Everything posted by KinchStalker

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

I don't know as much on the subject as I would like; as I have stated elsewhere on the board, my Otsuka/NJPW thread is on hold because I am trying to get a bit more context for South Korean pro wrestling. But the industry was propped up hard by the Park regime. The president of the promotion itself, which was known as the Kim Il Supporter's Association until 1982, was Chung-hee's bodyguard, "Pistol" Park Jong-gyu. Chung-hee apparently paid for the Kim Il (later Cultural) Gymnasium, a commission which Oki hooked his architect buddy Lee Chun-sung up with. I can't verify this, but I remember reading somewhere that the promotion had lost television coverage at some point, but that Chung-hee forced it to go back on TV. In the 2019 Kim Duk interview that gave me a lot of info for the Oki/Korea post, he also notes that Jong-gyu’s wife was a huge fan and basically a patron. Oki always went out with a cadre of KCIA bodyguards. Et cetera. Everything seems to point to a simple explanation for the decline: the promotion had been coasting on government funding. I raised an eyebrow when reading Showa Puroresu state that tickets for the March 1975 Kim Il/NJPW tour ranged from 4 to 15 won, a tenth of Japanese ticket prices (that top amount equated to about ¥900 at the time). Kim Duk has this to say about his life as a trainee in 1967: “All the money for food and stuff came from the Korean Wrestling Association. In other words, money from the government. I stayed at Mr. Oki's house for about three months, but the other trainees complained, so I moved into a training camp. We young guys were paid as well. We were paid about ¥3,000 a month. All living expenses were covered by the association, so we could eat out and live on that salary. Prices were cheap.” I should also note that South Korea clearly didn’t have the infrastructure for the kind of tours that Japanese promotions did. You never read about them working in provincial markets. I only ever read about shows taking place in about half a dozen cities, the smallest of which was Pyeongtaek, which had a population of around 200,000 in 1975. Oh, and that gym? It was in the Changdeokgung Palace garden.

-

[1991-01-26-AJPW-New Year Giant Series] Mitsuharu Misawa vs Akira Taue

I've never talked about this here, but I have elsewhere online. I am convinced that the way Taue took the Tiger Driver '91, which would become the standard for the move, was not the original intention. On April 5, Misawa used the move again on a Carnival match against Kobashi in Takamatsu. As seen in a camcorder recording, Kobashi lands on his shoulder blades. Excerpt from 2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 10-17, PART FIVE: I believe that the Tiger Driver '91 was originally conceived as a followup to the standard Tiger Driver, where Misawa drove his opponent down rather than flip them into a sitout pin. Nothing more, nothing less. This era of All Japan is marked by sequences of similar but distinct maneuvers that trade on the aesthetic benefits of repetition. Think of Misawa's multiple-suplex finishes in the early big Kawada matches. It is used in the Kobashi match in the same way, as a followup to a Tiger Driver nearfall. Misawa might be a dick here, but him going "fuck your neck, Taue" on a trial series match is out of character and out of step with the broader product. This is not 6/3/94. Perhaps the height difference between Misawa and Tsuruta/Taue led him to decide to put the move on ice. I suspect it was shelved to put over the stepover facelock as Misawa's new finish instead. But by 1994, when the nightmare bump arms race was on, I believe the move was retconned to have always been intended the way that Taue took it. (Weekly Pro coverage of the Kobashi match [special issue #432 (May 5, 1991)] did not contain a photograph of the finish, which likely obscured the contrary evidence.) I cannot confirm any of this, but it feels much more plausible to me than the notion that this superfinisher was busted out three years before it came back again. Baba, Fuchi et al. were good, damn good, but they were booking a wrestling promotion, not writing Babylon 5.

-

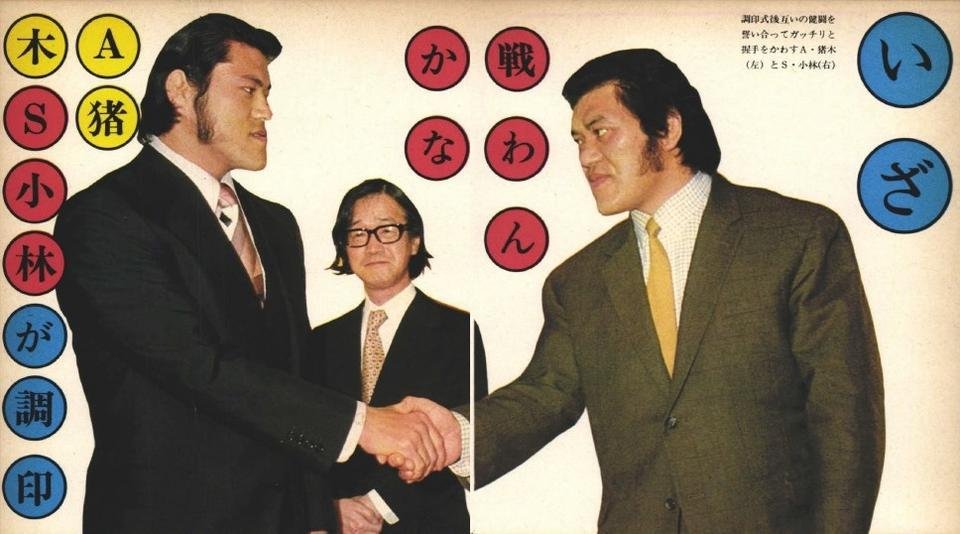

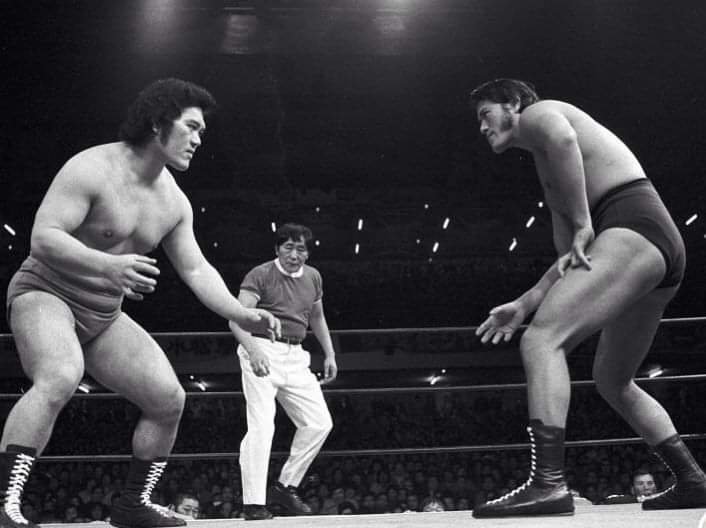

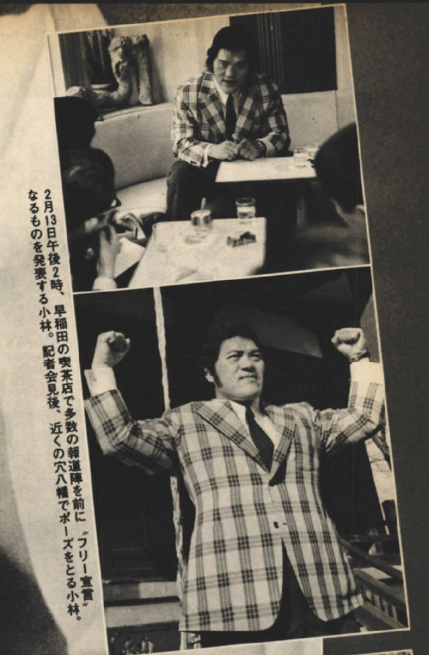

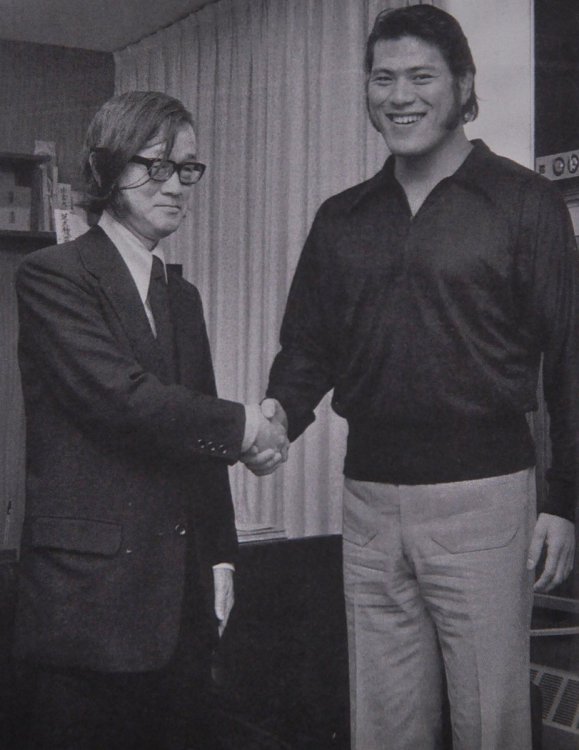

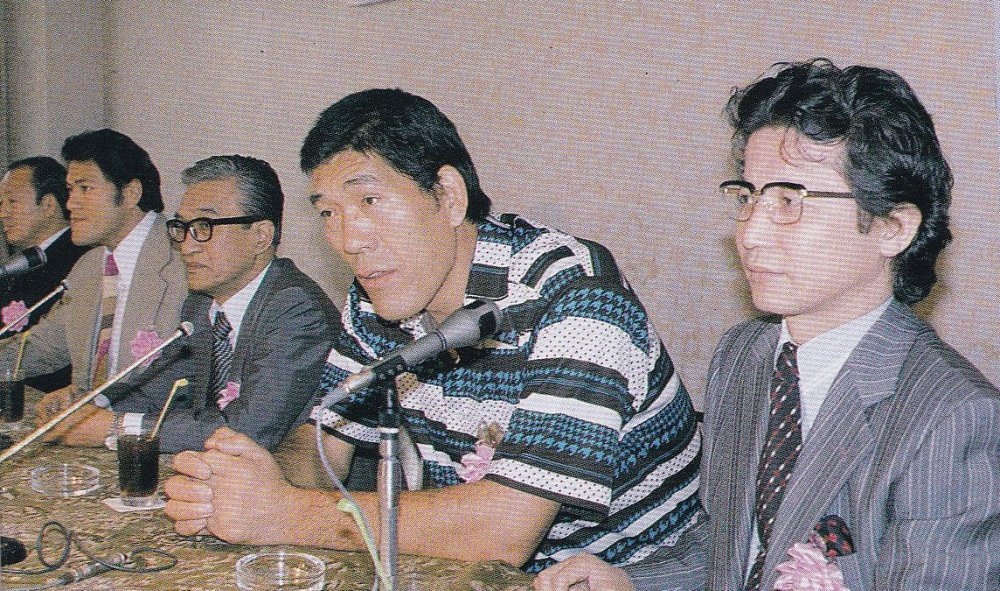

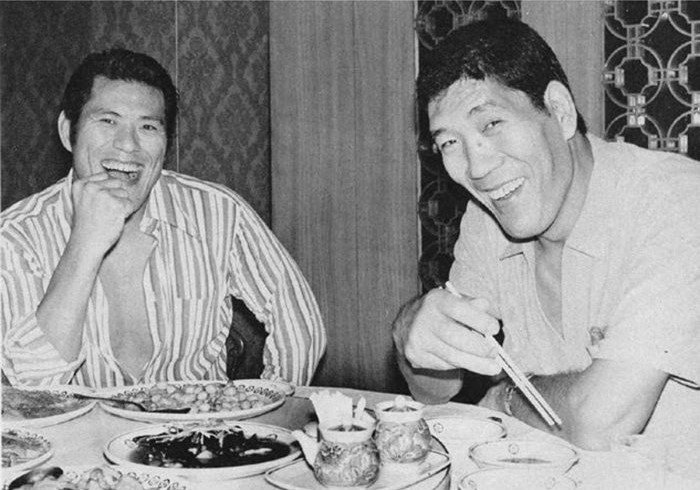

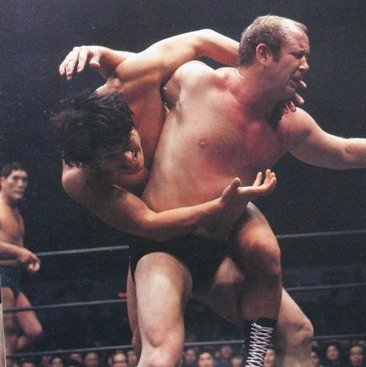

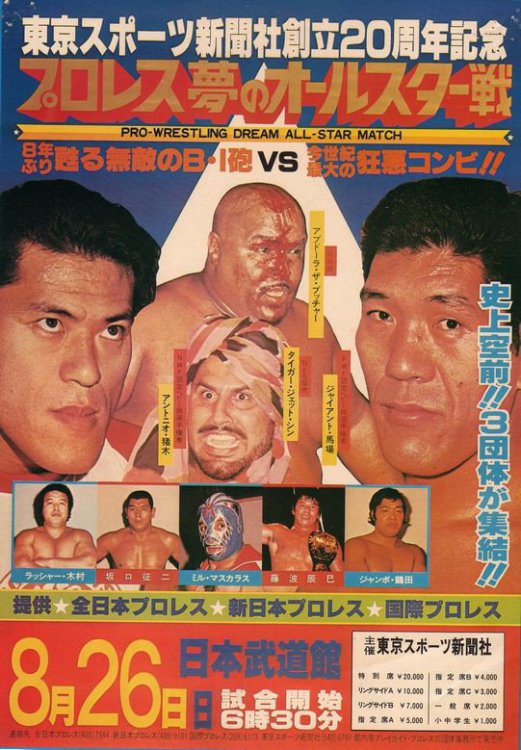

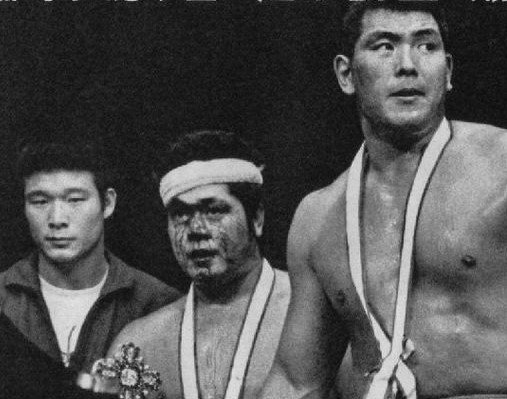

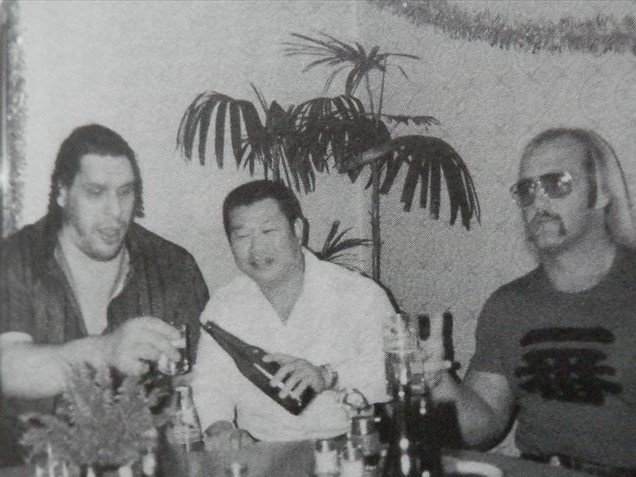

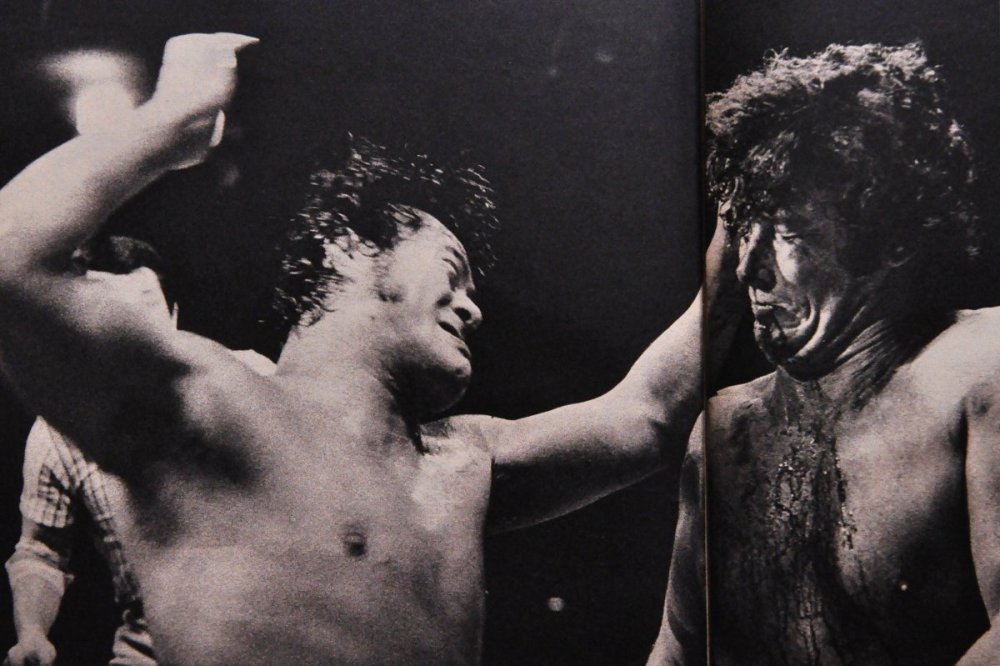

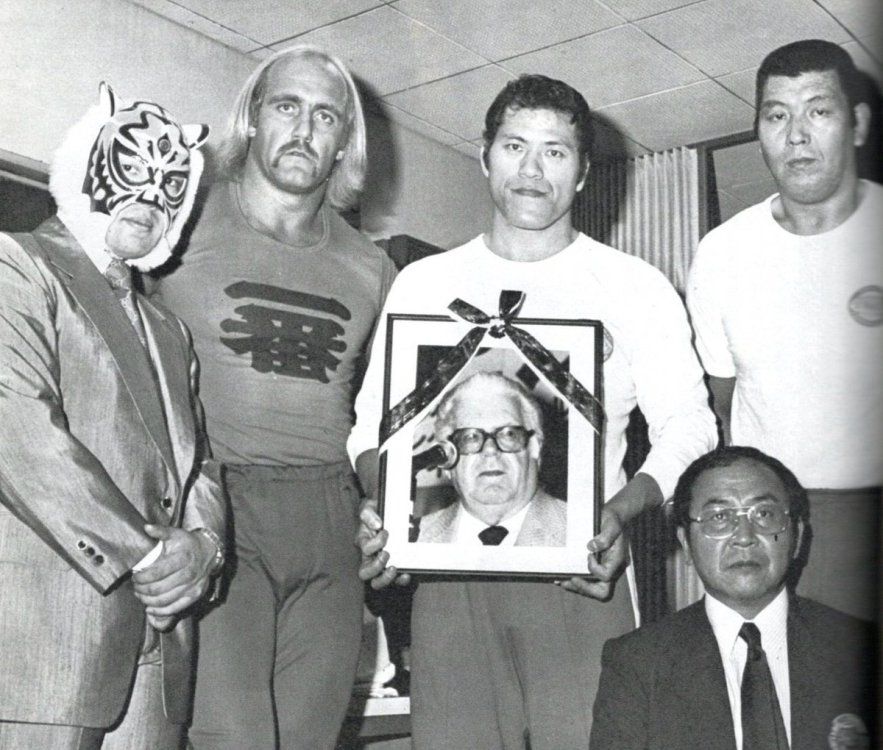

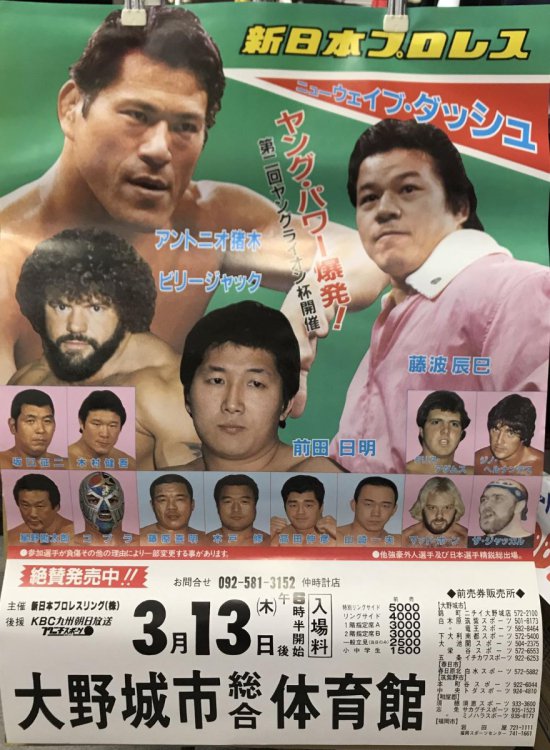

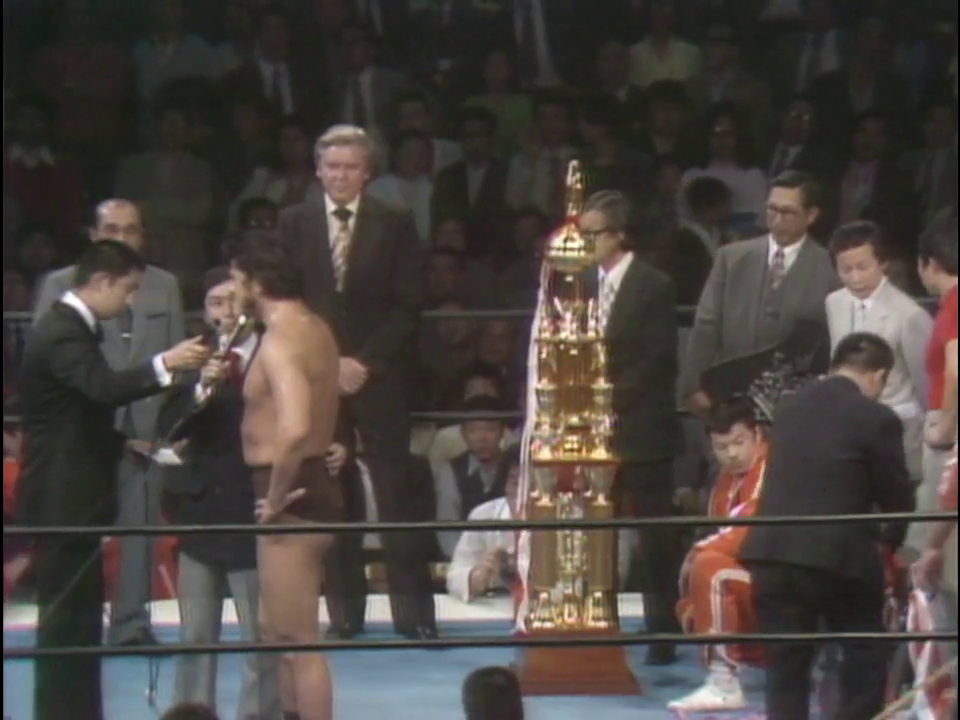

Pro Wrestling Dream All-Star Match: The 1979 Tokyo Sports Show

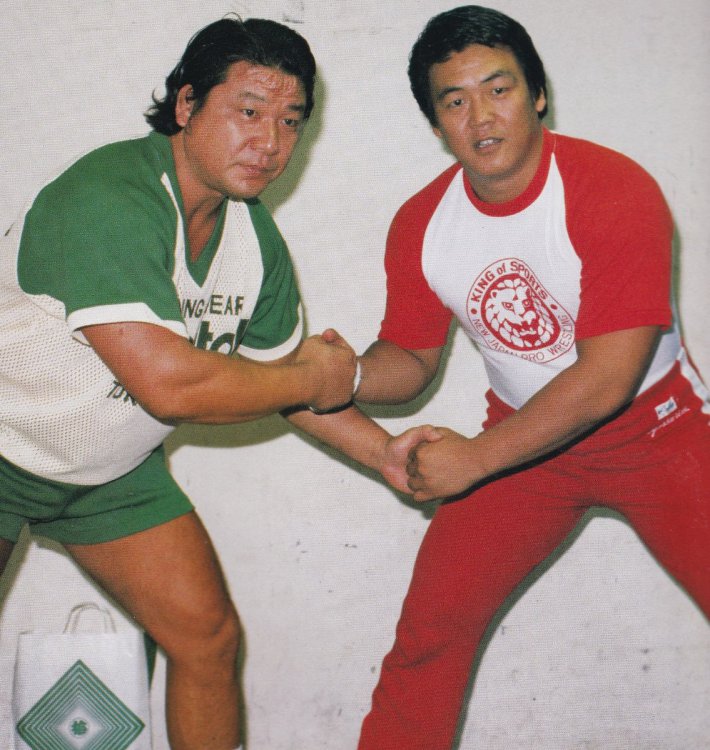

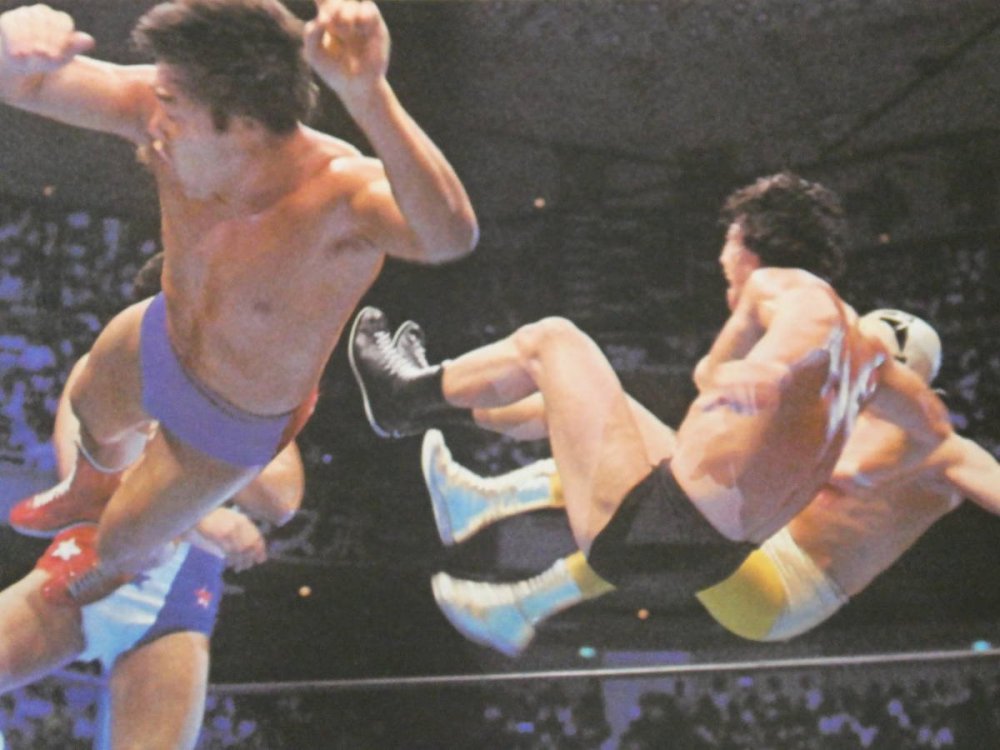

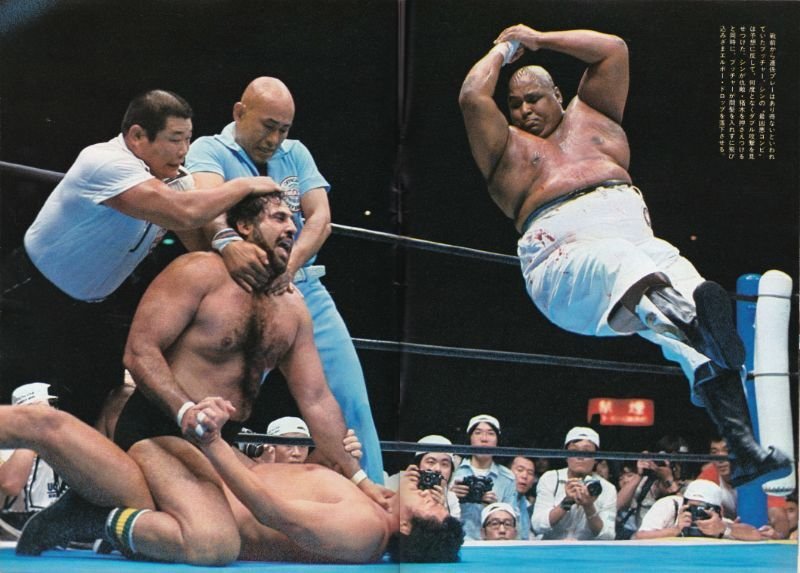

This was a topic that I had not planned to write about for a while: not until I reached 1979 in the NJPW/Otsuka thread, by which time I would have properly contextualized it with all the years of politicking between All Japan and New Japan. But your friend and mine, Loss, will soon reach this point in his Wrestling Playlists Newsletter, and I cannot leave our brother in the lurch (or try to have him cram all the interesting details in there himself). This, as best as I know it, is the story of the 1979 Tokyo Sports show. On March 8, 1979, Giant Baba and Antonio Inoki met for a private Chinese dinner in Roppongi with Tokyo Sports editor-in-chief Noriyoshi Takahashi and sports department head (and World Pro Wrestling color commentator) Yasuo Sakurai. The most powerful paper in puroresu had big plans for the year, but they needed these two on board. Both men had been consulted in February, after groundwork had been laid in a meeting between top executives of all three puroresu organizations: NJPW’s Hisashi Shinma, AJPW’s Ryozo Yonezawa, and the IWE’s Toshio Suzuki. Now, Takahashi and Sakurai needed to see if they could stand to be around each other. The story goes that they left for forty minutes to see if Baba and Inoki, who had not dined together in over seven years, could get along. When they returned, the two were reminiscing happily. It would not go this smoothly for long. On May 22, Tokyo Sports representative director1 Ryotaro Motoyama used its front page to urge Japan’s three pro wrestling organizations to clash in a joint show for their 20th anniversary. Coverage of this commemorative event would give the paper the excuse to raise its price by 10 yen, which would help them make back the investment of putting on the show; since 1974, they had increased their price twice due to their role in promoting major NJPW matches (namely, the first Inoki/Strong Kobayashi match, and the Muhammad Ali fight). Most of the proceeds would be split between the three promotions. New Japan held a press conference immediately and approved. The following week, though, Baba's reluctance was made clear in comments printed by the paper. He noted that Inoki had said "terrible things" about him, that Inoki had proclaimed he would not do business with All Japan because Baba had dodged his challenge; now, they waited on Baba's call. Baba acknowledged that Inoki and New Japan's provocations may have stemmed from passion, but at worst, they had obstructed his business. When the Tospo interviewer asked if Baba wanted them to retract their previous comments, Baba denied it, but he wanted them to "be reasonable". The March dinner had been arranged with the understanding that Inoki could not walk back his years of public comments without compromising his image, and the account of that meal shows that there was still a common bond between them, but Baba still leveraged that past beef in public comments. Yoshiwara, Inoki, Motoyama, Baba, and Takahashi at the June 14 press conference. A press conference was scheduled for 11:30, but bad weather delayed Baba’s flight, and he did not land in Tokyo until 12:20. The conference finally began at 12:44, with both Baba and Inoki in a sour mood. It had been announced that the full details of the show would be revealed during the conference, but all that ended up confirmed was that the Budokan was booked for August 26. When a reporter asked Takahashi what card they had in mind, the editor admitted that he wanted to book Baba vs. Inoki. In fact, Tospo wanted to realize other top dream matches, such as Abdullah the Butcher vs. Tiger Jeet Singh and Jumbo Tsuruta vs. Tatsumi Fujinami. The tension on this point showed through in the conference, with Inoki remarking that if they were going to do a joint show, he didn’t want it to be “a festival”. But Baba played the same refrain that he had for years, and also invoked the need for a unified Japanese commission that represented all parties’ interests. Earlier that year, New Japan and Kokusai had created one between themselves, but had only asked All Japan to accept it after the fact. Speaking of Kokusai, Isao Yoshiwara noted that their joint shows with All Japan had been difficult to coordinate, and that a full three-way show would be even more difficult. Nevertheless, he was willing to do business. After the conference, the parties continued talks in a private meeting. Baba left for AJPW’s show that evening, and the Destroyer’s subsequent farewell party, but returned late that night. During these talks, Inoki was reluctant to accept the alternate pitch of a one-night-only BI-gun reunion, as he wanted assurance that this would lay the groundwork for a future Baba vs. Inoki match. As Baba was set to leave for the States, and Inoki for Pakistan, both men gave full power of attorney to others to start the booking process: Inoki to Japanese commission head Susumu Nikaido, and Baba to Tokyo Sports itself. Nikaido and Motoyama met at the House of Representatives’ 1st Assembly Building on July 4. The Funks defeated BI-gun in their final match on December 7, 1971. BI-gun’s opponents would be decided in a fan poll with a July 14 deadline. Issue #16 of the Showa Puroresu zine records the top thirty results, but the top three teams left the other suggestions in the dust: Tsuruta & Fujinami, with 34,405 votes; the Funks, with 40,876; and Abdullah the Butcher & Tiger Jeet Singh, with 41,193. Over seven years earlier, the Funks had been the team’s final opponents. Inoki had objections to another Funks match, seeing where their loyalties lied as bookers for AJPW. Perhaps speculation is irresponsible of me, but one doubts that a Funks win would have been printed if the parties involved had no intention of fulfilling it. There has been at least one confirmed case of this phenomenon, which occurred in similar circumstances. In 1995, Baba would force Weekly Pro Wrestling reporter (and AJPW creative consultant) Hidetoshi Ichinose to falsify the results of a similar poll for All Japan’s six-man tag match at the Bridge of Dreams show, whose top choice had been Mitsuharu Misawa, Kenta Kobashi, & Giant Baba vs. Toshiaki Kawada, Akira Taue, & Jumbo Tsuruta. The August issue of Monthly Pro Wrestling featured a list of predicted matches, which was likely written at a point when the Funks topped the poll. I doubt that any of the other matches had been provisionally booked when the article would have been written, but they are nevertheless worth reprinting in the footnotes.2 On July 25, a second meeting was held to discuss matches that were not the main event. The second press conference afterwards announced the whole upper card, with Baba and Inoki far friendlier towards each other. The poster was unveiled, and tickets went on sale. Ringside “A” seats went for one million yen each, with “special seats” double that (roughly $23,500 today). From there, the rest of the first floor seats ran from ¥5000 to ¥7000, and the second floor seats ran from ¥2000 to ¥4000, with a 50% discount in general seating for kids in junior high and below. On August 1, the full card was announced, and four days later, Yoshiwara stated that Joe Higuchi, Mr. Takahashi, and Mitsuo Endo would all serve as referees, alternating as primary official while the others assisted. All advance tickets were sold out by the day of the show, and the general seats all sold out on the day. Some fans had even camped out at the venue the previous night. Among those in attendance were Keiichi Yamada, the future Jushin Thunder Liger, and future NJPW announcer Hidekazu “Kero” Tanaka. 7,000 pamphlets were printed, and all sold out despite their ¥500 price; a mail-order pamphlet would also be produced. (For perspective, a Budokan show at this point in time generally only needed to print two to three thousand units, and those were priced at ¥200. The mail-order system was presumably unprecedented.) The show began at 6:20. All Japan’s ring had been unavailable due to their ongoing Black Power Series tour, so New Japan provided theirs. After speeches by (Noriyoshi) Takahashi and Yoshiwara, and an entrance ceremony, the night began with a battle royal for a ¥300000 check. 15 participants had been announced, but the final match had four more. Seven wrestlers represented All Japan and New Japan each, with Kokusai rounding things out with five. At the end of the twelve-minute match, NJPW booker Kotetsu Yamamoto made the first graduate of the AJPW dojo, Atsushi Onita, submit to a Canadian backbreaker. He said he would share the prize with him at the time, though it is unconfirmed whether he did. According to G Spirits Vol. 20, this battle royal had developed from the original idea of an Onita singles match against the young Akira Maeda. While mostly filled with rookies, Sakurai suggested that Yamamoto be added as a "neutralizing agent". Baba allegedly suggested that Bobo Brazil, who was then working a tour with All Japan, could join the fray, but this did not materialize. The first proper match saw NJPW’s Makoto Arakawa face the IWE’s Snake Amami. Nicknamed the Kagoshima Championship for their shared origins (though this moniker is confusingly shared with Arakawa’s matches against Masanobu Kurisu), the match was reportedly an effective one. Arakawa won with a hip drop. Sadly, Amami’s career would barely last into the new decade, and a brain tumor took his life one month before his 30th birthday. In the first of two matches where one half of the IWA Tag Team champions teamed with an NJPW star, Mighty Inoue joined forces with Kantaro Hoshino to face Osamu Kido & Takashi Ishikawa. At the start of the year, Inoue had worked a program with the Yamaha Brothers to win back his company's tag belts, and his being booked (by Kotetsu Yamamoto) to lose a fall by submission would influence his resolve never to work for New Japan when Kokusai crumbled in 1981. But on this night, apparently, he and Hoshino made a good team. Less so Kido and Ishikawa, as the latter's relative inexperience and sumo background contrasted with the rest of the participants. At one point, though, Ishikawa blew Inoue out of the ring with a sumo tackle. Half a decade later, those two would team up for two lengthy All Asia reigns. Next was the first of two six-man tags on the card. Ashura Hara, the last great hope of the IWE, would be working with two wrestlers on their return match from expeditions. Kengo Kimura had worked in Puerto Rico, Mexico, and Los Angeles (billed as Pak Choo in the latter two territories), and at this juncture there were hopes that his return to New Japan could replicate the Dragon Boom that Tatsumi Fujinami had triggered in the spring of 1978. (Kimura claimed many years later that, before this match, Hisashi Shinma had strongly encouraged him to receive a facelift to increase his marketability to female fans.) Akio Sato, who Kimura had debuted against in 1972, had been Baba's valet when he started All Japan, but had left for the States in 1976. There, he had mainly plied his trade in the Midwest while learning how to book from George Scott and finding love with fellow wrestler Betty Niccoli. Their opponents were Haruka Eigen, Yoshiaki Fujiwara, and Isamu Teranishi. According to Showa Puroresu's show recap, Sato gave a disappointing performance, perhaps not helped with being paired with the likewise dry Eigen. I will allude multiple times to a roundtable discussion on the show that was published in Gong, which featured all three active Tokyo Sports reporter-commentators (Sakurai, Takashi Yamada, Takashi Kikuchi) as well as puroresu journalism pioneer Hiroshi Tazuhama. Someone on that panel went so far as to say that Sato had regressed since leaving for his excursion. Kimura would be pushed as a major junior talent in the year to come, which would culminate in a run with the NWA International Junior Heavyweight title. Sato would not make a proper full-time return to Japan for two years, but would become an important figure in AJPW’s reinvention in the new decade, working behind the scenes as a booker and on-site supervisor. The match had a safe ending as Hara pinned fellow Kokusai talent Teranishi. The fifth match of the night is the last one that, to my knowledge, does not exist on tape. (Showa Puroresu writer Dr. Mick—who I am certain did not attend this show, as I know he’s from Osaka and he would have been just a child—implies in his show coverage that he has seen video footage of the previous match, which suggests that there is either more footage from the same taper that I will address soon, or an alternate recording.) It’s a shame, too, because it features the one interpromotional dream team that actually had a future. Animal Hamaguchi had spent two years as an IWE tag champion, built up by a reign alongside Great Kusatsu before teaming up with Mighty Inoue to form one of the most definitive (and certainly the most chronicled) IWE teams. But tonight, he shared the corner with Riki Choshu, two months after Choshu had won the NWA North American tag titles alongside Seiji Sakaguchi in Los Angeles. On the other corner, Motoshi Okuma & Great Kojika represented All Japan. They had Choshu in their control in the first half, but the debuting team got something going against Kojika. While he was helpless in Hamaguchi’s airplane spin, Okuma intervened and then assaulted Mr. Takahashi to lose by foul play. Match #6 was the second singles match of the night, and the first match on the audience recording in circulation. On one end was Seiji Sakaguchi, probably New Japan’s #3 star. On the other was prominent AJPW midcarder Rocky Hata. It may not surprise you to learn that this match was not the original plan. Although it had been announced at the August 1 press conference, it is known that Sakaguchi’s original opponent was IWE booker Great Kusatsu. Kusatsu shot it down, as Showa Puroresu reported in 2008 and as then-valet Masahiko Takasugi confirmed in a late-2010s G Spirits interview. I happen to have the issue with the Takasugi interview, but I had not scanned it before my scanner broke, and I do not have access to my transcription method. So I cannot give any more details from Takasugi. But Showa Puroresu notes that Kusatsu was frequently mistaken for Sakaguchi, and that his refusal may have been a petty one along these lines. I feel that not wanting to work a match that one had not booked themselves could be a plausible explanation, but everything I know about Kusatsu suggests that the SP account is possible. Kusatsu attended the show. Hata was reportedly nervous, and had spent the whole night before drinking. He lasted six and a half minutes before a jumping knee and atomic drop ended his misery. In the Gong roundtable, Kosuke Takeuchi asked Sakurai outright if they really could not have found Sakaguchi a better opponent. Sakurai said that Jumbo Tsuruta, Rusher Kimura, Kusatsu, Tiger Toguchi, and others had been considered, and credited Inoki with suggesting Hata. The second six-man followed. Jumbo Tsuruta, Tatsumi Fujinami, and Mil Mascaras joined forces in a boy fan’s dream against a trio of lone wolves: Masa Saito, Akihisa Takachiho, and Tiger Toguchi. The babyfaces would be dubbed the Bird Men Trio, and all three got to show their unique styles. This match had developed from the original Fujinami vs. Tsuruta pitch, which Baba had rejected. After Baba had also rejected a Fujinami-Tsuruta tag match, Sakurai suggested that Mascaras be added, and Baba finally approved. One must commend Saito and Takachiho in particular, who had recently worked alongside each other in Florida. The future Great Kabuki had joined AJPW on its then-ongoing Black Power Series tour, making his first appearances in Japan since early 1978. He had left out of disillusionment over Samson Kutsuwada’s attempted mutiny, and it has been speculated by Dr. Mick that both Takachiho and Kazuo Sakurada had been eyed by Hiro Matsuda to effectively jump ship to New Japan the previous year, in what became the late-year Okami Gundan angle. (Mick cites a tip in a 1978 issue of Gong where a Mr. S and Mr. T claim that they want to work for NJPW.) While this show could never have happened with a conventional broadcast deal, production masters were created for the top three matches. These were for news programs, which would be allowed to clip up to three minutes for their reports. A production master of this match was created with the AJPW broadcast team of Takao Kuramochi & Takashi Yamada. This leads one to presume the agreement was that Nippon TV-affiliated networks could only air clips from this match, due to their contracts with the network. While the full tape has been lost to history—NTV once stated that they still had the edited version they aired on the news, though I have never seen it—we can see it on the fancam, and it holds up the best of the matches available to us. It's certainly better than what followed. As Sakurai admitted decades later, Isao Yoshiwara was reluctant to have his ace, Rusher Kimura, wrestle Kokusai deserter Strong Kobayashi in a grudge match. At the time, though, Sakurai credited Yoshiwara with pursuing the match in the Gong roundtable. Even the Kokusai devotee Dr. Mick doesn’t mince words; this one was a dog. Mitsuo Endo was the main referee, which bred concern about his loyalties. The crowd was about seventy percent in favor of Kobayashi, who lost by ringout. No matter how much Kimura protested on the microphone that he would challenge his former tag partner “anytime”, it was not a good look for the tragic ace, who was only eighteen months removed from one of the most humiliating losses in the history of puroresu against Baba. Yoshiwara had been willing to compromise his top stars for years due to his dependence on interpromotional matches for the cash flow from better-paying networks, such as Rusher’s early draws against Jumbo Tsuruta and Mighty Inoue’s clean loss to Tsuruta in the previous year’s Japan League tournament. If he was hesitant now, it was too late, and his company’s image cannot have been helped by this result. Kobayashi had relinquished his spot as Sakaguchi’s tag partner to Choshu, and the last major matches of his full-time career were in association with Kokusai. Plans were made for him to team up with the Rusher-led Kokusai Gundan heel faction in 1982, but Kobayashi’s pivot into entertainment made them moot. A production master was created by Tokyo 12 Channel, presumably with the Kokusai Pro Wrestling Hour commentary team of Shigeo Sugiura & Takashi Kikuchi, but it is now lost. Finally, BI-gun reunited one last time. Abdullah the Butcher and Tiger Jeet Singh had been the definitive foreign heels of their respective stomping grounds. Abdullah had debuted for the JWA in 1970. It was when he and Baba wrestled in the 1971 World Big League final that Inoki held the infamous impromptu press conference where he first challenged Baba. Since then, he had become AJPW's most popular heel, and this was the year where he worked five of the promotion's ten tours. Singh, meanwhile, was NJPW's first genuinely homegrown heel, a committed character wrestler who garnered massive early heat and had stayed relevant since. A production master was created with the World Pro Wrestling commentary team of Ichiro Furutachi & Yasuo Sakurai, with Sakurai's future successor on color commentary, Kotetsu Yamamoto himself, sitting in. A dupe of this tape eventually got into fans’ hands. (It had been available on YouTube but was taken down by NJPW. Only the abridged news report version is on there at the time of posting. But I trust you can find it yourselves.) After thirteen minutes, Inoki got a Joe Higuchi three-count on Singh with a bridging German suplex. After the match, Inoki grabbed the microphone. "Thank you all very much for coming today. Earlier, [PWF] Chairman Lord Blears gave me a very kind word to make the Baba-Inoki fight a reality. I am willing to risk life and death to make this fight happen. I will continue to work hard so that I can fight Baba. The next time the two of us meet in this ring, it will be time to fight!" Baba had no choice but to play along, exclaiming “let’s do it!” in response. This carried over into the subsequent press conference, where Baba acknowledged that there were still issues, but claimed that “he didn’t care about them now”. In truth, though, Baba had taken this as a sign that Inoki still could not be trusted. A 2022 column on the NJPW-AJPW rivalry by Kagehiro Osano reports that Baba had come to this conclusion due to a private telephone conversation the two had had a few days before. While this may or may not be the same incident, a recent article by Gantz Horie sees Shinma claim that the night before the event, Inoki had suggested to Baba that the match’s finish be changed to have them go over one of the two heels clean.3 The next day, Tokyo Sports hit the shelves with its new ¥50 price. FOOTNOTES

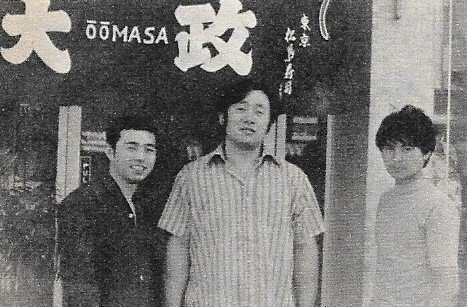

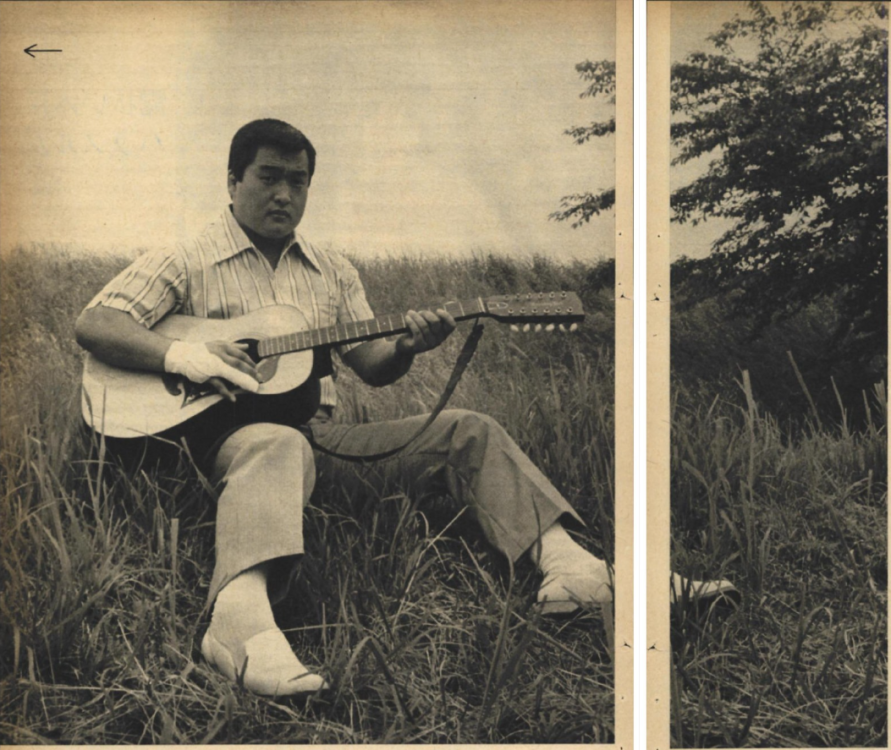

- Jumbo Tsuruta's musical career

-

Puroresu History on Indefinite Hold [NEW UPDATE]

Bad news. Funds for a new laptop are much more limited than I expected. There are some posts that I plan to write in the interim, such as one about the Tokyo Sports show which Loss will soon reach in his newsletter. But as before, I cannot process much of the resources I have acquired, due to my inability to type Japanese. As earlier stated, I refuse to continue the NJPW thread until I can transcribe a Pak Song serial that should give me context on the South Korean promoters that Oki competed with, and who Inoki later worked with.

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

Early puroresu music's love of cheesy slick jazz fusion made that stuff grow on me. NJPW had three guys come out to disco-era Maynard Ferguson at some point, one of whom was Hogan. AJPW's producers loved stuff orchestrated by Richard Hewson because he did the strings on "Sky High" (you are not ready for Dick Murdoch's theme from that period). There has to be an alternate timeline where Herb Alpert's "Rise" doesn't become a #1 hit off of General Hospital and thereby becomes cheap enough for one of the networks to license.

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

RIP to Johnny Powers, who reportedly passed away on the 30th. Here is a Greg Oliver obit.

-

AEW TV 1/4 and 1/6 - The One Where Danielson Wrestles Nese

On transit to BOTB now. It's my first wrestling show since a 2006 Smackdown taping, so as far as I'm concerned, I have the right to cut a little loose.

-

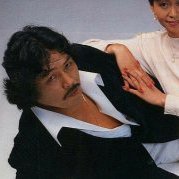

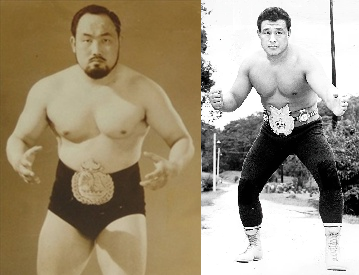

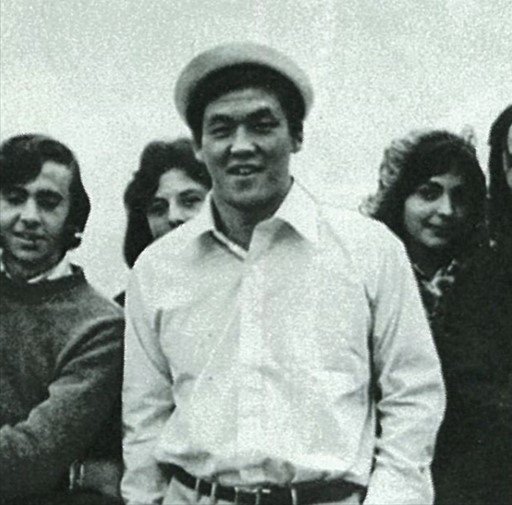

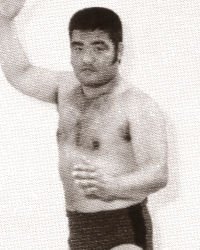

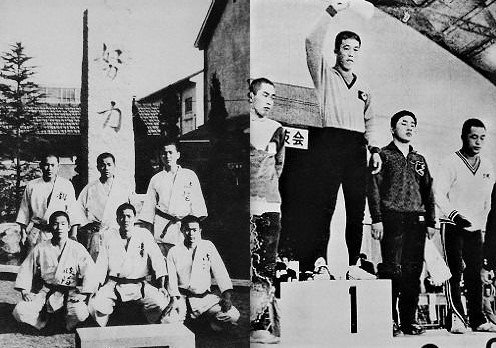

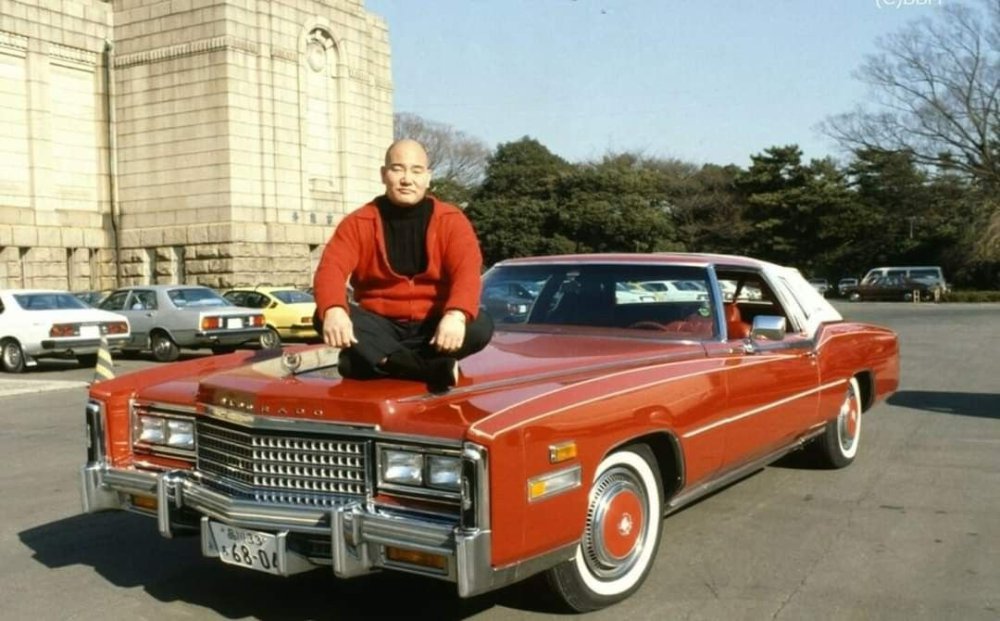

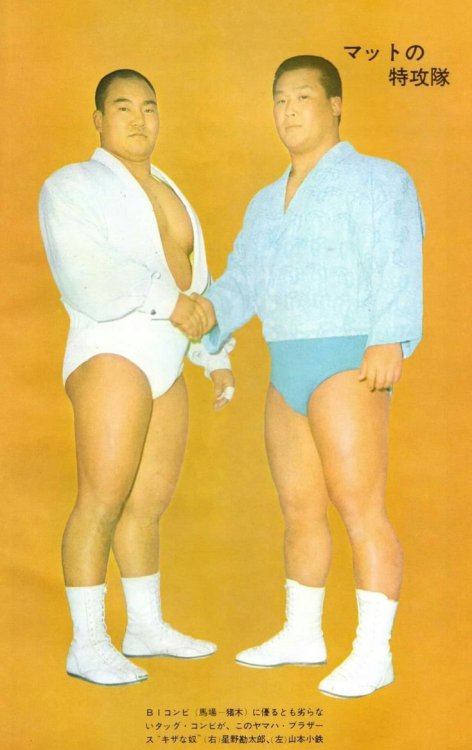

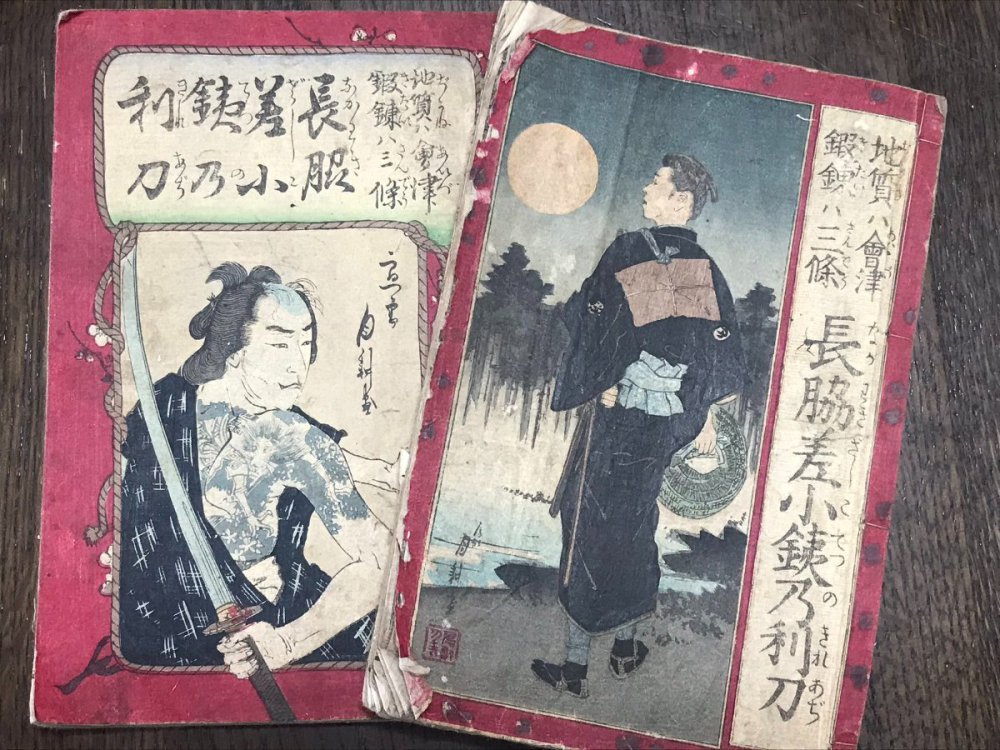

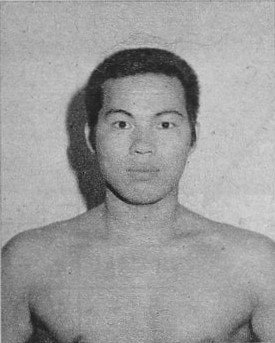

Kintaro Oki and the Birth of Korean Wrestling

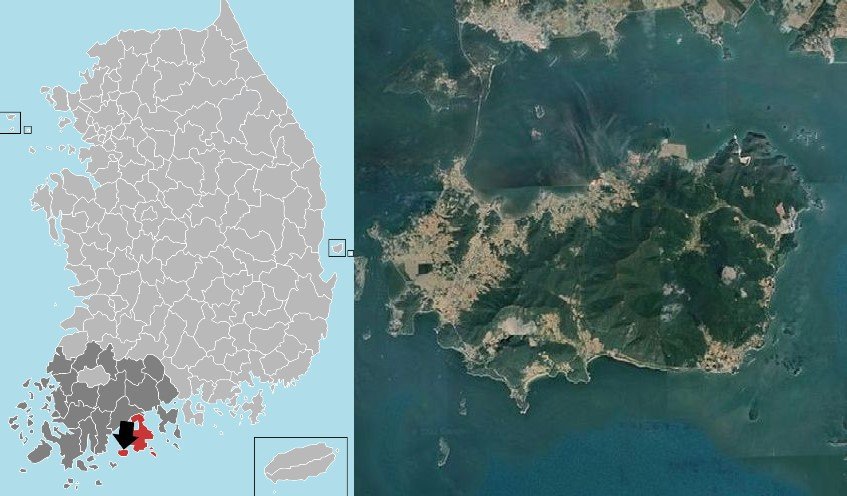

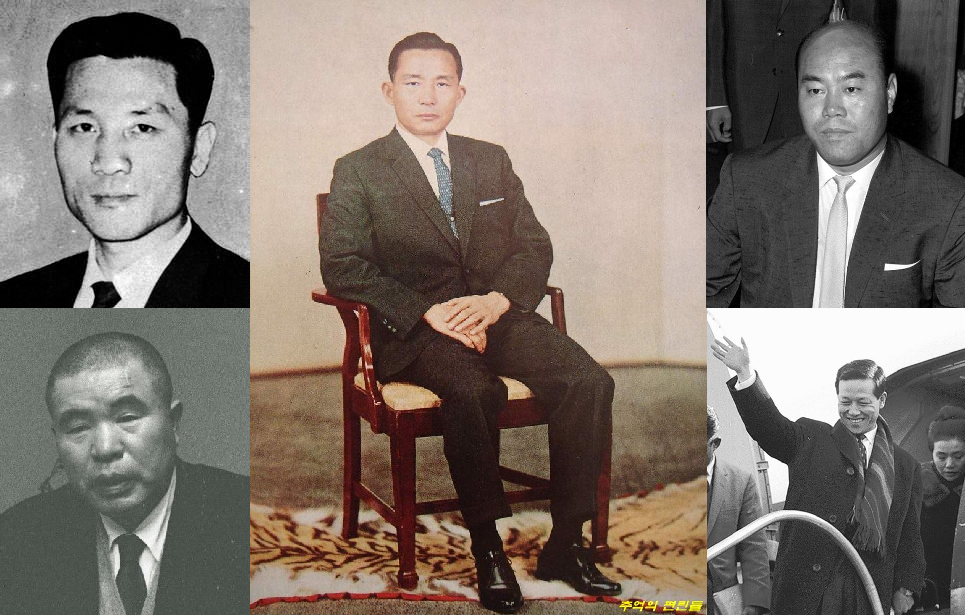

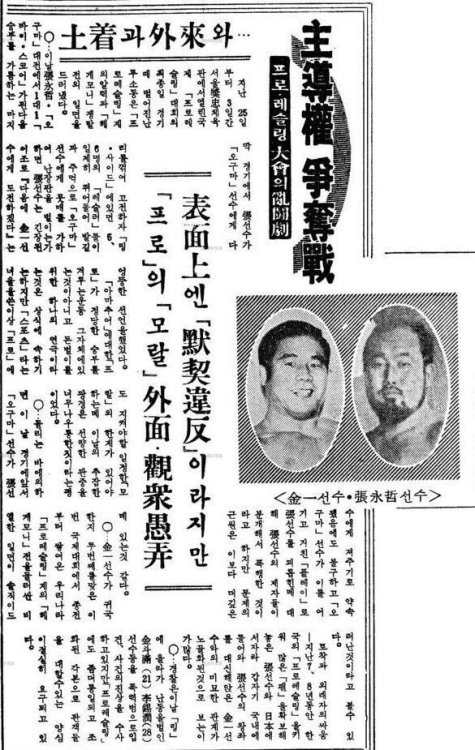

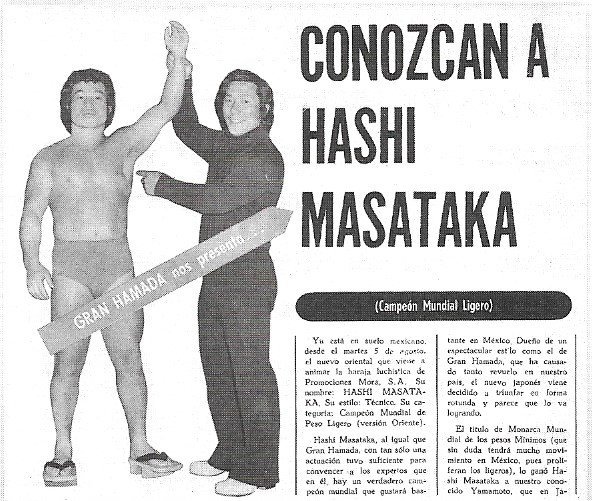

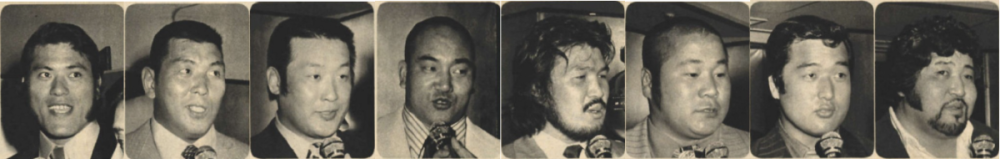

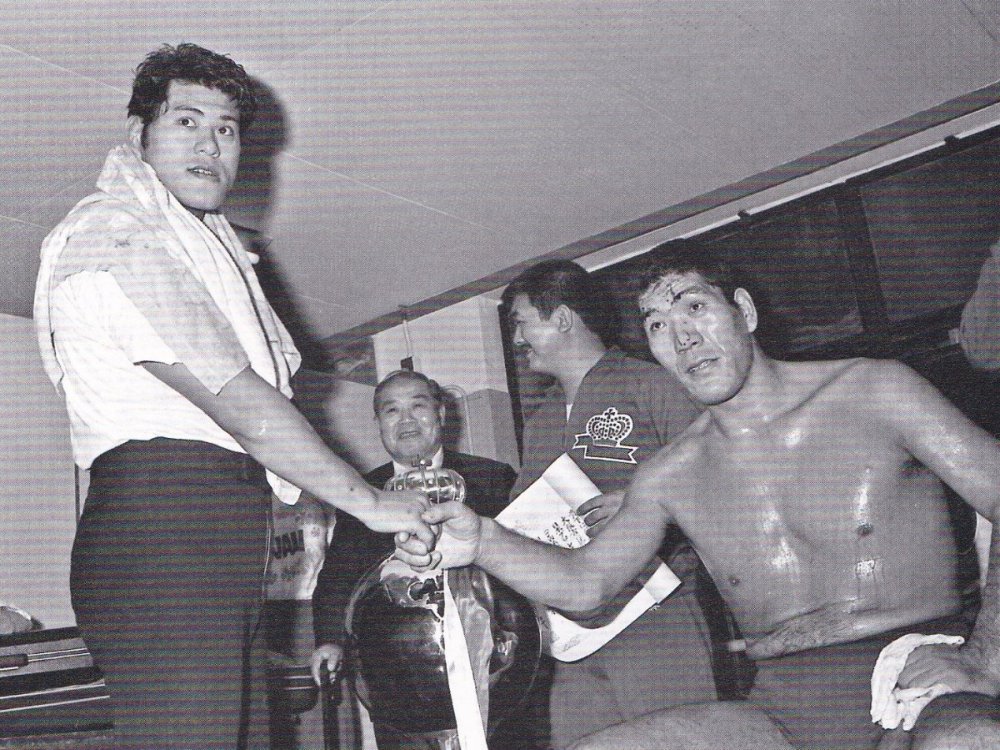

Gogeum sits about a mile south of the tip of the Goheung Peninsula. Its 63 square miles, bolstered by reclaimed land in the northwest, make it just a little bigger than Chicago. Kim Tae-sik was born in Gogeum in 1929, as his country sat beneath the “black umbrella” of Japanese annexation. Little of the island itself is arable, so Kim’s father farmed green laver. Although this practice has declined significantly in recent decades, it is likely that he did so using the traditional ‘racks’ method. Every year, he would have planted bamboo in the seabed. Then, he would have affixed nets to the sticks to catch floating laver seed. These nets would then be arranged in racks on the farm, submerged in high tide but exposed to the sun on low tide, and the seaweed bred from winter through spring. It’s a demanding process with low yield, and it should be little surprise that the Kims lived in poverty. Kim (center) with a calf won in ssireum. (September 1956) Tae-sik was the eldest of five. His future valet, Masanori Toguchi (Kim Duk), recalled the names of all but the third. Kwon-sik was the second, Yu-shik was the fourth, and Kwang-sik was the fifth, born in 1952.[1] As a child, Tae-sik had wanted to join a sumo stable in Japan. He would later compete in local ssireum tournaments where the prize was a calf. The legend goes that he won 27 of these, but Toguchi thinks this is an exaggeration. Tae-sik married Park Geum-rei when he was 16, and the two would have two sons and two daughters.[2] While Kim would have been able to watch wrestling on Japanese televisions in the Busan area, this isn’t what tipped him off to the existence of Rikidozan. Japan and the Republic of Korea had no diplomatic relations, but their fishery industries still did business together. It was a sailor at the Yeosu port who showed Kim a wrestling magazine. He made the hard decision to leave his family and smuggle to Japan on a fishing boat. The voyage from Yeosu to Shimonoseki, the city at the southwestern tip of Honshu, took 20 hours. Kim made it to Osaka and took a train to Tokyo, where he was arrested. Kim did time in a special prison for stowaways in the Kyushu city of Omura. He wrote a letter to JWA commissioner and Liberal Democratic Party politician Banboku Ōno, appealing to join the promotion. After nine months in jail, he was essentially released into Rikidozan’s custody in April 1958. The truth of these circumstances was not revealed for some time, as a 1961 Pro Wrestling & Boxing article claimed that Kim was a failed businessman who came to Rikidozan’s home and asked to join the JWA. It was not until the 1972 Gong serial “Tiger of Asia”, written by JWA Commission secretary general Shigeo Kado, that the real story was publicized. (This was one example of how Kado's writings, while likely sensationalized, were the most revealing of early puroresu journalism.) He was given the ring name Kintaro Oki. Kintaro, or “Golden Boy”, is a folk hero: a boy with superhuman strength.[3] Billed as being four years younger than he really was, Oki debuted in November 1959 as the second of puroresu’s first “four pillars” (after Yukio Suzuki). The following year, he was the debut opponent of one Kanji Inoki. Oki took well to Inoki backstage, believing at first that he was really Brazilian and bonding with another outsider. As Inoki disclosed in his autobiography, he lost his virginity on Oki’s dime in a Kumamoto brothel. Inoki wrestled him numerous times throughout the first four years of his career, eventually taking him to many draws but never beating him. [Note: I will be referring to Kim as Oki henceforth, for ease of reading.] In September 1963, Oki left for an American excursion; the story has long gone that it was originally intended for Inoki, but that a knee injury caused him to be passed over. Billed as a Japanese native, Oki teamed up with Mr. Moto in the WWA and won their tag titles from Bearcat Wright & Red Bastien on December 10. During this stint in Los Angeles, he created what would eventually become his Korean stage name. One night at a Korean diner, Oki met UCLA student architect Lee Chun-sung and introduced himself as Kim Il. Lee would connect him with the local Korean community, who attended his matches at the Olympic Auditorium. A decade later, Lee would design the Cultural Gymnasium in Seoul, which was initially owned by Oki's promotion. Oki at Haneda Airport in January 1964. After Rikidozan’s death, Oki returned to Japan on January 24, 1964. He had done so without permission, but was nevertheless allowed to work for them starting in February. He competed in the 6th World Big League, losing against Gene Kiniski and Caripus Hurricane to notch three wins, two losses, and one draw. On a Sapporo show on May 28, he debuted a ring name that he would work under intermittently for the rest of the decade, Kintaro Kongo (金剛金太郎). It was said at the time that he wanted to avoid confusion with head referee Oki Shikina, but this name had apparently been thought of by Rikidozan. According to Toguchi, Kongo was a reference to North Korea’s Mount Kumgang (금강산/金剛山). Top figures in the political and criminal spheres are involved in this story. Top to bottom, left to right: Park Jong-gyu, Yoshio Kodama, Park Chung-hee, Hisayuki Machii, and Kim Jong-pil. Oki returned to Korea for the first time in six years on June 27. According to his autobiography, he had come into contact with an agent of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency, who asked if he wanted to meet President Park Chung-hee. Smuggling to Seoul for ten days, Oki did not meet Park. He did, however, meet KCIA director Kim Jong-pil. Three years earlier, Kim had engineered the coup in which Park had seized power. He was an associate of Hisayuki Machii, the Yakuza godfather who ran the Tosei-kai and held the rights to promote JWA shows in the Tokyo market. Kim asked Oki to become “the Rikidozan of Korea”, and that would be taken rather more literally than one might imagine. Machii and Yoshio Kodama—ultra-nationalist, power broker, and president of the JWA’s shareholders organization—pressured the JWA in a summer meeting to allow Oki to adopt Rikidozan’s stage name in Korea. While the recently deceased Bamboku Ono had opposed the effort for Japan to sign a treaty with the Republic of Korea, these two strongly favored and facilitated it, as they stood to gain a cut of the investments that reparations money would go towards. Alongside the casinos and cabarets they would open in Seoul, it is clear that they planned to replicate the Rikidozan formula with Oki. In fact, they were carrying out what Toguchi suspects Rikidozan had intended all along. Rikidozan had visited South Korea at Kodama’s insistence in January 1963, and the Korean side had wanted him to hold and wrestle in an international tournament there. Rikidozan would never have agreed to this due to the risk that it would expose his secret in Japan.[4] As top wrestler-executive Junzo Yoshinosato later recalled, the only way that they got out of the demand was by setting an impossible condition. They would allow Oki to adopt the name…if he defeated the NWA World Heavyweight champion. After a brief return to Japan in August, reverting to his first ring name, Oki returned to the States in September and, well, he tried. On October 16 in Houston, he got a match with the NWA champ, a 48-year-old Lou Thesz. He went off-script with a shoot headbutt and was beaten and bloodied for it, to the tune of 24 facial stitches. While I do not know whether Thesz was ever made aware of the political context of Oki’s actions (I’m sure Koji Miyamoto could have told him the story at some point), the two would become friends. Thirty years later, Thesz pushed Oki’s wheelchair for his retirement ceremony, which took place during Weekly Pro Wrestling’s Bridge of Dreams show at the Tokyo Dome. Oki returned to Japan in June 1965. On June 11, though, the JWA expelled him for the match with Thesz, as he had gotten it booked through former JWA talent booker Great Togo. Togo was persona non grata in the JWA since he had extorted them for solatium after Rikidozan's death, which they only granted with his promise never to work in Japan again. Just two weeks later, Japan and the Republic of Korea signed the Treaty on Basic Relations. That same day, Oki met with Toyonobori in Tokyo. There is a factor that I have not discussed yet. Oki would be encroaching on another promoter's territory. Jang Yeong-chol and Chun Kyu-deok, the pioneers of Korean pro wrestling. Pro wrestling had existed in South Korea for four years. Jang Yeong-chol, a wrestling coach, and Chun Kyu-deok, a serviceman who taught taekwondo at night, had seen Rikidozan on Busan television. They had no one to properly teach them, so they had to learn secondhand.[5] They apparently ran first in Busan before taking their operation up to Seoul, in which they held their first show in June 1961. (Two months earlier, a trio of former JWA wrestlers—Osamu Abe, Takao Kaneko, and Mitsuo Surugaumi—had run a pair of Seoul shows.) They eventually earned the support of President Park Chung-hee, who expected them to run once a month at the 10,000-seat Jangchung Gymnasium once it was opened in 1963. Jang's promotion was built on matches against Japanese talent unaffiliated with the JWA. He did business with a group led by former AJPW Association wrestler Hisaharu Kaji, which as mentioned in Interlude #3.1 of my Naoki Otsuka/NJPW series included Mr. Takahashi.[6] In December 1964, they received network backing when Tongyang Television launched, thanks to future Seoul Olympics production director Kim Jae-gil. Jang would surely be interested in a JWA partnership, and Oki could not let that happen. Ultimately, Oki was successful. He wasn't brought back into the JWA, but he intended to wrestle in Korea anyway. Jang and Chun would be forced to work on his terms. On June 30, he landed in Seoul Airport to a hero's welcome. In the two months before Oki's Korean debut, Jang struggled with tensions in his ranks, particularly as to his top prospect. Pak Song-nam, a 6'6" giant he had scouted two years before, refused to swear loyalty to him. In early August, Jang allegedly had Pak abducted and held without food or water in a secluded mountain cottage near the Korean Demilitarized Zone. He was found after five days by a military patrol. Late that month, Oki wrestled as Kim Il for the first time in the Far Eastern Heavyweight Championship Tournament. He brought four JWA wrestlers with him: Yoshinosato, the former light heavyweight champion soon to become JWA president; Michiaki Yoshimura, the best worker of puroresu's first generation; undercard stalwart and onetime coach Hideyuki Nagasawa; and Umanosuke Ueda, a bone-dry technician yet to discover his voice as a heel. The Korean end of the tournament was Kim, Jang, Chun, and Pak. Oki defeated Yoshinosato to win the tournament and the eponymous title. An article states that "pro wrestling is a show". Three months later, the World Big League-inspired Five Nations Championship Tournament was held. The same four Koreans in the previous tournament competed against representatives of Japan, Turkey, Sweden, and Denmark. Yusuf Turk, who helped book the tournament alongside Oki and Shigeo Kado, represented Turkey. Karl Karlsson, seen donning a leather helmet in newsreel footage, represented Sweden. Denmark’s Viking Hansen was the future Erik the Red. Finally, three-year veteran Motoshi Okuma stood in for the JWA. On November 25, Jang and Okuma wrestled in a tournament match that went south when Okuma cranked back on a single-leg crab and Jang’s posse stormed the ring to break it up and beat him. The particulars of what happened next appear to have been misunderstood in decades of Japanese accounts. Their narrative went that Jang exposed the business to the police to keep his boys from being arrested. Chun asserted in a late-life interview that it had happened somewhat differently. Jang had kept his mouth shut, but the police had taken his silence as a confirmation. Regardless, the next day’s papers read that “pro wrestling was a show”. Jang lost his support from Park Chung-hee, and the dojo built for him in Seoul’s Samgakji area was taken over by Oki’s group. Jang’s faction also switched sides. In December, Oki defended the Far Eastern Heavyweight title against Ripper Collins. This was the first time that South Korea booked an American talent independently of the JWA, and with the financial backing of a dictator, it would not be the last. President Park's right-hand man, Park Jong-gyu, became the president of the promotion, named the Kim Il Supporters' Association upon its formation in 1967. FOOTNOTES

-

Puroresu History on Indefinite Hold [NEW UPDATE]

Just wanted to give an update. It looks like I will be able to get a new laptop soon, but I am waiting for the funds to come through. I have a computer available to me, but I do not have the authority to install Java on it, which Kanjitomo runs on. (I tried a mobile app called Kaku, but I just could not get a good workflow going with it. Even more than Kanjitomo, it was clearly designed for manga and visual novels, not dense text.) I have written over 2000 words of what originally was supposed to be the next entry in the NJPW/Otsuka series, which would at least cover the Kintaro Oki match. But 2000 words of that have wound up being solely about Oki's early career and the birth of Korean wrestling. I am preparing a thread solely devoted to that, so that I can get this information out there without bloating the Nooj series. What I have written goes up to the end of 1965.

-

Mammoth Suzuki

Major Update: This profile has been expanded with information from a 2019 G Spirits article by Etsuji Koizumi. This was the last Japanese resource that I was working on when my laptop went under, and I had transcribed about 85% of it. I plan to complete it when I have a computer to use Kanjitomo with again.

-

Rikidozan

Agreed. As a side note, the first-gen puro guy with the best reputation as a worker is Michiaki Yoshimura. He's solid in what I've seen, but we just don't have that much. The story goes that he was so good as a FIP that his daughter got bullied at school for how weak he was.

-

Puroresu History on Indefinite Hold [NEW UPDATE]

Bad news, brothers. The laptop is, indeed, FUBAR. I don't know when I will be able to get a new one. Any transcription is off the table for a while.

-

Puroresu History on Indefinite Hold [NEW UPDATE]

I brought my laptop to a local repair place, and while the diagnostic hasn't happened, I believe I have enough saved up to fix the issue. I backed up all of my files related to puroresu research, but again, transcription isn't feasible on mobile. Automatic OCR for Japanese is still so poor, particularly for a language so context -dependent, that it will take you more time to correct the errors and insert skipped characters than just to plow through it yourself with Kanjitomo, one to four characters at a time. And I can't do that. The last thing I was working on was the next entry in the Otsuka/NJPW thread, which will at least cover the Inoki/Oki match and the surrounding context. (Inoki vs Kobayashi II will either end this post or start the following one.) I wish to start it with a detailed Oki bio; and I have 1200 words written on his life through 1965. One of the last resources I transcribed before my laptop crapped out was an interview with Kim Duk, which provided excellent information. But I want a better sense of Oki's place in the Korean wrestling industry when he came to NJPW. He was its biggest star, yes, but I read that he was considered "anti-mainstream". I need to know what other promoters were working in the market before I am comfortable putting out the Oki bio, because those promoters would end up working with Inoki. I have a two-part G Spirits bio of Pak Song that I want to transcribe. Even though his match with Inoki doesn't happen for another two years, this article is the likeliest among my available resources to contain the necessary details. (There is another G Spirits interview on the JWA with the late former Tokyo Sports reporter and AJPW planning department head Teiji Kojima. I am quite interested in it, and while I am aware that that might sound like a waste of time for those interested in the NJ thread...I have to keep myself interested in this, okay?)

-

Puroresu History on Indefinite Hold [NEW UPDATE]

My laptop may have just gone FUBAR. For the last ten days or so it's been not detecting the replacement battery I got a couple months back. I know it's still in there because the battery charge was showing up, but the computer doesn't draw power from it. This has resulted in restart loops where some fluctuation in power supply or something messes a thing up and I have to go into boot menu stuff. Now, the keyboard lights flicker when I turn it on, but no boot happens. I reinsert the battery and it goes into a preboot sequence but that crashes when it tries to initialize the battery, and we go back to the keyboard flicker loop. (Which is all that happens when I try to boot without the battery altogether.) It's four years old, so repair likely isn't a realistic option. All historical work is on indefinite hold. Transcription is just not feasible on a smartphone. I apologize for this.

-

Naoki Otsuka and the Early Years of NJPW

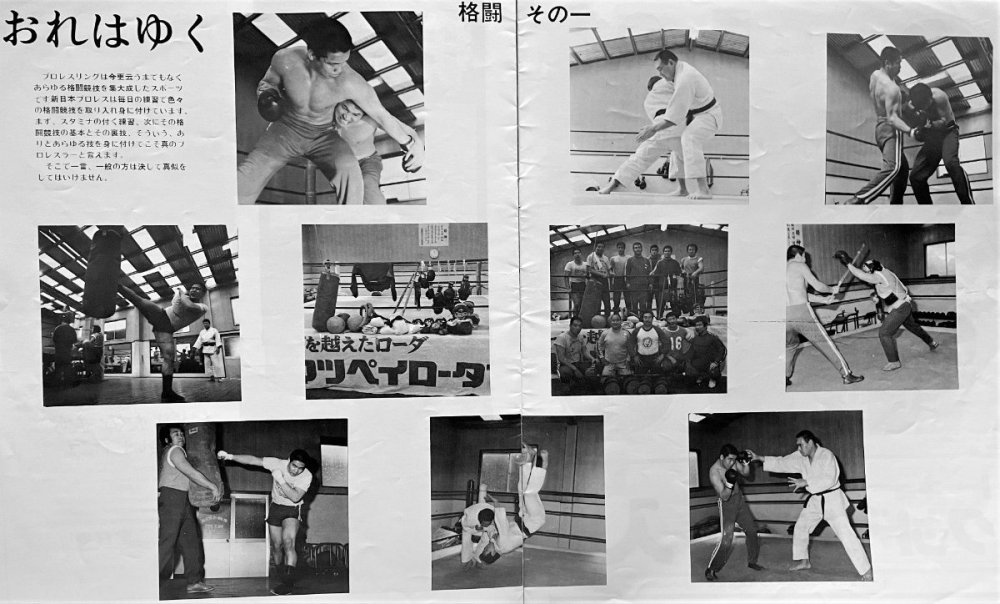

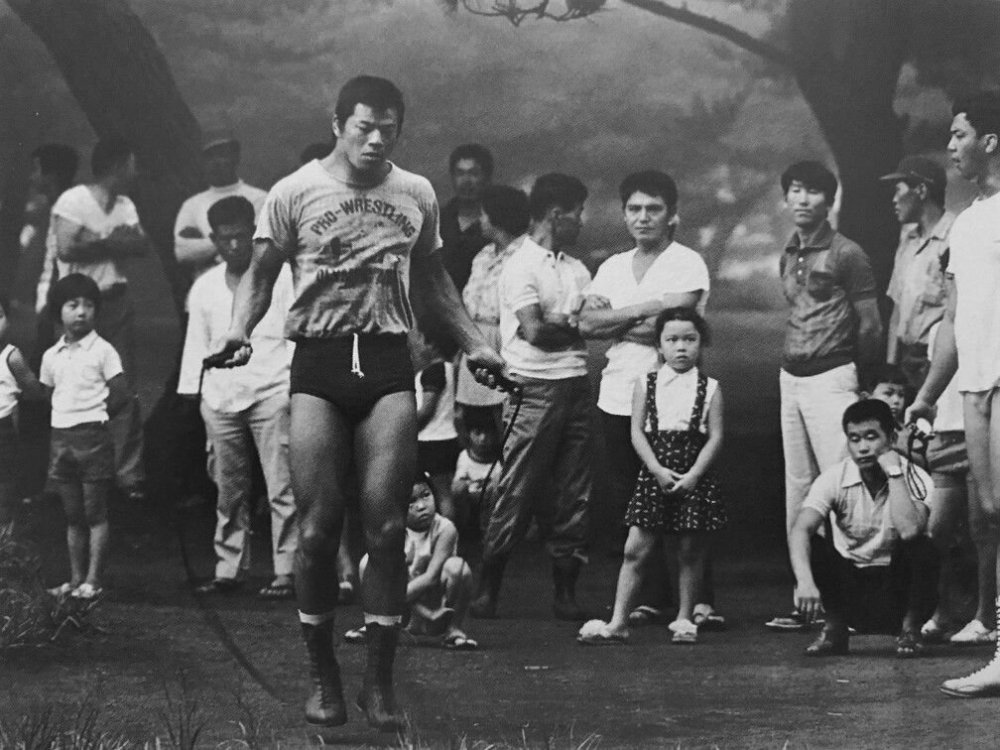

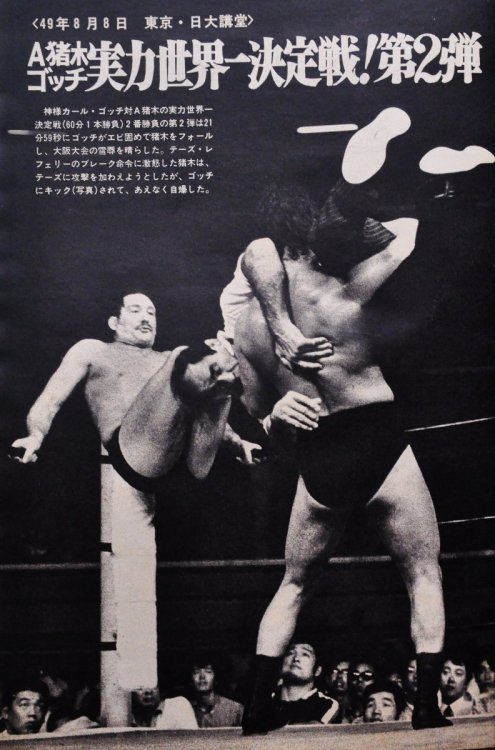

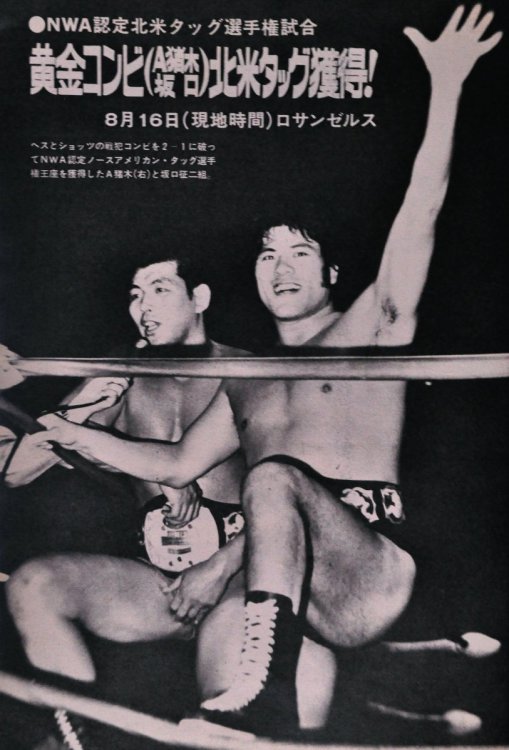

Much of the direct testimony I have on the life of an early young lion comes from a 2019 interview with autumn 1972 trainee and current dojo custodian Kuniaki Kobayashi. I would like to expand this post if and when I acquire more testimonies and resources. The next post will finally return to the main narrative and cover the last third of 1974, but it may take a while, as I would like to transcribe a resource I have about Kintaro Oki: namely, a 2019 interview with his former valet Masanori Toguchi (Kim Duk). LIFE WITH THE LIONS (INTERLUDE #3.3) January 29, 1972: Kotetsu Yamamoto, Yusef Turk, Osamu Kido, Antonio Inoki, and Tatsumi Fujinami drink from a ceremonial barrel of sake at the NJPW Dojo’s opening. NOGE DOJO In 1971, Antonio Inoki and Mitsuko Baisho bought a mansion in Tokyo’s Setagaya Ward, near the Tama River. It had previously belonged to enka singer Midori Hatakeyama, and according to Naoki Otsuka, the property had been brought to Inoki’s attention by Hiroshi Iwata. Otsuka recalls that the house was said to be haunted, due to a rumor that a maid had committed suicide during Hatakeyama’s tenancy. The couple had originally bought the property to live in, but as the late Yoshihiro Inoue put it, “Inoki had no land, so he destroyed his house”. After the mansion garden, with its pine trees and carp pond, was cleared “overnight”, New Japan’s dojo was built. Kido Corporation, run by Osamu's father Yoichiro, was contracted for this task, although Yoichiro used his connections to have other companies assist. During this time, Tatsumi Fujinami’s training consisted of construction assistance, such as picking up pebbles and carrying steel frames, as well as running along the river. The dojo would be a single-story wooden building with 48 square meters of floor space. As mentioned in #3.1, Kotetsu Yamamoto paid for the ring, which was constructed at Kamata Ironworks in parallel with the dojo. (in a 2022 interview, Fujinami speculated that Yamamoto had measured the ring at the JWA dojo before he was fired.) The Noge Dojo was opened on January 29, 1972, at 4:00. In a traditional ceremony known as kagami biraki, the four wrestlers and Yusef Turk broke a wooden barrel of iwai-zake with wooden mallets. After drinking the ceremonial sake, they held an open practice session. While Osamu Kido split his time between the dojo and his parents’ house, the young lions otherwise lived in the mansion, each with his own room. Inoki came only once or twice a week, but Yamamoto was at the dojo every day. Awaking at 8am, the lions would practice for three hours starting at 10. After that, they ate chanko together and were free for the rest of the day. Curfew was 9pm, but Kobayashi admits that none of them observed it. Kuniaki notes that he thinks it is harder to be a young lion now than it was in this early period, because the much larger number of senior wrestlers gives them so much more chores to do. Kobayashi claims he was never bullied, and that all his senior young lions were kind men, even if Hamada “used him a lot”. Kuniaki is called Sanpei by his seniors, which was a nickname that Toyonobori had bestowed upon him, one which Kobayashi feared he would be made to wrestle under. Kotetsu Yamamoto needed to produce talent quickly, and he was already a conditioning fiend, so the physical demands he made of young lions were great. Kobayashi was blindsided by the 1000 Hindu squats per day, as he had only been doing one to two hundred. One day, Yoshiaki Fujiwara asked Yamamoto if he could perform a reduced number of squats due to a knee injury suffered the previous day. When this was refused, Fujiwara briefly became fixated with murdering his coach and practiced stabbing Yamamoto with a kitchen knife on a birch tree just outside the dojo. (Even Akira Maeda, who entered the dojo half a decade later, remembers the marked tree.) Another case that Kobayashi recalls was when Yamamoto made Hamada perform bump drills when he complained of stomach pain, which he would find was due to appendicitis. I am not equipped to untangle kayfabe from reality when it comes to the matter of NJPW’s sparring, but I can’t write this post without acknowledging it. A 2021 blog post about a 2014 NJPW-licensed book quotes a plausible testimony from Motoyuki Kitazawa. Kitazawa states that New Japan’s sparring had its roots in the gachinko (literally “cement”: equivalent to shoot) training of the JWA, and long preceded Karl Gotch’s coaching tenure. When Rikidozan was in charge, the dojo practiced joint-based submission sparring called kimekko, in which wrestlers received instruction from Kiyotaka Otsubo. But according to Kitazawa, this "was not something noble like sparring in the dojo”. Those who could not adapt to kimekko would “never be recognized as professional wrestlers”, and in essence, Kitazawa and others were toys to be experimented on and crushed by the older wrestlers. Those who couldn’t handle it ran away. When Gotch coached for a year (for which he made Otsubo his assistant), he expanded the kimekko tradition not just with new submission holds, but with rougher methods of escape, such as elbows to the back of the head and finger thrusts into the anus. Kobayashi says that Fujiwara was the best of the first young lions at sparring. The young wrestlers who followed Sakaguchi from the JWA were assimilated into the fold, but Kotetsu stoked his lions’ competitive spirit: “Don’t you ever lose to them!” Ozawa was the best of the ex-JWA trio at sparring, due to his size and sumo experience, but Fujiwara always came out on top. There was a substantial pay gap between Kobayashi and those three, whose salaries at least quadrupled his ¥50k per year, but they went out to eat and drink with the rest of the roster from the start. Yamamoto once quipped that those in the JWA who hated practice had joined AJPW, and later criticized Jumbo Tsuruta for allowing himself to develop such a stomach (while giving Shinya Hashimoto a pass because of his constitution). Later on, he would acknowledge that the Four Pillars had excellent conditioning but still criticized the AJPW curriculum for its lack of sparring. As I mentioned in my profile of Masio Koma, All Japan’s original head coach had been good friends with Yamamoto, and the two had talked shop about their training methods before Masio’s death in 1976. I believe Kotetsu’s comments should also be considered in that context, as the Great Kabuki has claimed that Koma’s original curriculum had retained some gachinko training, but that this was lost due to the subsequent influence of the Funks. (I would like to track down interviews with Onita or Fuchi to see if they did any kimekko in the first years of their career.) Kobayashi contrasts Yamamoto’s “scary” personality with Inoki, who did not use corporal punishment in the dojo. Notably, Inoki also did not force young lions to drink alcohol, as Rikidozan had made him do as a teenager when meeting with sponsors. As for Gotch, Kobayashi praises him as a teacher. Karl did not ignore the students who struggled, and taught everyone as an equal. Gotch preferred natural exercises to bodybuilding, and on top of squats and pushups he had young lions climb rope. When Mitsuo Yoshida joined the company, he trained as a young lion. This contrasts sharply with how Tomomi Tsuruta was brought into AJPW. As Tsuruta completed his baccalaureate in the five months after his signing, he received basic training from Masio Koma, who was assisted by Akio Sato. Yoshida only wrestled one match in Japan before leaving for the States alongside Gotch. IN THE RING The 1979 Monthly Pro article describes Kotetsu watching the prelims at a seat out of sight with a notebook in his hands. The ideal for a preliminary match was consistent with Rikidozan’s: essentially, amateur wrestling with a bit of color. There would be corporal punishment backstage if you stepped outside of these parameters. Kobayashi recalls that he was punished by Inoki for a match with Arakawa in the Adachi Ward Gymnasium (possibly early 1975), where the two had gotten into a strike exchange and excited the crowd. When interviewer Kagehiro Osano points out that Fujiwara lost many of his matches by “backbone folding”, Kobayashi explains that that was what we know as a camel clutch. Little Hamada was given special permission to use a dropkick due to his short stature. Yamamoto also fined wrestlers for poor matches. Kobayashi remembers that he lost ¥3000 every time he wrestled Arakawa. One time, Kobayashi was forced by Inoki to do a thousand squats after a stinker against him and did them with frustrated tears in his eyes. Kotetsu would also implement a ¥5000 bonus for good matches, which Kobayashi says he always received when working with Satoru Sayama. Others Kuniaki praises include Kitazawa (“He brought out something in me, or rather, he let me wrestle properly”) and Haruka Eigen (“He was easy to work with and knew how to excite the crowd”), the latter of whom joined NJPW upon his return from excursion in October 1973. Poor performances ran the risk of corporal punishment. In a 2022 interview, Fujinami recalls that Inoki came to the ring and beat him with the shinai during a stinker against Fujiwara. The match continued afterwards, but as Tatsumi recalls, he was less focused on either his opponent or their audience and more concerned about "whether the door would slam in the waiting room". Fujinami claims that Kazuo Sato was a frequent recipient. Kobayashi cites an example that the cards I could find don’t totally match up with. He specifically claims that this happened in a match between Arakawa and Masanobu Kurisu, and that both men’s parents attended the show. Inoki came into the ring and beat them both, but the way he says it doesn’t quite line up with the records. He says it was in their hometown of Izumi, and specifies that they were wrestling against each other, but neither of the Izumi shows from the era had them in the same match. He could be referring to one of two singles matches in Kagoshima city from 1975, or to a myriad of other singles matches. Arakawa and Kurisu would wrestle each other numerous times, and due to their shared hometown, this match would be nicknamed the Kagoshima Championship. (Arakawa’s 1979 Tokyo Sports show match against the IWE’s Snake Amami, a fellow Kagoshima native, also received this nickname.) A section in New Japan pamphlets called Ore wa yuku! (“I’m going!”) was dedicated to young lions. This example is from the 1976 Big Fight Series. In autumn 1974, NJPW held the first Karl Gotch Cup during the Toukon Series. The ancestor of the infrequent Young Lion Cup ended when Fujinami defeated Ozawa. In June 1975, nine lions became five. Fujinami and Kido left for West Germany, while Hamada and Hashimoto went to Mexico. Kobayashi confirms that Hamada had nearly been fired the month before. At the final show of the 1975 World League tour, held in the Nihon University Auditorium, Hamada and Yamamoto got into an argument over chores in the waiting room. Kobayashi claims he saw Hamada doing chores, but a misunderstanding arose and Hamada’s will was too strong to back down. They stood there arguing over whether he was going to do them until Kotetsu struck Hamada and everyone stepped in to pull them apart.

-

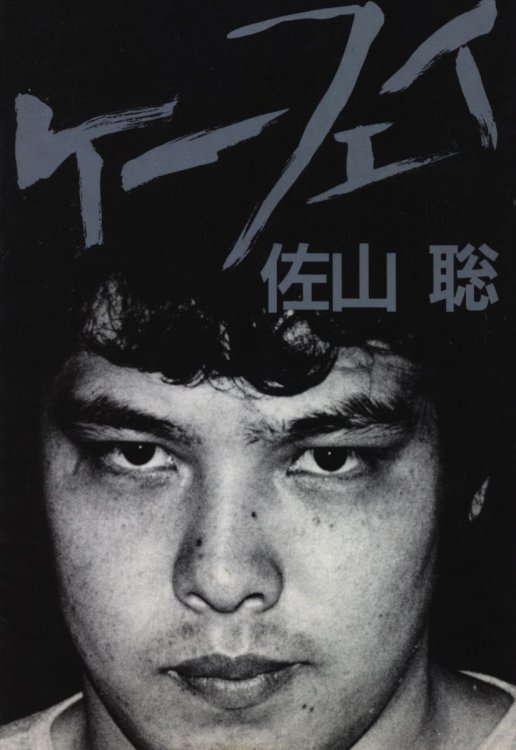

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 25-31, PART TWO [THE FALL OF TARZAN YAMAMOTO]

I don't think I emphasized Tarzan's role in shootstyle's myth enough. According to a book by journalist Joji Inoue (as cited by the excellent Japanese Wikipedia page on Mr. Takahashi's book Bloody Magic), Yamamoto was heavily involved in the publication of Satoru Sayama's 1985 book Kayfabe, for which he wrote the prologue and epilogue. (He may have also suggested the title, a term which we take for granted but which he had to learn from Jumbo Tsuruta fan club president turned overseas photojournalist Jimmy Suzuki.) This was apparently why Tarzan had been banned by AJPW/JPW even before the Weekly Pro boycott. Choshu would later say that Tarzan had been the "U" in UWFi.

-

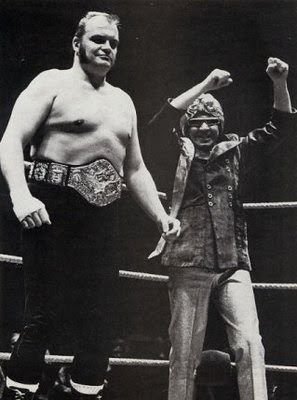

Naoki Otsuka and the Early Years of NJPW