Everything posted by KinchStalker

-

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 25-31, PART FOUR [KAWADA SLUMP, HIROSHI HASE TRANSFERS TO AJPW, 1997 CHAMPION CARNIVAL]

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 25-31, PART FOUR On July 24, Kawada wrestled Albright in the Budokan again. This was not the original plan; as Baba announced the card, Kawada was going to team up with Albright against Misawa & Akiyama. However, Kawada publicly rejected this configuration, stating in a Hawaii interview with Ichinose that he did not want Albright to become fully assimilated into AJPW. On June 29, Baba announced that the match was changed to a second Kawada/Albright singles match, with Steve Williams and Johnny Ace getting the tag title shot instead. On July 5 in Osaka, though, Kawada declared that he wanted their match to be held under UWFi rules. Baba would flatly refuse: “If there’s no pinfall, what do you do? Rule changes? [...] If you do that, wrestling gets smaller.” Ultimately, Kawada lost to Albright in 12:18. Ichinose observes that the way Kawada sold Albright’s 3K Full Nelson Suplex might as well have made it a knockout loss. Three weeks later, Daily Sports carried a scoop. AJPW’s isolationist period was ending, as Baba was willing to negotiate with Nobuhiko Takada. Ichinose mentions the press comments that Kawada made before this development, which are often stated to have led to internal punishment. Kawada alluded to Masayuki Sato’s match report on his #1 contendership match against Kobashi on May 26, in which Sato wrote that Kawada “wanted to have wings”, but knew that that was “an unattainable dream”. Kawada countered that both he and Kobashi had wings, but that they were caged birds. He also criticized his company’s isolationism on business grounds; the policy had been a good idea three years before, but that didn’t mean it could work forever. The common narrative in the West is that Kawada’s slump in 1996 was tied to punishment for his comments, but interestingly, it was already underway by the time he would have said this. UWFi originally wanted to rent Stan Hansen, but he couldn’t work it into his schedule. Kawada’s name came up, and a match with Yoshihiro Takayama was set for their September 11 event at Jingu Stadium. Ichinose covers the match and quotes Takayama’s postmatch comments, in which he said that Kawada “was a bigger man than him”, and that he wanted to fight again in an All Japan ring. Six months later, Takayama debuted for AJPW. Ichinose quotes from the last long interview Baba gave him, which was published in the July 14, 1998 issue of Weekly Pro. Baba invoked puroresu’s incorporation of the martial arts concept of ukemi in his critique of Takayama and fellow ex-UWFi hire Masahito Kakihara. They did not have the “passive training” of pro wrestling. Baba would also say that he wanted AJPW to function as a sort of wrestling school, and Ichinose mentions that the guest wrestlers in late 90s All Japan who tended to do best (read: Hayabusa and Jinsei Shinzaki) played by its rules. From here, we transition to Hiroshi Hase’s November 1996 request to transfer to AJPW. — After representing Japan at the Los Angeles Olympics, Hiroshi Hase joined Japan Pro Wrestling. While JPW indeed had its own dojo, Hase confirms that he (and presumably other JPW rookies such as Kensuke Sasaki) received guidance from Baba in the six months of training before his overseas debut in Puerto Rico. Before shows, Hase would hit the ring for practice sessions which Baba watched from the back. He received advice on how to position and move himself to be visible to both floors of an audience, as well as some ukemi. Of course, when the bulk of JPW U-turned back to NJPW Hase would return to train again in the NJPW dojo. However, Hase does demythologize a common belief about AJPW and NJPW. It’s often believed that the traditional NJPW training method emphasized sparring instead of ukemi, but Hase states that bump drills made up a majority of his NJPW training, even if the movements they taught were a bit different. Ichinose writes that Hase’s ukemi was excellent. It hadn’t always been that way. On June 12, 1990, Hase had taken a Tatsutoshi Goto backdrop poorly; while he managed to finish the match, he entered cardiac arrest backstage and had to be resuscitated. Hase acknowledges that it was his fault, as he had not trusted Goto and had thus taken the move wrong. Nine months later, as he and Kensuke Sasaki defended the IWGP tag titles against the Steiners in the Tokyo Dome, Hase took Rick’s throw-and-release German perfectly, over two years before Misawa brought that move into AJPW. Hase also compares the Three Musketeers’ ukemi to the Pillars. Chono used to be good at it, but (understandably) became more careful after the Steve Austin injury. It was Hashimoto’s weak spot, with Hase going so far as to state that Hashimoto only stood out when he had an opponent who could take *his* moves. Mutoh, meanwhile, had the best ukemi of all three. After Hase had been elected to the House of Councilors, he stayed on with NJPW, signing a one-year contract as an advisor. That had expired in July 1996, after which Hase declared free agency, while stating interest in returning to AJPW. On November 16, Hase came out with Baba after the second match of a Korakuen show, wearing an All Japan jersey. Hase would debut for the company in January, and Ichinose caught him for an interview on December 21, in which he claimed that wrestling in AJPW had long been his dream. Hase would not wrestle any of the Pillars on the eight dates he worked on the New Year Giant Series tour. This would change upon his August return, when he wrestled Kobashi in singles competition. The next month, he would be alongside all four, plus Akiyama, in the Fan Appreciation Day six-man. Hase admits that working against them was “almost scary”, but that the Shitenno were so skilled at taking moves. Hase never tried certain moves near the ropes, as if one’s foot got stuck on the rope while taking a move it would ruin the bump and risk serious injury. However, the Pillars could bump successfully in such situations. Their masterful spatial awareness was also what made their spots off the apron possible. (That was something the Musketeers had never even tried to copy.) Hase praises Misawa’s ukemi most of all. He recalls their one singles match in 2000, and how stunned he was when Misawa, who had no judo background, took his uranage with the proper uke. — After Tarzan’s resignation, Ichinose had declined the editor-in-chief position, but he would take Yamamoto’s place as lead interviewer. So it was that he interviewed Baba before the 1997 Champion Carnival. Baba remarked that the tournament was so much harder now than it had been in the Seventies, when there were only a handful of strong competitors. It was much more grueling now. Ichinose softly suggested that the Carnival could return to the two-block format of 1991-2. Baba’s response was revealing as to the company’s state; the most important factor in All Japan’s success was that they “always gave their all” whether they were wrestling in Korakuen or the provinces. Reverting to the two-block format at this point would lead to decline. Besides, the difficulty of the Carnival only made it more prestigious. Baba said that, thanks to the Internet, the whole world knew about AJPW now. Whoever won the tournament was sure to be labeled the best in the world. The analogy that Ichinose uses to describe the situation is a bus. Baba drove it, while the Shitenno were its tires. The tires were wearing out. The 1997 Carnival was another rough one for Misawa. On March 24, he had his third tournament match against Akiyama in Chiba. While he won the match, Akiyama’s avalanche exploder injured his neck. As the pain spread to his back, he had difficulty sleeping, and his painkiller usage led to frequent stomachaches. This tournament would see him take his first pinfall loss to Kobashi, before the three-way final saw Kawada finally pin the exhausted Misawa in singles competition as well. Kawada’s postmatch comments are exactly what you’d imagine they would be if you saw his face after the victory: “I feel like I only won by the luck of the draw.” After Misawa was helped to the back by Akiyama and Kentaro Shiga, Misawa made no excuses. “Luck is a part of our strength. It’s not like I lost the lottery. I lost the match, and a loss is a loss.” Kawada went on to defeat Kobashi, winning the Carnival and earning the next Triple Crown title match.

-

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 25-31, PART THREE [TAUE & AKIYAMA IN MID-90S]

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 25-31, PART THREE Chapter 27 starts concurrently with the events of the previous chapter, as Ichinose recalls his frustration that he could do nothing as an All Japan reporter to stave off the magazine’s decline. Back in 1991, when Weekly Pro had lost access to SWS, their coverage of the Super Generation Army, particularly Kawada (who got one Weekly Pro cover a month from March to August), had helped keep them afloat. Unfortunately, there was no equivalent to 1991 Kawada in 1996 AJPW. This chapter concerns itself with Taue and Akiyama. —- The 1996 Champion Carnival saw Taue defeat the returning Steve Williams in the April 20 final. When the two had wrestled their league match, though, it was a stinker. On March 26, they wrestled to a draw in Nagano-Suwa. After the match, Baba called in Taue alone and scolded him for his poor performance. As Taue recalls, Baba wasn’t scary. He didn’t hit you, and he didn’t even talk a lot. But when he scolded you, you listened. Taue’s performance in the final would satisfy Baba. The next several pages meditate on Taue: his relationship with Baba and how he compared to the other Pillars. Unlike the other three, Taue had not been a wrestling fan. He stuck with the business because he had a family to support; it was either that or driving a truck. It feels like this part of the book is retreading old ground, or at least spelling out things that already felt established. Stuff like how Taue never tried to add a signature strike to his arsenal unlike the other three, or how he felt that his sumo training gave him a certain pride even if he didn’t share the other Pillars’ temperament. Taue doesn’t bring up the famous bench press story, but he mentions a couple episodes with Baba, such as when the woman who lived in Baba’s Hawaii mansion for most of the year mistook him for his son, and the time when the hood of Baba’s Cadillac bonked him in the head in the Hawaii rain, while Taue tried to stifle his laugh. The first thing that comes to mind from the peak period of Taue’s career, though, was the cars he bought. He liked American full-tuned cars “that were so stupid that he now wondered why he drove them”. He also returned to driving school around this time when he caught the urge to ride a Harley. Taue won the Triple Crown from Misawa on May 24, in what was his fourth attempt. His only successful defense came against Kawada at the end of the tour. The two had not wrestled a singles match outside of the Carnival since 1992, and the match was considered a deflating affair. Ichinose recalls his amusement at Akira Fukuzawa’s naive declaration that the match was still in its early stages, fifteen minutes in. Ichinose quotes the Weekly Pro writeup: “One of Kawada's mottos is that ‘pro wrestling is not just about techniques’, but on this day, Kawada was just about techniques.” After the match, he writes that Kawada sat sadly in the dressing room, “like a puppy in a pet store”. Kawada ruminated on his slump, saying that he felt “less dangerous” than he had been five years before. If All Japan was a school, he had been trying to be an honor student, and that had made him weak. Furthermore, he stated that he thought the audience wanted to see something fresh. While the Holy Demon Army would ultimately remain together until the NOAH exodus, these comments clearly teased a possible Seikigun breakup; Kawada’s theory of wrestling as a three-year cycle comes to mind. — From here, the book transitions to the subject of Akiyama’s promotion to Misawa’s primary tag partner. The next few pages lay his angst bare. When Akiyama pinned Kawada to win the AJPW World Tag Team titles on May 23, it was his second victory over a Pillar; he had pinned Taue in a January six-man. However, when Akiyama was handed the belt he refused to wear it. He stated in postmatch comments that he did not feel he could wear the world tag belt while he was still chasing the shadows of Kobashi & Kikuchi, as the then-All Asia tag co-champion with Takao Omori. Ichinose supposes that Akiyama was not in the position to tell the press not to put him on the Pillars’ level, but he is still ashamed in retrospect that he did not notice how deeply it wore on him. In the early 2000s, Ichinose learned that Akiyama had been suffering from an anxiety disorder since the mid-90s. As early as an interview at Ikegami Honmon-ji temple in February 1996, Akiyama recalls sweating profusely during an interview with Ichinose, although Akiyama successfully covered it up as his being embarrassed about the question of his recent marriage. He was too ashamed to tell anyone, but the wife would pick up on the husband’s struggles. Akiyama recalls a panic attack he suffered while taking a shower; while it had subsided by the time he heard the siren of the ambulance he had asked his wife to call, the incident made him afraid to bathe. The bullet train and airplane became dreadful experiences, with Akiyama pinching his inner thighs to cope with flights. His high-profile singles matches on top of his title defenses often ruined his ability to sleep. He even recalls a panic attack that struck during a televised match (on July 16, 1999, against Yoshinari Ogawa). This chapter ends with Akiyama’s appreciation of Kawada. While the persona he developed was a genuine expression of himself, the book observes that he developed into a Kawada-like presence in NOAH, and Akiyama himself states that, through wrestling against them, the rhythms of Kawada, Taue and Fuchi became imbued in him, not those of Misawa and Kobashi.

-

Kintaro Oki

Probably the 1975 one at the Rikidozan Memorial show. It's absolutely effective at what it is. It's not the one that I have a pin-up of, though. Mulling over putting this up.

-

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 25-31, PART TWO [THE FALL OF TARZAN YAMAMOTO]

(2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 25-31, PART TWO (THE FALL OF TARZAN YAMAMOTO) A 1995 episode of TV Tokyo docuseries Navigator profiles Tarzan Yamamoto. However mixed the response had been to Takashi “Tarzan” Yamamoto’s promo segment with Shinya Hashimoto at the end of the Bridge of Dreams show, his public profile had not diminished. His appearances ranged from a weekly column of horse-racing predictions to his weekly radio show, and even a variety show appearance. While the character itself was not based on Yamamoto, the fact that the protagonist of Fuji TV drama Itsuka Mata Aeru (played by Masaharu Fukuyama) was a magazine editor reflected Tarzan’s influence in popular culture…especially since Fuji’s production staff had visited Weekly Pro’s office for research. On February 9, 1996, Weekly Pro received a notice from WAR. Signed by director Masatomo Takei, the letter stated that it would freeze coverage from the publication. It read that the boycott was not so much against the publication as it was against its EIC, Yamamoto. “There are so many reasons for our decision that it is difficult to specify, but I can say that we decided to do this in order to create a stir in the development of WAR and the wrestling world.” WAR had initially inherited SWS’s Weekly Pro ban, but had lifted it in January 1993. The next two years saw friendly relations between promotion and publication, with Tarzan even getting an interview with Tenryu. However, the relationship had deteriorated as talks concerning WAR’s participation in the Bridge of Dreams show broke down, something which I have already covered. Until this point, though, the reporter on the WAR beat continued to produce match reports and attend press conferences without issue. On March 16, another letter came in. NJPW had followed WAR’s lead. — As Ichinose recalls, this had been rumored for a week. A few days earlier, a fan wrote in asking if Weekly Pro was going to be banned. As this fan had learned, New Japan had sent contracts to local promoters to secure their loyalty. In these contracts, they stated they would soon boycott the publication, and asked the promoters to keep in line with them even if they had personal connections to Yamamoto and the staff. Furthermore, an unnamed member of NJPW’s front office had called the office in December to let them know that NJPW, UWFi, and WAR were planning to join forces in a three-pronged boycott. While the letter bore NJPW president Seiji Sakaguchi’s name, Yamamoto was convinced that its true author was Riki Choshu, who is quoted as having once publicly stated that “Yamamoto should not be in this world.” Tarzan would strike back in a series of issues. In one, he claimed that the conflict between him and Choshu stemmed from Choshu’s disdain for mixed martial arts. Yamamoto expressed disappointment that Choshu had banned NJPW talent from pursuing the sport on the side, as it flew against the Inokian ideals of yore. (Note that, if comments Ichinose made a little earlier in the book are to be believed, Yamamoto had also played a role in building up the mystique of the UWFi. If so, he was not only complicit in shoot-style’s successful working of the Japanese fanbase, but like his editorial predecessor Hideo Sugiyama with the original UWF, he was a knowing component of it.) Choshu had fiercely opposed Weekly Pro’s discussion of K-1 in a September issue, but now, the magazine had no choice but to also cover MMA. On the April 9 issue’s cover, Tarzan asked Inoki what he thought of NJPW’s refusal to grant interviews, while the issue itself contained an interview with K-1’s Kazuyoshi Ishii. It was the April 16 issue, though, where Tarzan really bared his fangs. In an editorial, he wrote that for all the supposed depth of New Japan’s roster, it had declined into character-based wrestling. The likes of Chono and Tenzan worked “obvious” matches, and even Choshu’s work had declined. Furthermore, younger talent such as Satoshi Kojima had done nothing *but* character wrestling. The thrust of Yamamoto’s critique was that, once a character had been established, a wrestler did not have to concern himself with the content of his matches. This was the difference between New Japan and All Japan. While AJPW had to win provincial audiences over with substantial matches, NJPW was content to provide nothing more than character-based “local entertainment”. The headline of this piece read that New Japan was thus “cutting corners” in their provincial shows. As Weekly Pro’s NJPW reporter, Masayuki Sato, has claimed, the roster was not united behind Choshu’s opposition to Yamamoto at first…even if Chono had grilled Sato for working for “Yamamoto Weekly” in March. But Tarzan’s response to the letter had cost him any sympathizers he may have had in that locker room. Ichinose believes that his magazine’s response might not have been so caustic had deputy editor Kiyonori Shishikura, who I have previously cited as a tempering influence on the publication, not been hospitalized at the time. Anyway, Ichinose was actually confident that Weekly Pro would triumph. While they had been on a slight downward trend, they were still selling over 200,000 issues a week. Neither the AJPW/JPW boycott of 1986 nor the SWS ban had sunk the magazine, so they thought they could weather the storm. NJPW was a little worried too. World Pro Wrestling commentator Katsuhiko Kanazawa, who was hired through Weekly Gong, is quoted recalling that Katsuji Nagashima, NJPW director and right-hand man to Choshu, had asked him to keep him posted on Weekly Pro’s circulation figures. Kanazawa recalls that Gong were worrying about their own sales at the time, and while EIC Kagehiro Osano resolved to cover New Japan fairly without special treatment from Nagashima, Kanazawa was inspired to produce a studio special with Keiji Mutoh and Kensuke Sasaki, being interviewed in character as the Great Muta and Power Warrior. That issue sold very well, and in the coming months, Gong would finally surge ahead of Weekly Pro. Meanwhile, Koji Kitao’s Takeki Dojo banned Weekly Pro in early April. Finally, UWFi gave a notice of its own in late April, having been savvy enough to hold off on banning them just long enough for Weekly Pro to run their ads for the April 29 Tokyo Dome show. Above: the author of this very book oversaw the bold, text-based special issue covering NJPW Battle Formation on April 29, 1996. For the only time in his career, Ichinose would be in charge of a full issue of Weekly Pro: the special issue covering that very event. Having no photographic access to the show, Ichinose conceived a bold, fully text-based issue. His fellow reporters and freelance affiliates all signed on, with each covering one match on the card. The Great Muta/Power Warrior match even saw writers Ken Suzuki and Kazuhiro Kojima write pieces from the perspectives of each character. Yamamoto did not attend the show, but wrote about his own thoughts as he sat outside the Tokyo Dome that night. Shishikura had not fully recovered, but he came through to proofread the issue. As Ichinose puts it, the Battle Formation special issue was the last hurrah of the Yamamoto era. It sold over 50,000 copies, which was considered a success to some extent. But it hardly damaged New Japan. While Weekly Pro managed to keep their sales about 100,000, the blow was severe. Yamamoto admitted defeat, as the June 11 issue featured an apology for the April 16 editorial on its front page. With the July 23 issue, Tarzan resigned. After this, Yamamoto phased out of his role as a creative consultant for Baba, although their relations were still good. The bans were all lifted, and New Japan was quick enough to allow them access in time to cover the G1 Climax. Weekly Pro’s sales would recover enough to take their place above Gong, but they would never sell over 200,000 copies of an issue again. — As this is the last time Yamamoto figures into this story, I think he deserves a few words. Ichinose appears to have remained friendly with him over the years, and clearly maintains a respect for his maverick nature. But not everything Ichinose reveals is flattering. The magazine had hired female writers before, but the Yamamoto era featured an all-male staff. Women were not even hired for freelance work, with many applications rejected because Tarzan thought that “it would upset the magnetic field”. (I would make a Susan Anway-era Magnetic Fields joke had she not recently passed.) Ichinose recalls that, for a period, he dated a woman who he had met on the 1991 Misawa cruise, but took great care not to reveal this or “his flirtatious side” in general to his boss. The boys club era of Weekly Pro had certainly overstayed its welcome by 1996, and this information seems to contextualize an incident Ichinose mentioned earlier in the book, in which he caught heat for encouraging Cuty Suzuki and Mayumi Ozaki to remove their bras and cup their breasts in their hands for a Saipan photoshoot in 1993. Ichinose recalls that the women, who had already done gravure work at this point, raised no objection to his request. But it still feels like a call better made by a female photographer, and one totally understands why JWP may have reacted as they did, especially if they have context on Weekly Pro’s all-male makeup. Yamamoto even used his power once to take a job opportunity from Ichinose. Ichinose was hired to do commentary work for WOWOW’s JWP program, but when he wrote in Weekly Pro that these commitments would not allow him to personally cover every event in the 1993 RWTL, Tarzan forced him to quit. Ichinose’s dad had bought a WOWOW subscription just to hear his son, and it was so quickly snuffed out. But whatever one thinks of him, Tarzan himself was one of Heisei puroresu’s most interesting characters. For better or worse, he should be better known among Western fans.

-

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 25-31, PART ONE [1995 CHAMPION CARNIVAL, REST OF YEAR]

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 25-31, PART ONE This is the start of a series of posts on the last part of the Ichinose bio. I'll be putting each one out as they're ready, as I think I've kept you all waiting too much. Overall, this stretch of the book is not as insightful on All Japan as what came before, leaning on contemporaneous interviews to flesh out the wrestlers as characters and possibly reflecting Ichinose's diminished role as a creative consultant. That could just be my burnout on this particular book talking. Whatever the case, I'll summarize the last stretch using whatever piques my interest. — 1994 had seen a decline for the company. Ichinose cites the November 24 show at the Okayama Budokan as an example. The previous year, the RWTL show in the venue, which was headed by a Chosedaigun/Seikigun six-man, drew 3,050. Meanwhile, this show, which was headed by a tournament match between Misawa/Kobashi and Akiyama/Omori, only drew 2,300. This decline led Baba to consider booking “A-rank matchups” consistently, as if it were a singer performing a tour with a single setlist. Ichinose pointed out that this was unrealistic, and Baba’s “experimental and innovative” idea was never implemented, but 1995 did see an interesting shift. Starting with the New Year Giant Series, “A-rank matchups” were scattered across the country: The Kobashi/Williams singles draw in Oita, the famous Kawada/Kobashi Triple Crown defense in Osaka, and the Misawa/Kobashi vs. Kawada/Taue tag title defense in Yamagata. The timeslot cut of the previous year also influenced this shift. While AJPW’s television presence was buttressed by broadcasts from local stations such as TV Iwate, the primary AJPW Relay program would not be restored to an hour, even when it was moved to Sundays in the spring of 1995. As Ichinose puts it, the program no longer had the ability to convey serial drama. This would lead local fans to be considered before “distant viewers”. Let’s now jump ahead to the 1995 Carnival. On April 6, AJPW returned to the Okayama Budokan. This time, they gave the venue the biggest matchup they could: a tournament match between Misawa and Kawada. This match, of course, is infamous for the broken orbital bone Misawa would suffer from a Kawada kick, as this shoot injury would provide material for months of matches. A doctor recommended he stop, but Misawa refused. The Kawada match would be the first of three tournament draws, with the next two coming against Hansen and Taue. An April 8 win against Akiyama, which Misawa got by submission with the reverse nelson deathlock he had debuted during this tour, brought his tally to seven wins and three draws. Meanwhile, this tournament also saw a resurgence for Taue. After two years of failure to get past Kobashi in the Carnival (a loss in 1993 and two draws in 1994), Taue defeated him in their first tournament match. In February, Taue had added the throw-and-release German suplex and the Dynamic Bomb to his arsenal, and during the Carnival he debuted the “Cliff Nodowa” apron chokeslam. The tournament and the tour ended at the Budokan on April 15. Ichinose doesn’t mention Aum Shinrikyo’s threats to attack both the Budokan and the Tokyo Dome with sarin gas that day, but as the April 24 Observer states, neither incident materialized as spectators were thoroughly searched. As his mentor Jumbo Tsuruta sat in on commentary, Taue unleashed the maneuvers he had developed over the past few months. None of them were enough to keep Misawa from winning his first Carnival. The backstage ritual of pouring beer over the winner’s head was modified to accommodate Misawa’s injured eye. — “If I could get rid of it by talking about it, I would. There's no point in talking about something that only you can understand, you know. Once you've decided to wrestle the match, there's no point in protecting your eyes, and there's no point in being depressed. [...] If it could be cured by saying, "It hurts, it hurts," I'd say it a hundred times.” Ichinose mentions an interview he conducted with Misawa after the tour. I want to mention this because he brings up a postcard that Weekly Pro had been sent. The reader criticized Misawa for not showing weakness even when injured, and expressed his wish for Misawa to expose his vulnerabilities. Misawa’s response and Ichinose’s meditation on it makes it clear that Misawa’s stoicism was a feature for his fans, not a bug. Ichinose writes that Misawa’s aesthetics made him reflect on himself, and while Misawa was not so grandiose as to offer these nuggets as “life lessons”, Ichinose recalls that his words “penetrated” people and offered them guidance. Ichinose also peeks behind the curtain to show us that Misawa was not always so composed. Ichinose would brighten up Misawa’s days by bringing him the latest issue of Weekly Shonen Jump before it circulated into the regions where he was working. The smile he saw when he gave Misawa one of those issues was a carefree one, unlike that he saw when he gave Misawa an issue of Weekly Pro. He also mentions that Misawa’s bawdy sense of humor, which would threaten to undermine his stoic reputation in the NOAH era when it came out in variety show appearances, was already on display when a female reporter was among the press circle. Above: Misawa, Kobashi, and others appear on the NTV variety show Super JOCKEY. In May, Baba began allowing AJPW talent besides himself to appear on variety shows to promote the product. I do not know when he had started banning others from doing so; Jumbo made plenty of these appearances in his day, and I recall that Rusher Kimura had been a celebrity judge on a music program. This is something that I would ask Ichinose about if I had the opportunity. (I wonder if Baba’s experience with Thunder Sugiyama, who pivoted into a part-time career with television gigs before falling out with him over money, might have influenced his policy.) The Super Power Series’ main match was considered the May 26 Triple Crown match in Sapporo. 5,800 came to see Misawa start his second reign with a victory over Hansen, which was a strong number but below the highest gates they had drawn in the building earlier in the decade. As for the famous 6/9/95 tag match, the book doesn’t offer much beyond stating the result, pointing out that the match won the Pillars the Best Bout Award, and reproducing Kawada’s postmatch comments, which were prideful but still respectful of Misawa. Ichinose brings up some incidents in mid-95 which suggested a stylistic development in the house style. First, in the June 30 start-of-the-tour Korakuen six-man, Misawa startled observers by giving Kawada a regular-style powerbomb when his attempt at a Tiger Driver was resisted. Ichinose ascribes a significance to this moment, as Misawa was not one to use other’s moves, or at least he hadn’t been since the Tiger Mask II days. “Something about Kawada made him abandon his aesthetics.” The following week, during a six-man on July 8, Kawada choked out Misawa with a sleeper early on. Ichinose cites these matches, as well as the Triple Crown match they built up to, as examples of the “deepening pro-wrestling” between Misawa and Kawada, which had a different character than the matches Misawa would have against Kobashi. The imagery Ichinose uses to evoke Misawa vs. Kawada is a drill descending into the earth until it reaches the magma. Ichinose recalls asking Misawa after the match and standard postmatch interviews whether he felt wrestling like that was shortening his lifespan. Misawa replied that he felt he could die at any moment, referencing pokkuri (the Japanese term for what we may call sudden adult death syndrome). Kyohei Wada has recalled another story about this match. As Misawa suffered a concussion during it, he had lost his memory of working the match as soon as he returned to the locker room. Upon removing his ring shoes, he began to lace them back up to return to the ring, until Kyohei told him the match had already happened. — At some point in July-August, Gary Albright of UWF International stated that he wished to compete in All Japan. Baba responded on August 23 that any foreign talent was welcome to work for him, but that AJPW did not do business with other organizations, to one of whom Albright was still contracted. Ichinose contrasts Baba’s fidelity to procedure and formality with the October 9 NJPW/UWFi Tokyo Dome event, which he claims happened due to a single phone call between Nobuhiko Takada and Riki Choshu. The August 23 event at Odate was just supposed to be a minor show. Ichinose attended because he wanted to see Masao Inoue team for the first time with Kobashi, as well as have his first match against Hansen. Little did Ichinose know that this match would become infamous for the beating Hansen gave Kobashi with his bullrope. Kobashi used Hansen’s trademark weapon against him, and the bad man from Borger *snapped*, punishing Kobashi to the point of severe bleeding from his left arm. Ultimately the native team won the match when Richard Slinger got disqualified, while Kobashi impressed with his postmatch antics. He looked to be on the verge of tears at times, but he grabbed a chair from the audience and rushed back to the foreign locker room to attack Hansen back in a brief brawl. Misawa said he couldn’t even concentrate on his own match ahead. As Kobashi headed for the ambulance, he repeatedly darted glares back at where Hansen was supposed to be. Fortunately, there was no damage to the bone, but the local doctor said the wound would require 22 stitches, as well as rest. However, Kobashi refused to take dates off. That night, Ichinose and Kobashi went out for a very late dinner, where they were joined by Kawada. Ichinose had the latest issue of Weekly Pro, in which Albright had stated his intent to move to All Japan. An inebriated Kawada who was excited by the prospect let it slip that, if Albright were to jump ship, he wanted to be the first to face him. The next day, Ichinose told Baba about this, and it seems that he got grilled for it. Ultimately, Baba announced on September 15 that Albright would participate in the October tour, and that Kawada would face him at the 10/25 Budokan date. When Baba remarked at the press conference that someone had told him Kawada wanted a crack at Albright first, Ichinose recalls breaking out in a cold sweat. Meanwhile, Kawada stated that he would be willing to fight Albright under UWFi rules. Sure, this was partially meant as a joke to play off of the confusion at the time over what rules the NJPW/UWFi matches would be held under, but Kawada was serious about this. (For what it’s worth, as early as the September 4 Observer, it was being reported that Albright was expected to join AJPW as Hansen’s new partner in October.) Ichinose goes on to talk about that match, as well as Kobashi’s first Triple Crown shot against Misawa, but as he draws the chapter to a close, what most occupies his mind is not the 1995 RWTL, but an incident as that tour began. On November 11, Ichinose had finally gotten an interview with Yoshinari Ogawa, who had won the AJPW Junior Heavyweight title in September. That interview was published around the beginning of the tour, and it sticks out in Ichinose’s mind because Ogawa came to him to ask about a few lines in the piece: “I didn’t say that, did I?” It turned out that Ichinose had asked Ogawa whether he agreed with a statement, and then put those words in Ogawa’s mouth. Ichinose actually expresses gratitude for this, remarking that while Ogawa is now known as a “nagging and annoying” subject for interviewers, he had made him realize the error of this method, which Ichinose claims he quit using after this. Next time, we cover Ichinose's perspective on the fall of Tarzan Yamamoto and the end of Weekly Pro’s period of greatest relevance.

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

RIP Strong Kobayashi. https://www.tokyo-sports.co.jp/prores/3911135/

-

BROKEN CROWN: THE FALL OF JAPAN PRO WRESTLING, 1971-1973

Awesome! Those two books are definitely on the itinerary. I've got enough transcription work to last me a while, but I may take you up on that when I've worked through all this stuff. Speaking of, I have started work on the last section of the Ichinose Pillars book after much-needed rest. I hope to have something out in January. One last thing, though. I have acquired another book for future transcription. This is a 2004 biography of Sadao Nagata, the box office don who helped manage the JWA in its early years. Only about 150(/500) pages are dedicated to the section about Rikidōzan, but I think transcribing the book as a whole may provide valuable context for the broader entertainment industry. After all, Nagata is basically responsible for letting the Yakuza into the industry proper, through becoming a business partner of Noboru Yamaguchi of the Yamaguchi-gumi in the mid-twenties.

-

Tsuyoshi Kikuchi

Kikuchi himself claims that he wound down his career in the mid-90s out of his own volition. After Jumbo got sick he felt he was at a crossroads, and then he started dating someone. They married in 1995, and soon afterward he asked to be transferred to the Holy Demon Army. He felt that if he stayed in the Super Generation Army he was going to be the punching bag forever because he was never going to break that glass ceiling. So he transferred knowing he wouldn't get booked in the six-mans more than Fuchi, with the eventual goal of winding down with the comedy six-mans. He transferred to the "heel" comedy faction in 97.

-

BROKEN CROWN: THE FALL OF JAPAN PRO WRESTLING, 1971-1973

In a footnote on the full blog post, I go into the old plan for Oki to inherit Rikidozan's stage name. The higher-ups were forced by the underworld guys in the Association to promise to do so once he won the world title; all those guys were involved in diplomacy with South Korea, and they saw this as a potential expansion of business. (Park Chung-hee would bankroll Oki's promotion at home to provide anti-communist, pro-American entertainment.) Thing is, EVERYBODY knew Oki was Korean, and he had immigrated illegally at that, so it would have tanked their image. That helps explain his bitterness too. Now see, the story I heard was that Togo just used Thesz's name to create his Togo & Thesz company. Endo was able to convince NTV to let them shop for a second deal with NET because he planted stories in the press that Thesz really *was* coming to work for the company.

- BROKEN CROWN: THE FALL OF JAPAN PRO WRESTLING, 1971-1973

-

BROKEN CROWN: THE FALL OF JAPAN PRO WRESTLING, 1971-1973

Monday is the 50th anniversary of Inoki's firing from the JWA, which triggered the greatest year of change in puroresu history. I paused Pillars bio transcription to write a four-part series on the fall of the JWA (in which I call the promotion Japan Pro Wrestling, a quirk which I will explain), paralleled by the establishments of NJPW & AJPW, and I am about 85-90% done. Each part will go live on my blog every two days beginning with the 13th, but I want to give a taste of it now. It just so happens that my post on the coup (the second in this thread!) contains some major errors concerning what exactly happened; I misinterpreted the events to mean that Akimasa Kimura had stolen money from the safe, and that that had led to Inoki being fired. I've cut the background section about 1964-69, and this won't have any of the photos or footnotes, but I hope you all enjoy. BROKEN CROWN: THE FALL OF JAPAN PRO WRESTLING, 1971-1973 Part One: The Coup --- --- CRACKS IN THE CANNON: MAY-OCTOBER 1971 THE PLOT: NOVEMBER 1971 THE FALLOUT: DECEMBER 1-9, 1971 AFTERMATH: DECEMBER 13-17, 1971

-

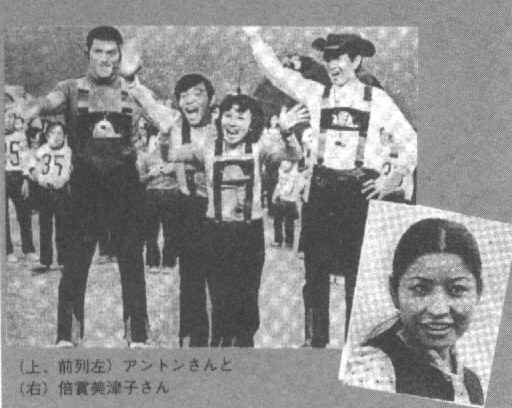

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

I uncovered some very deep and very funny lore while researching my current project. In October 1972, while NJPW was still a struggling independent organization, Inoki joined the cast of a now-forgotten kids show on Fuji TV, which lasted from October until March 1974. "Anton" performed gymnastics and even had a tie-in single released titled "Anton Rhythm". Sadly, no footage has been released, but we have a couple photos and fifty-five seconds of said single.

-

Antonio Inoki

I've been watching some '77 NJPW off and on, and I've seen this formula rear its ugly head all the way back then. The NWF title defenses against Johnny Powers and Stan Hansen are very much in this vein, with his opponent in control on the mat for much of it until Inoki gets a few good shots in for a pinfall.

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

The original NJPW roster. Row by row, left to right (though bear in mind that this was meant to be read right-to-left if the order confuses you): Kotetsu Yamamoto, Toyonobori, Antonio Inoki, Osamu Kido, Katsuhisa Shibata, Motoyuki Kitazawa, Shoji Ito, Little Hamada, Tatsumi Fujinami, referee Youssef Turk, Kazuo Sato, and Shinichi Kihara. Ito, Sato, and Kihara all retired in less than a year, although Ito remained with the company through its sales department until leaving as part of Japan Pro.

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

Is the Baba/Sakaguchi vs. Funks match from the Olympic Auditorium the only Baba footage we have from the NET TV era? Just so we're on the same page, the World Pro Wrestling Japanese Wikipedia page lists four months' worth of Baba matches that were broadcast on the network from April to August 1972, which went against Baba's wishes and led to Nippon cancelling the JWA program. I noticed that he wrestled Johnny Valentine on the first of June. I am working on a four-part retrospective on the fall of the JWA for my blog and thread, to be posted on the 50th anniversary of Inoki's firing (December 13), and this information is relevant to the circumstances behind Baba's departure from the JWA.

-

Antonio Inoki

I stand corrected. My noobness in this community is displayed yet again.

-

Antonio Inoki

A bunch of JWA stuff came out in 2019. It turns out that the big, well-circulated matches from the NTV side of things (Rikidozan/Destroyer II, Baba/Fritz '66, Baba/Destroyer, Toyonobori/Destroyer, etc) all came from a nine-week program of JWA highlights that the network put on after they dropped the JWA program, but while the first episode batch of Taiyō ni Hoero!, the long-running police procedural which would receive the JWA's old 8pm Friday timeslot, was still in production. But while they'd released individual matches from it over the decades, I don't think they'd ever reaired the whole thing until 2019. The Markoff match, important as it was for Inoki, fell victim to that.

-

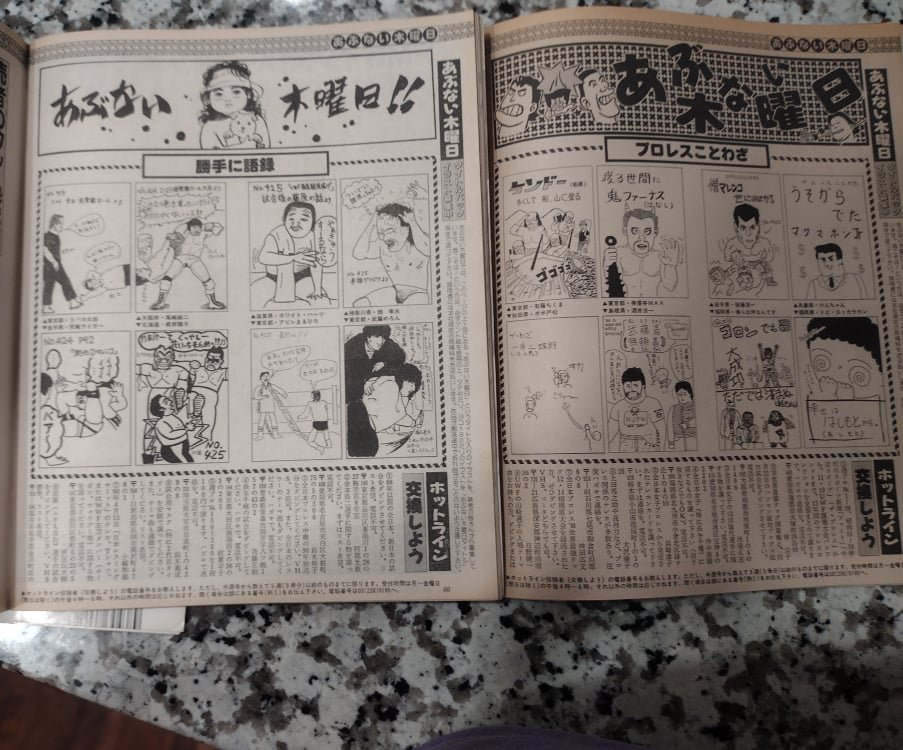

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 22-24, PART THREE [WEEKLY PRO WRESTLING, BRIDGE OF DREAMS SHOW]

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 22-24, PART THREE I think I’m going to keep this post dedicated to the thrust of Chapter 24, which concerns Weekly Pro and the Bridge of Dreams show. Just covering the second and third AJPW tours of 1995 and trying to interweave them feels weird to me, so I’m going to go ahead with scanning and transcribing Part Four and probably include the stuff about those tours in a general post about 1995. ----- In Dave Meltzer’s coverage of Takashi “Tarzan” Yamamoto’s 1996 step down as EIC on the July 8, 1996 issue of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter, he wrote that Yamamoto was credited with bringing Weekly Pro’s coverage “from the Apter-mag level almost to Observer level” by introducing a critical approach. Ichinose frames it *much* differently, which is most likely due to the angle that he is writing from but also provides insight into how it was received. As he puts it, Weekly Pro was always considered a more disposable magazine than Gong, which covered its subjects with an objective, “standard lens” approach set by original editor-in-chief Kosuke Takeuchi.1 Longtime Gong writer (and Jumbo biography writer) Kagehiro Osano is quoted stating his longtime opposition to Weekly Pro’s approach, which leaned into its subjectivity and thus made for a disposable product. Yamamoto puts it as Weekly Pro offering a “telephoto [or] wide-angle” lens to contrast Gong’s standard lens. Although Ichinose indicates that the magazine was leaning in this direction as far back as the Hideo Sugiyama era, Yamamoto embraced it, comparing Weekly Pro’s function to that of a convenience store salad which a salaryman enjoys on their commute, and encouraging all his writers to bring their subjectivity and “freshness” to the forefront of their reportage. For Ichinose, this often manifested in writing about the atmosphere around the show he was covering: “The temperature and air flow in the venue. The smell of yakisoba from the concession stand. The practice before a match. Sweat pouring out of a wrestler. The reaction of the crowd. What happened in the waiting room. The look on a fan's face on the way home. Anything.” Others on the staff liked to express themselves by “using difficult Chinese words”. For all this, though, Ichinose credits deputy director Kiyonori Shishikura’s “Gong-like DNA” (like many of Gong’s hires, Baseball Magazine had hired him from a wrestling fan club) with providing a crucial bit of balance. [EDIT 2022.03.08: Shishikura had not been part of just any fan club: he was one of the four original members of the Maniax in the late 70s. The Maniax were directly associated with Gong and Takeuchi, and even contributed directly to the magazine. They are also famous for shooting (and screening) 8mm film at wrestling shows, some of which later showed up on an IWE DVD box set that was assembled with Takeuchi's cooperation. Later on, fellow charter member Wally Yamaguchi would build a ring in the Maniax office and loan it out to hobbyist group Student Pro Wrestling, in an early example of fan-participation culture in puroresu.] Above: two examples of “Abunai Thursday”, a Weekly Pro page of reader-submitted comics. [Sources: Issues #298 (2/7/89) and #429 (4/16/91)] Weekly Pro did have one advantage over Gong, which was that from the very start of its rebranding as such, it was sold at kiosks in Japan National Railway (now JR) stations. Ichinose made contributions to the magazine with this salaryman audience in mind, such as a “Ticket Information and Spectator Guide” which listed each show venue’s travel time from the nearest station, as well as whether shoes were allowed and whether there were shops (they got this information by calling each venue). Weekly Pro had a Valentine’s Day tradition in which male readers sent postcards in the hope of receiving chocolates from a joshi wrestler. “Abunai Thursday” was a page influenced by Weekly Shonen Jump’s “Jump Information Bureau”, featuring reader-submitted postcard drawings which often lampooned wrestlers. Certain wrestlers would become frequent subjects, such as Shinya Hashimoto for his rotund physique, and Masanobu Fuchi for his perpetual bachelorhood. Both were good sports and enjoyed these comics. (One wonders if this feature was an influence on Akatsuki, an illustrator who draws comic strips about funny old puroresu stories.) Above: Shinya Hashimoto and Tarzan Yamamoto end the Bridge of Dreams show with a promo segment teasing a future show. [Source: Weekly Pro Wrestling Issue #665, dated 4/20/1995 (photograph included in free preview of archived copy)] On November 6, 1994, Baseball Magazine (henceforth BBM) sponsored an NJPW event at Korakuen, at which Tarzan Yamamoto teased that Weekly Pro was going to do something big in 1995. That was revealed in January; Bridge of Dreams would be a BBM-sponsored interpromotional event at the Tokyo Dome. While RINGS and Weekly Pro had apparently had a difficult relationship in the past, the promotion was actually the first to finish its contract. More troublesome was the matter of WAR. Gong reported that negotiations had fallen through in their January 26 issue, but what went unmentioned was that the meeting between Yamamoto and WAR president Masatomo Takei had gone south when Yamamoto informed him that, if WAR went ahead with the Korakuen Hall event on the same date that had already been scheduled, BBM would book WAR in the position of a minor promotion. While Weekly Pro and AJPW had had a good relationship for years, their participation was far from assured. Negotiations were conducted between Baba and BBM’s business department head, an unnamed man who had also played on the Yomiuri Giants. While that made him a senior to Baba, business was business, and the situation remained deadlocked until the deal with WAR fell through, since Baba refused to do any business with Tenryu. Once that matter was settled, though, another sticking point was whether NJPW or AJPW would have the main event. NJPW President Seiji Sakaguchi proposed that the match order be decided in order of the ages of each promotion (as determined by the date of their first show), which would give NJPW the nod by seven months. It took a 10 million yen bonus for AJPW for Baba to agree to this compromise, although the final card would not strictly adhere to this (under this logic, after all, AJW would have had the main event). The February 23 issue of Weekly Pro featured the announcement that AJPW would enter; the agreement had been reached on the 17th. Now it was a question of what match the promotion would hold to represent itself. Earlier in the book, Ichinose recalled that he tried to make a dream match happen here: Misawa, Kobashi & Baba vs. Kawada, Taue & Tsuruta. Weekly Pro held a fan vote for the AJPW match at Bridge of Dreams, and this was apparently the legit top result, but it was vetoed by Baba. Ichinose did not know the conditions that had been laid out for Tsuruta’s return to the ring, and begged him to reconsider. Baba was unmoved, and Ichinose was forced to falsify the top result of the poll: a six-man with Stan Hansen & Steve Williams in Baba & Tsuruta’s places. However, Steve Williams’ bust at Narita Airport at the start of the Champion Carnival put an end to this plan, and Baba refused to take his place, which was why Johnny Ace was put in the match that we got. BBM commissioned the construction of the ring to ensure fairness, but it was discovered on the day of the event that they had forgotten the tag ropes. Ichinose himself had to buy some rope at a hardware store and hastily affix it to the turnbuckles under Kyohei Wada’s supervision. This was in line with Ichinose’s other duties with regards to the event, which included a central role in contacting and negotiating with the promotions, arranging the catering, booking hotels for the Michinoku Pro and foreign talent, and securing the rights to entrance music. AJPW’s match has long been considered the highlight of the show. Motoko was very proud of it, and NJPW’s Shinya Hashimoto and Pancrase’s Ryushi Yanagisawa highly praised the match in their own post-show comments. However, Weekly Pro was the only publication to give the event the reportage it warranted. Gong snubbed it entirely, in favor of coverage of the WAR counter-event at Korakuen Hall (remember, the one they had refused to drop in BBM negotiations) which they sponsored. Tokyo Sports wrote a 500-word report the next day with match results, but they offered no mention of BBM nor any photos of the event, instead giving full coverage to the Gong/WAR show. Ichinose then brings up the last segment of the show, in which Tarzan himself entered the ring to cut a promo segment with Hashimoto teasing a potential future show. The crowd did not embrace him, and Ichinose wonders what this meant. “Had he become too big? Were they angry about WAR’s absence? Or was it a warning to people behind the scenes that they should not perform on the microphone like wrestlers?” Ultimately, Ichinose considers the show “the beginning of the end” for the Yamamoto era of Weekly Pro. In fact, all the way back in Part Two, Ichinose skipped ahead to recount an incident in 1995 when Yamamoto revealed the truth to him: Weekly Pro’s circulation was 300,000, but its readership had stalled at the 220-30k range. As for the show being taped but never seeing commercial release, that was apparently a condition on Baba’s part. (Footage of Kintaro Oki's retirement ceremony would be licensed for South Korean television, but I do not know if there were any agreements to give the event domestic news coverage, which had been allowed with Tokyo Sports' Pro Wrestling Dream All-Star Match show sixteen years earlier.)

-

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 22-24, PART TWO [KIKUCHI WINDS DOWN, KAWADA WINS TRIPLE CROWN]

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 22-24, PART TWO Chapter 23 doesn’t offer much insight into AJPW’s product in the second half of 1994, but there’s a bit. It’s arguably more about Ichinose’s experience working for Weekly Pro and under Tarzan Yamamoto, which I am going to save for the next post since that will largely be about Weekly Pro and the Bridge of Dreams show. --- “I know that every time I fight, my body gets more and more tattered, but I can't stop chasing him, and I'm going to keep chasing him. I've been chasing Misawa for 15 years…” Ichinose doesn’t write that much about 6/3/94 itself, besides the story beat of Misawa bringing back the “Tiger Driver something or other” that Kawada had forgotten about to defeat him. He does cover Kawada’s comments in a subsequent interview, though, in which he expressed his wish for another match with Misawa as soon as possible and said that he hoped Steve Williams would not dethrone Misawa. The first match of the following tour, a Korakuen six-man, was most notable for Kawada’s brutalizing of Kikuchi. From here, Ichinose skips ahead on a tangent about Kikuchi that I’m really glad he made. Tsuyoshi Kikuchi spent the last years of his wrestling career working the indie circuit as a “punch-drunk” character, while holding a restaurant job. In 1993, Kikuchi was at a crossroads. The 29-year-old had not been concerned about the tolls of his job before then, but the combination of Jumbo Tsuruta’s absence and Kikuchi’s new girlfriend made him start to think about the future. In February 1995, Kikuchi got married; three months later, he transferred from the Super Generation Army to the Holy Demon Army by his own request. He felt that remaining with Chosedaigun was a danger to his physical well-being and wanted to “run away from that place” to “make his newfound love eternal”. Two years later, he would transfer again to Akuyaku Shokai, the “heel” faction in AJPW's comedic six-mans. Although he had a resurgence with Yoshinobu Kanemaru in early 2000s NOAH, Kikuchi’s career generally wound down from this point. Kikuchi was let go from NOAH in the post-Misawa restructuring and got a job in Sendai in conjunction with freelance bookings. His goal was to become a full-time employee at a food distribution warehouse, which he had almost attained before the warehouse was destroyed by the 2011 tsunami. Kikuchi admits he “almost gave up on life” after that, but he managed to land back on his feet with a distribution job at a drugstore. His boss then hooked him up with the manager of a new yakiniku restaurant; a photograph provided in the book seems to indicate that he had continued to work there at the time this book was composed. Meanwhile, Kikuchi reinvented himself on the indie circuit. Kikuchi does confess that he has some form of CTE (he admits to exhibiting incoherent speech), but states that he plays it up for his bizarre, wig-wearing character. He also expresses confusion that people refer to him as a legend; he had wanted to be “like Keith Richards,” sure, but he stopped being desperate enough. (Two years after this book was published, Kikuchi wrestled a retirement match against Koji Kanemoto.) --- The Summer Action Series tour built up to the match that would see Misawa lose the Triple Crown to Steve Williams. The most Ichinose has to add to it is recalling that Yamamoto asked him who he thought would win, and that he absolutely did not see Williams going over coming. Kobashi would be Williams’ first challenger. Unlike his fellow Shitenno, whose first Triple Crown challenges were held in mid-size venues, Kobashi’s first shot headlined the Budokan. Ichinose covers an interview he did with Kobashi before the tour began, but this segment of the book doesn’t offer any particular insight on the match beyond it being an expression of Kobashi’s ideals as a wrestler. The match would be called “the MVP of the summer” in Tarzan Yamamoto’s catchcopy (Japanese term for slogan), but it would not win the MOTY award. Ichinose jumps off this point to write about the big interpromotional matches of the time, since the WAR/FMW match between Genichiro Tenryu & Ashura Hara and Atsushi Onita & Tarzan Goto was what won the Tokyo Sports award that year. He also remarks on the cover of the last Weekly Pro issue of the year, which he is certain would have featured Misawa & Kawada after their RWTL victory (I think that's all he writes about the tournament) were it not for the bloodied visage of a Yoji Anjo who had just fought Rickson Gracie. If puroresu was going to pursue this further, than AJPW would no longer be able to afford remaining silent on the spectre of MMA. (Ichinose skips ahead to mention Baba's prediction upon Naoya Ogawa's NJPW signing that they would strap the rocket to him, and that it would cause friction with those who had paid their dues in the company culture.) Kawada won the Triple Crown from Williams on October 22 at the Budokan, but the most interesting thing Ichinose writes about the tour is more devoted to Tarzan Yamamoto’s decision to make the cover of the Weekly Pro issue which covered the beginning of the tour feature not a photo from the Kawada vs Williams tag that started the tour, but rather a shot of Satoru Asako elbowing Kawada from a Chosedaigun/Seikigun six-man two days later. The chapter ends with the first tour of 1995. At the urging of the local promoter, Kobashi and Williams had a singles rematch in the Oita Prefectural Gymnasium which went to a thirty-minute draw; this was an example of the burden Kobashi felt to revitalize their product on the provincial circuit through his performances. His second Triple Crown shot was set for the January 19 show at the Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium, two days after the Great Hanshin Earthquake. The show was retooled into a charity event. Kobashi stated before the match that he wanted to put on a match so great that even the people who could not make it to the show would be proud that it was held in Osaka. He & Kawada would put on the first one-hour draw of Heisei puroresu. Ichinose writes that the one-hour match had become “an endangered species” after Jumbo/Choshu, Inoki/Brody, and Inoki/Fujinami had ended the tradition in Showa puroresu. Ichinose recalls that the Weekly Pro match report took up sixteen pages, a then-record, though he does not mention that Tarzan Yamamoto was at the commentary table for this match.)

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

I've seen Sakaguchi use a jumping knee as a finish in 1977, which makes me wonder whether he or Jumbo was first to borrow that attack (which Jumbo got from kickboxer Tadashi Sawamura). I know Jumbo was using it as early as the 5/1/76 Champion Carnival match against Baba, but I haven't seen any 76 Sakaguchi to compare.

-

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 22-24, PART ONE [EARLY 1994 - TAKAO OMORI, MISAWA/KOBASHI VS BABA/HANSEN, UWFi TOURNAMENT, CHAMPION CARNIVAL, TIMESLOT CUT]

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 22-24, PART ONE I have completed the second half of part three of The Rainbow over the Night, which covers the sixteen months from the start of 1994 through the 1995 Champion Carnival and concurrent Bridge of Dreams Tokyo Dome show held by Weekly Pro Wrestling, albeit through the discursive approach that has become characteristic of this book. This stretch hasn’t been as revealing as what came before, and much of the next two chapters are more about Weekly Pro than AJPW, but I can squeeze some stuff out of it. First, though, I have been getting the author’s name wrong this whole time: he’s Hidetoshi Ichinose, not Ichise. I will go back and correct earlier posts. This covers the notable material from chapter 22. ---- TAKAO OMORI AND THE 1994 ASUNARO CUP Each 1990s iteration of the NYGS thus far had had a special gimmick: the Kobashi, Taue, and Akiyama trial series of 1990, 1991, and 1993, and the novel tag title contendership tournament of 1992. 1994 would continue this trend with the revived Asunaro Cup. Ichinose brings this up to segue into the topic of Takao Omori, who “made his blood run hot” at the afterparty of the first AJPW show of the year when he stated his intent to perform well in the tournament and get a good writeup in Weekly Pro. Omori was born in 1969, and got into wrestling through the Tiger Mask boom while in the sixth grade. Influenced by his older brother, Omori followed both AJPW and NJPW and became a “maniacal fan”. He recalls wrestling with his friends in junior high and practicing dropkicks in the concrete-floored hallways of his school. Omori entered the high school judo club, but decided to pursue gridiron football during his university years, as he wanted to enjoy campus life to an extent that he wouldn’t if he joined an athletic club, but figured that football was similar enough to pro wrestling. He played as a defensive end. During his junior year, the discussion of employment began amongst his peers.1 The bubble economy was in its twilight, but it was still a seller’s market for the students. Omori was uncomfortable at how his classmates flocked to companies based on salary and name recognition, but he wanted to find a job to reassure his family. It was then that he saw an All Japan recruitment notice in an issue of Weekly Pro. AJPW and NJPW were the only options Omori considered (no UWF), so he sent an application. It was accepted, and Omori was invited to a Korakuen show in March 1991 to meet Baba. Omori was prepared to drop out in order to join immediately, but Baba discouraged this, as he wanted Omori to have an education to fall back on if his wrestling career failed. Omori would earn his degree, but would also gain a head start on wrestling conditioning. After leaving the football team, he enrolled in Animal Hamaguchi’s wrestling school for the last three months of his senior year. The dojo held classes on Satudays, taught by Shoichi Funaki (yes, *that* Funaki), but he would also spar with Hamaguchi and 20 to 30 other students. One of those was Shinjiro Ōtani, who had entered the school six months before Omori; it’s because of this that Omori still refers to him with the “san” honorific despite being three years his senior. Omori took the entrance exam in March 1992, one month after Akiyama announced his signing with AJPW. There had been 40-50 other people who had visited that 1991 Korakuen show after submitting their applications, but Omori recalls that every single one who went through with it alongside it ran away during their first night. His tenure at the Hamaguchi Gym had done little to prepare him for the demands of the training regiment, to say nothing of the culture shock of starting from the bottom of this hierarchy and performing chores, but Omori persisted. According to Kawada, by this time Baba had actually softened the training regimen to encourage trainees to stick with it; Ichinose writes that “it is easy to infer” that Baba had reformed the disciplinary component and the bullying which often arose. Nevertheless, the life of a trainee had been too much for many. Plans to debut Omori alongside Akiyama at the 25th Anniversary Korakuen show on September 17, 1992 were scrapped for a conventional debut match on October 16, against fellow young wrestler Satoru Asako. In just his second tour, though, Omori would have his first match against a gaikokujin (a loss to Billy Black on November 29). The following year, Omori notched his first wins against Kurt Beyer (three in the New Year Giant Series tour), and even got fed to Danny Spivey in the first show of his fourth tour. Omori would “graduate” from the undercard in 1993, but this accelerated path produced a talent which had not matured. This was starkly shown in a singles match against Kawada on the second night of the 1993 Fan Appreciation Day event on September 23, in which Omori recalled that Kawada “rolled him around in the palm of his hand”. Omori was hungry to prove himself in the Asunaro Cup, and his stating such at the 1994 kickoff show’s afterparty lit a fire under Ichinose. The revived tournament would be a round-robin (with a final) between the seven wrestlers who had debuted from 1989-1992: Akiyama, Asako, Tamon Honda, Ryukaza Izumida, Masao Inoue, Omori, and Richard Slinger. Omori placed second with eight points to Akiyama’s twelve, and so the two wrestled the final on January 29 in Korakuen, 22 days after having their first tournament match against each other in Kochi. Ichinose writes that, while Omori was defeated, the content of the match was different than the Kawada match had been, as Omori had demonstrated and conveyed his “awareness” of Akiyama. He was rewarded by chants of his name amongst the Korakuen crowd. Unfortunately, Omori was not so well received by Weekly Pro, as Masayuki Sato’s match report was critical and did not acknowledge Omori’s warm reception. Omori was also criticized by his peers, which by his own admission led him to develop a certain stubbornness. One example of this was his Baba-angering refusal to wear navel-covering long tights. Ichinose writes that it took a while for Omori to sublimate this character trait into his style of wrestling, and that if he had then he would have fulfilled expectations earlier. A DREAM MATCH AND A DREAM TOURNAMENT 1994 saw AJPW increase its annual number of Budokan shows from six to seven, which meant that every tour except the first held a card in the venue. It was a testament to the prosperity of the promotion in the early 90s, particularly in the Tokyo market, but Ichinose writes that “there is no doubt” that this decision only increased the burden that the Four Pillars were forced to bear, what with the losses of main-eventers Terry Gordy and Jumbo Tsuruta and the lack of a new force to take their place. The new Budokan show was the last show of the Excite Series, on March 5. Notably, this would see Akiyama & Omori team up against the Holy Demon Army in the antepenultimate match, but the “dream match” that made the show a sellout was a Misawa/Kobashi vs. Baba/Hansen rematch. Although he had figured in some NYGS main events that played off of it, Baba had hesitated to run this match again, as it had only happened in the first place when he filled in for Ted DiBiase. He acquiesced due to fan demand, and planted seeds with “mischevious” comments to reporters at the January 9 show. At the “secret saloon” meeting with Ichinose, however, Baba angrily shot down the reporter’s suggestion to put the tag titles on the line and have Baba win. He considered it an insult to the belts and to himself, as he had intended for his (untelevised) 1989 shot at the tag titles alongside Rusher Kimura against the Olympians to be his last main-event title match. (According to the February 14 Observer, it was stipulated that if Baba & Hansen won this match, they would earn a title shot.) Something interesting happened before the tour was set to begin. On February 15, UWF International held a press conference inviting five wrestlers to a Pro Wrestling World Tournament for the prize of 100 million yen. The five were Masakatsu Funaki, Shinya Hashimoto, Akira Maeda, Mitsuharu Misawa, and Genichiro Tenryu. Obviously this was never, ever going to happen, but I think it’s worth covering the fallout from this conference straight for the historical record. Four days later, Misawa was surrounded by reporters at the start-of-the-tour Korakuen show, to whom he said he had already received the invite. "In a word, it's a moot point. Even if a billion dollars or ten billion dollars were raised, what I’ve done for 13 years in All-Japan would fall apart if I participated. So how can a Mitsubishi employee work part-time at Mitsubishi? If you really wanted to make a reasonable proposal, you would have sent it to the president, not me. I'm Mitsuharu Misawa, a professional wrestler, but I'm also Misawa of All Japan. Takada is trying hard to get pro-wrestling recognized as a sport, isn't he? If you do this, people will think that wrestling is like that again. The fans may say they want to see it, but this is my answer... I wonder if UWF International wrote to me thinking I'd actually appear.” Ichinose doesn’t say whether any of the other invitees called UWFi’s bluff so frankly, but all five declined the invitation by the March 10 deadline. The following day, UWFi director Yukimitsu Kando held another press conference, in which he remarked it was a pity that Misawa had not responded as a champion, but “in the manner of a businessman or civil servant”. Shigeo Miyato echoed this, saying something to the effect of “I don't think it's right for people who are usually covered in blood from fighting outside the ring or hitting each other with a chair to follow the rules of society only on such occasions.” Ichinose writes that this betrayed Miyato’s fundamental ignorance of what All Japan had become and revealed that they never could have gotten on the same page. The tournament never happened, and while RINGS did propose an interpromotional match, that never bore fruit either. Misawa’s comments made AJPW’s isolationist policy clear, and the possibility that they would participate in the Super J-Cup which actually did happen that April was a moot point. CARNIVAL AND THE TIMESLOT CUT Ichinose does not mention the story surrounding the 1994 Champion Carnival that has since widely circulated in Western circles: that is, that Misawa’s neck injury at the hands of Doug Furnas on March 21 was a work to write him out of the tournament, or at the very least exaggerated. In the section before he covers the Misawa/Furnas match—but after he ends the previous section by mentioning Misawa’s “unfortunate accident”—Ichinose happens to write about “the etiquette of an All Japan reporter”, as well as his his conservative approach to covering matches that become shoots (such as Maeda vs Andre and Jackie Sato vs Shinobu Kandori). He recollects an incident when, early in his career, he used “babyface” and “heel” in an interview with All Japan, only for Baba to ask what those terms meant. It could be interpreted as an implied admission for those in the know that something *did* happen, but that Ichinose does not wish to break kayfabe. As revelatory as his book has been, as far back as he has peeled the curtain, Ichinose is fundamentally an Apterist writer. Needless to say, he makes no mention of the claim (printed in the April 11 Observer) that Kawada had been booked to pin Misawa for the first time in a tournament match. It was while the tournament was underway that the AJPW Relay television program was cut from an hour to thirty minutes, with the broadcast rights fee likewise slashed. The contemporaneous Observers made frequent note of the program’s ratings decline over the previous two years (while acknowledging that its viewership share was excellent considering its late-night timeslot), but Ichinose states that this was tied to an overall viewership decline for the network. The beginning of the Lost Decade had reduced the network’s sponsors, and the network’s most lucrative program, the Yomiuri Giants’ baseball games, had been hit hard. Executives considered cutting AJPW entirely, but according to the March 21 Observer, the promotion was eventually given the choice between a half-hour weekly show or a one-hour biweekly show. The change took effect for the April 2 episode. A couple housekeeping notes on the Champion Carnival to close out this post. Kawada defeated Williams in the final match, which was the first Carnival final to be held in the Budokan. Despite going head-to-head with the Super J-Cup final in the Ryogoku Kokugikan, AJPW continued their Tokyo sellout streak. Six days earlier, Kobashi got his first pinfall over Hansen in a tournament match.

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

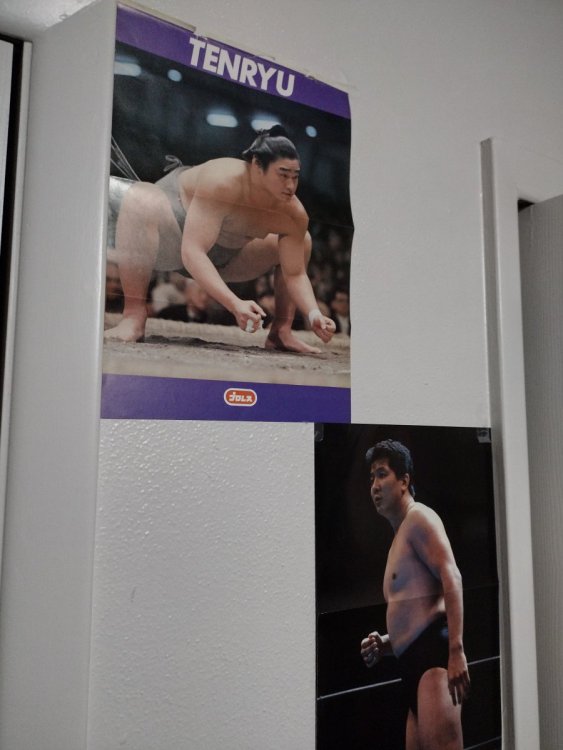

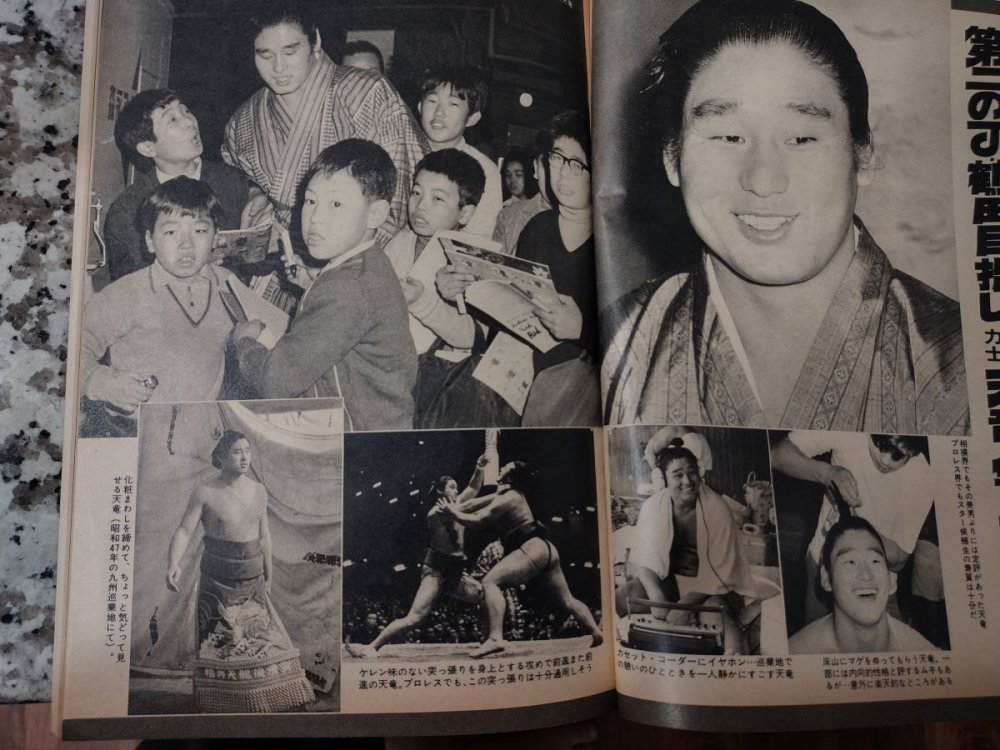

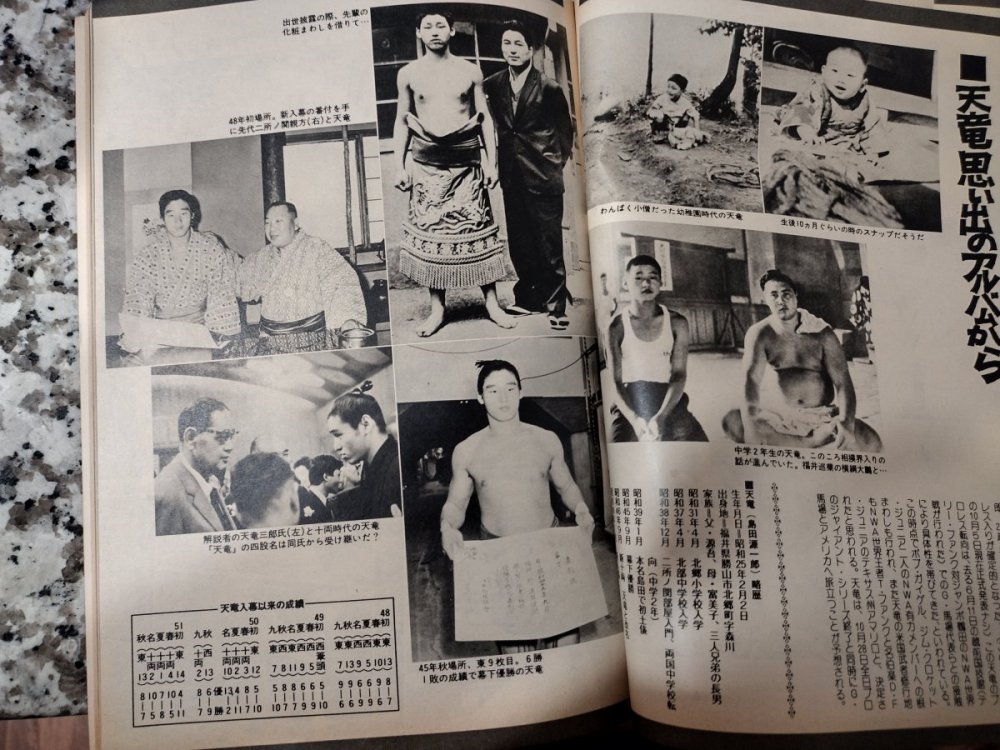

Some coverage of an AJPW sumo signing from an issue of Monthly Pro Wrestling released 45 years ago to the month, as well as an included pinup. I don't think the guy ever amounted to much, though.

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

Fuck that, Hayato deserves better from me. I just took to my history thread to post an expanded version of an obit I threw together on Monday for Reddit and a couple Facebook groups.

-

PURORESU OBITUARIES: MACH HAYATO (1951-2021)