA talent who appeared in a 26-episode television adaptation of Kajiwara’s licensed manga Champion Futoshi. It is known that the two at one point planned to start their own wrestling promotion, Dai Nippon Puroresu (Big Japan Pro Wrestling), with a Fuji TV deal, and with top sumo wrestlers Takamiyama and Chiyonofuji as aces. Former JWA official Shigeo Kado wrote in 1985 that these plans dated from autumn 1978, while Turk claimed in 2002 that they did not attempt them until 1983.1 Whatever the case, it was this connection that sowed seeds for Turk’s reconciliation with New Japan, even if it would also lead to another estrangement. On February 27, 1980, Turk refereed his first NJPW match in seven years: Inoki’s different styles fight against Kyokushin karateka Willie Williams, which had its roots in a tie-in with Kajiwara’s late-70s series Shikakui Jungle. Turk would then help facilitate the start of 1981’s infamous Pullout War, in which Hisashi Shinma sought to destroy his competition once and for all through swiping top AJPW talent. Turk got him in touch with its biggest heel. Abdullah the Butcher had asked for a raise but did not receive a response. Abdullah made a pitch through Turk to Shinma, and the rest is history. Long-forgotten plans would follow for a different styles fight between Inoki and a man Turk represented named Hashim Muhammad, who appeared at Inoki’s January 1982 match against the Butcher. Turk’s association with Kajiwara, in whose Kajiwara Productions company he held an executive position, would eventually put an end to this period with New Japan. In 1982, Kajiwara attempted to hold Inoki and Shinma hostage in a hotel room over what could have been a dispute over either unpaid Tiger Mask royalties, or Inoki having founded his own karate dojo. This was one of several Kajiwara incidents that came to light when he assaulted Monthly Shonen Magazine editor-in-chief Toshikazu Iijima the following year, all of which compounded to destroy the author’s reputation in his final years. Just one month after the Iijima incident, Kajiwara and Turk were arrested for attempting to extort the ghostwriter of an Abdullah the Butcher book from the previous year. Turk appears to have continued involvement with Kajiwara afterward, as he can be seen in footage of the July 31, 1984 AJPW show where Mitsuharu Misawa first appeared as Tiger Mask’s second incarnation. (Notice him in this screenshot as Jumbo Tsuruta makes his entrance.) On February 22, 1989, Turk was given a retirement ceremony at New Japan’s Special Fight in Kokugikan, at which Toyonobori made what may have been his final public appearance as a guest. The following year, when Inoki sought to make a political trip to Iraq before the Gulf War began, it was Turk who pulled strings to get him on a Turkish charter flight to a country no others would fly to. Before his 2013 death from heart issues, the elderly Turk had been seen refereeing for Satoru Sayama’s Real Japan Pro Wrestling, as well as pitching a truly bizarre freelance show in 2010. FOOTNOTES

-

Naoki Otsuka and the Early Years of NJPW

Interrupting things here. This is the best stopping point I will have until I finish 1975, and I want to ask you all a question. Would you mind if I put things on hold to rewrite earlier posts? I have become extremely dissatisfied with the early numbered posts, which basically assumed that readers would already know the in-ring part of NJPW's first year, and then hopped around back and forth to cover important matches. (To say nothing of how I crammed all the young lions into one post after realizing that I had not written about them at all and panicking as I was two-thirds through 1974.) I want to expand the first post into multiple ones that put Otsuka and Shinma's valuable insights into proper context, and then put Singh, Thesz/Gotch, Powers, and Kobayashi in proper order. Which brings me to my next point. Are you all cool if I post the expanded versions on my blog instead of here? I have been piggybacking on PWO's SEO for a while now, but I think it's time for something new. I want to write nothing less than the best serial ever written about puroresu in English, and I want to be able to showcase that on my own site.

-

Naoki Otsuka and the Early Years of NJPW

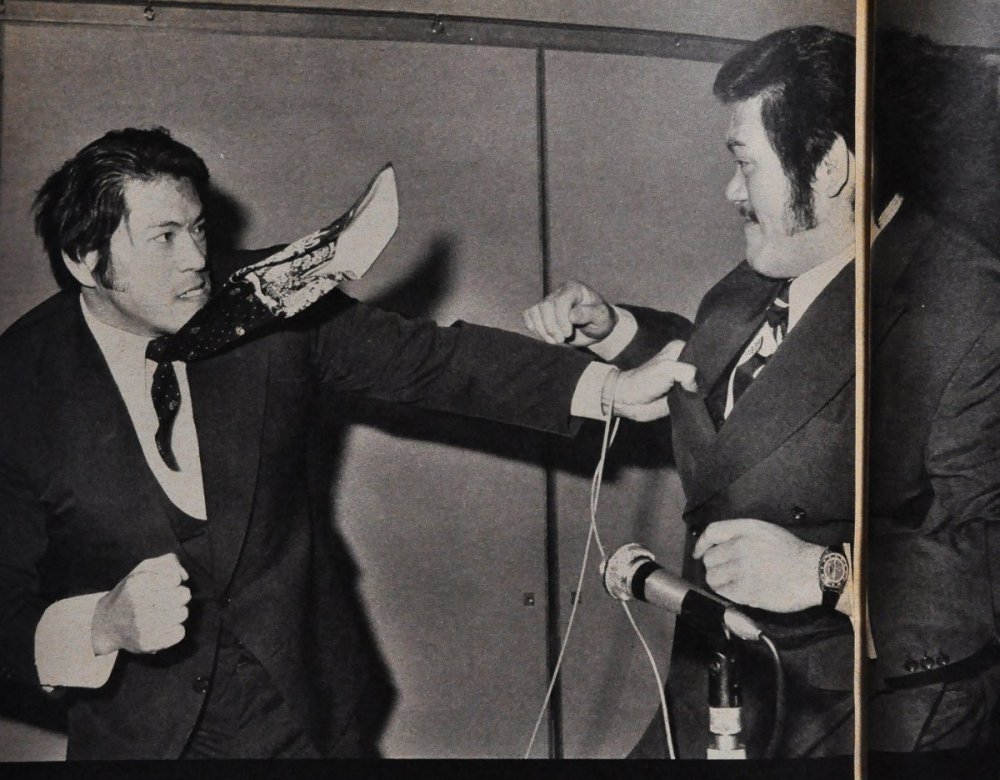

Sources used for this post include: NAOKI OTSUKA AND THE EARLY YEARS OF NJPW, #9: THE LION AND THE DRAGON The last full tour of the year was the nearly forty-date Toukon Series II. To my knowledge, the only match from this tour that circulates—besides the last, which we will get around to—is a b-show tag where Inoki teamed with Osamu Kido against George McCreary and Roberto Soto. This match was released on the twenty-disc 50th anniversary Inoki DVD set, which was later repackaged as a 60th anniversary set on four Blu-Ray discs. It’s a great shame, as this tour featured some very interesting matches. While the tour had a consistent slate of second-tier gaikokujin, there were three different top foreigners across its seven weeks, and two of those three would never work for New Japan again. (As mentioned previously in the thread, the first Karl Gotch Cup, predecessor to the Young Lion Cup, also took place during this tour. Tatsumi Fujinami won the final against Masashi Ozawa.) This photo of Ernie Ladd was used in the tour program and on the poster for the Sapporo show where he challenged Inoki. The first was Ernie Ladd. The Big Cat had wrestled fulltime for half a decade by this point after retiring from football. In spring 1970, he placed fifth in the IWE’s You Are the Promoter fan poll, which scouted interest in wrestlers who had not yet been booked in Japan. As they did with numerous names on that list, the JWA preempted their competitor, and Ladd was one of the first they booked. That autumn, for the first NWA Tag Team League tournament, Ladd teamed up with a wrestler he had only surpassed in the poll by nine votes, Rocky Johnson. That tour’s pamphlet hyped up Ladd as wrestling’s biggest “black power” since Bobo Brazil, which was true! But alas, Ladd would make far less of an impact in Japan. (The black wrestler who would truly succeed Brazil in that regard, Abdullah the Butcher, had debuted on the previous tour.) On March 21, 1974, he challenged Inoki for the NWF title in what was essentially the promotion’s final show in Cleveland. As reported by Gong in their October 1974 issue, Ladd had challenged Inoki in the locker room of the Olympic Auditorium after the tag title match. It was originally announced, in fact, that the October 10 Kuramae show would be headlined by Inoki vs. Ladd, until the Oki program was made official. Instead, Ladd got his shot at the champion in Sapporo on the first of November. It was the first time that Inoki defended the title in Hokkaido, which would not happen again for three years, and apparently, it was lackluster. Ladd’s minibio on the Showa Puroresu website reads that it was supposedly due to bad weather, while a commenter on Japanese Yahoo Answers alludes to an interview in 80s magazine Big Wrestler where Ladd claimed that he had been sick, but that Inoki had not known this and judged his performance as an unmotivated one. [Addition, 7/21/2024: Mr. Takahashi's 2001 shoot book Bloody Magic makes a claim that explains a lot: Ladd had completely forgotten the layout of the match.] Whatever the case, Inoki went over clean this time, and in postmatch comments he said this bode well for his singles match against Andre the Giant, which we will cover in due time. For Ladd’s part, his only work in Japan after this was a 1980 summer tour in AJPW, where he teamed up with Bruiser Brody to challenge for Baba and Jumbo’s NWA International tag titles. Inoki and the Sheik headlined two straight nights in Okinawa. This is from the first, November 12. Now, it is time to talk about the only six dates the Sheik ever worked for New Japan. NJPW had bought the rights to the NWF title and brand, but the room to run the promotion’s turf had gone to a far closer promoter. Ed Farhat had run Detroit’s Big Time Wrestling with his father-in-law since 1964. In the early decade, it had weathered competition from Dick the Bruiser and Wilbur Snyder’s All Star Championship Wrestling, but that was gone now. After a cancelled booking with the JWA in autumn 1971, he debuted in Japan the following year, when he challenged Sakaguchi for the vacant NWA International Heavyweight title in a pair of matches. In spring 1973, the Sheik had debuted for AJPW, challenging Baba for the PWF Heavyweight title in one of just four surviving matches from the pre-Jumbo era of the company. (Supposedly, he was booked to make up for Dory Funk Jr.'s cancellation after the shoulder injury that ended his NWA title reign.) As mentioned in #7, Farhat had voted in favor of NJPW’s membership at the 1974 NWA convention. Now, he was booked to wrestle for them for two weeks. He only wrestled one, for as soon as he had left the States, top BTW talent and staff led by booker Jack Cain left the promotion to run as International Wrestling. The dates that Farhat did work were bookended by matches against Sakaguchi: first a DQ, then a double countout. For New Japan’s second trip to Okinawa, he and Inoki fought on consecutive nights. In the first match, Inoki was goaded into disqualification, and on the following night’s lumberjack match, Farhat infamously pulled an Ernie Ladd (ha) and left the ring. He left on the 15th to sort his house back in order and did not return to Japan for three years. Andre the Giant joined the tour on its 21st show on November 19. He had worked the Big Fight Series back near the start of the year, where with the assistance of manager Frank Valois, he had dealt Inoki his first singles loss since Gotch in 1972. (Note: I incorrectly described this as a clean loss in a previous post, having not had proper information on the match. I have since corrected that.) On the final show of that tour, underneath Inoki vs. Kobayashi, he had wrestled Sakaguchi. Now, he worked the last fifteen shows of the tour, followed by NJPW’s first shows in Brazil, which we will address at the very end of the post. The December issue of Gong would have been on shelves by or around the time Andre set foot in Japan. Trust me: we need to talk about this. The magazine featured interviews with Baba and Inoki on the matter of a match. Baba admitted that the match was what fans wanted the most, and he himself thought it would be a great match that would go down in wrestling history. However, Baba said that that match would not happen because someone was challenged. He said that a unified promotion would have to be formed and that the match could be realized when they were integrated into one organization and covered by one TV station. These are things that, even in late 1974, the parties involved must have known would never, ever happen again. Showa Puroresu features a condensed version of Inoki’s caustic response. You may be familiar with the quote in which Inoki contrasted his strong style with Baba’s “showman’s style”. Well, he was long past that now. Inoki proclaimed bluntly that Baba and the Destroyer had deteriorated even further. Tiger Jeet Singh, the Sheik, Abdullah the Butcher, Andre the Giant, and the Destroyer of old were showmen: wrestlers who played to the crowd, yes, but who were competent, and who were wrestlers. “When something is called professional wrestling, the fight at least must be serious.” Inoki said that Baba-san was getting close to a “comic show” style of wrestling, of which he named the JWA undercard heels Mr. Chin and Yusuf Turk as examples. Furthermore, Inoki rejected the sentiment that the two and the styles they represented could coexist, calling it “Baba’s deception”. Baba was “the main reason why people said wrestling is what it is”. No matter how delicately Baba framed the matter, it did not dissipate the perception that he was “retreating” from a challenge that Inoki had made, even if Inoki had made the challenge without thinking through its feasibility. Now, Inoki was implying that Baba and his wrestling were an existential threat to wrestling itself. Unbeknownst to Inoki, though, Baba was about to make a major power play that would significantly restore his reputation. NWA Worlds Heavyweight champion Jack Brisco was preparing to leave the States for a set of AJPW dates when he received a call from Terry Funk. Baba wanted the belt for a week, and he was offering $10,000 for it. Brisco reminded Terry that he had paid the NWA a $25,000 bond. Ultimately, he set a bold range of terms. He would go through with the pitch if Sam Muchnick approved and if Baba paid back his bond in full. On top of that, he wanted an extra two grand for each day he was in the country and eight grand for each match with Baba. He would be in Japan for eleven days, and he would work three singles matches with Baba. For those keeping score, Brisco wanted Baba to pay over $70,000 (over $400,000 in 2023). Finally, he wanted the bond money as soon as he got off the plane, in American dollars. These were terms that Brisco did not expect to be fulfilled, and even Terry was surprised when Baba agreed. Brisco went through with the plan, but his honesty and Midwestern values compelled him to tell Muchnick, Eddie Graham, and Jim Barnett what they were going to do. When Brisco got off the plane on December 2, sure enough, the bond was right there in a briefcase. That night, as New Japan ran a provincial show in Ehime, Baba beat Brisco in Kagoshima in just under 21 minutes to become the first Japanese NWA heavyweight champion, with Pat O’Connor attending as witness. Four days later, as Inoki and Sakaguchi defended their tag titles against Andre and Roberto Soto in Osaka, Baba followed up with a successful defense against Brisco in Tokyo, where he also put his PWF Heavyweight belt on the line. Baba got his week exactly, as he dropped the title back on an untelevised show in Aichi. As Brisco learned at the tour’s end, you could not leave the country with more than five grand in cash, so he taped the stacks to his body for the long, nerve-wracking flight to Hawaii. When he landed back in the States, Brisco met in a car with Muchnick, who wanted a cut of what Baba had paid him. This moment likely contributed to the fatigue that led the NWA champion to infamously no-show the 1975 convention to force them to vote on a new champion. If so, this was a vote that Inoki held some indirect responsibility for. On December 6, Inoki and Strong Kobayashi met in a press conference to sign a contract for their anticipated rematch on December 12. Kobayashi had left for the States in spring. In between stints with the WWWF, where Hisashi Shinma had gotten him an MSG title shot against Bruno Sammartino, he had come down to work the Florida territory as the masked Korean Assassin, an associate of Gary Hart. This had led him to cross paths with Baba, who came in June to attempt to collect on the bounty that Hart had placed on Dusty Rhodes. Baba offered him a booking with All Japan, which it was not too late for Kobayashi to do, but he felt too much gratitude to Tokyo Sports for having gotten him out of Kokusai, and politely declined. In contrast to the cordial press conference before their first match, a now-mustached Kobayashi assaulted Inoki. (A 2022 Tokyo Sports article suggests that this now-standard angle had been very rare, if not nonexistent, in puroresu up to this point.) On the morning of the day, Inoki made a speech in the Noge dojo: "Do you know why I am going to fight Oki, Kobayashi, and Baba? I'm not fighting just to show off my strength. I'm fighting to show as many people as possible that wrestling, which is still seen as a show, is serious competition. Tonight, I will fight Strong Kobayashi again. Kobayashi will be even more desperate than last time, so I can't underestimate him this time. But I'm going to fight to the death, too. I have no intention of losing. That's because a New Japan Pro-Wrestling fight is always a fight to win.” Before the match in Kuramae, Inoki gathered his young lions in the locker room and reiterated his intentions: "They say that professional wrestling is a game of eight hundred tricks [a Japanese expression for a fixed sport], but I will prove with this match that it is not so. You should watch this match with an open mind. This is the kind of wrestling you have to do. We are going to restore the reputation of wrestling." Kiyomigawa, who by now had likely taken his coaching job with AJW, did not return to referee the rematch. This time, that duty fell to Corsica Jean. One half of the successful Corsicans team of the turn of the sixties, the French-Canadian was apparently recommended by Gotch. After Yusuf Turk’s acrimonious departure in 1973, New Japan did not hire a full-time foreign referee like the JWA and contemporaneous AJPW had (with Jerry Murdock in both cases). Rather, they would use the gimmick sparingly to add extra prestige to significant matches. Of course, it would be another year before Red Shoes Dugan stepped on the lion’s mat. Inoki caught Kobayashi off guard with his first offense, a pair of dropkicks and a bodyslam, and went for a pinfall which Jean counted without noticing Kobayashi’s rope break. As the crowd roared, show organizer and Tokyo Sports business head Takahashi (I only have the surname, and the guy definitely doesn’t look like later editor-in-chief Noriyoshi Takahashi) entered the ring and insisted that the match be restarted, backed by who I presume were other employees. The match was indeed restarted, and Kobayashi lasted almost half an hour before Jean called the match by referee stoppage. After this, New Japan left for Brazil. This was Inoki’s first visit in three years. At the end of 1970, he had traveled there with a NET TV crew to shoot a nature documentary, which was derailed when Inoki was bitten in the ankle by a jararaca snake. (Kosuke Takeuchi had covered his bases in case Inoki died by giving the next cover of Gong, which featured him, an unusual black background.) Brazilian immigration records indicate that Inoki had gotten his mother Fumiko back home in 1973, when NJPW received network support. I don’t know nearly as much as I would like to about this tour, as Otsuka doesn’t have anything to say about it. I am certain, though, that Keisuke Inoki must have played a major role. Gotch would tag along on the tour, wrestling his beloved pupil Osamu Kido and Masashi Ozawa. They crossed paths with Ivan Gomes. The son of a cowboy, Gomes had trained in boxing and judo/jiu-jitsu alongside his brothers, José and Jaildo, before beginning a career in vale tudo in the late 1950s. He first became known for his appearances on Heróis do Ringue, a television program hosted by the Gracie family. After this program was canceled due to an incident where João Alberto Barreto broke the arm of his luta livre-practicing opponent, Gomes moved to the show Bolsa ao Vencedor. He had a difficult relationship with the Gracies—website BJJ Heroes put it succinctly, calling him “the man the Gracies didn’t want to fight”—which ultimately ended with an offer to open a dojo with Carlson under the condition that Ivan never challenged them again. He took the offer, but his relationship with the first family of BJJ dissolved, and he handed it off to Jaildo in 1968 to return to professional fighting. By 1974, he had opened another school in his hometown of Campina Grande. First, Gomes came to Inoki to challenge him. However, he was intrigued by the training that he saw when he came to visit, and instead offered to join New Japan. Gomes would be NJPW’s first proper “exchange student”, working for them across the next two years until an infamous match on their second Brazilian tour. But the hire looked forward to the shift towards martial arts that Inoki would make in the second half of the decade, as well as the future signing of Olympian judoka Allen Coage. Inoki also met Hiroo Onoda, the Japanese holdout who had surrendered in the Philippines that same year (and, of course, the eventual inspiration for Akira Maeda’s entrance theme). On December 20, Inoki was awarded the Order of the Southern Cross from the Brazilian government. There was a photo of the ceremony in the following tour’s program, although I couldn’t find a better list than the one on Wikipedia already, which doesn’t have him. Inoki was the first athlete to receive the medal. As for the shows, NJPW held two. In Sao Paulo on December 15, Inoki wrestled his first singles match against Andre since March, and the earliest among them that survives today. It ended in a double countout when Andre walked over to the ropes while Inoki had his arm in a keylock but was tumbled over to the outside. Four days later in Londrina, Andre challenged for the tag titles again, this time with Tony Charles. Yet again, he was not enough to make up for the shortcomings of his partner. Inoki meets with famous Japanese holdout Hiroo Onoda and Ivan Gomes.

-

Motoyuki Kitazawa